By Brandon Moseley

Alabama Political Reporter

1965 in Alabama was a very different place. Whites used a complex system of poll taxes, literacy tests, threats, and sometimes actual violence to keep the Black minority from exercising their right to vote. The state legislature of the day was literally all White. Whites even represented majority black counties such as Dallas, Lowndes, Macon, and Greene Counties because the vast majority of Black Alabamians were disenfranchised by the segregation of the day.

Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement brought attention to the situation. Violent reactions from pro-segregationists that included bombings, fire hoses, beatings, arrests, and even some murders shocked the nation and over the objections of Southern legislative delegations, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Voting Rights Act outlawed the literacy test and the poll tax and guaranteed that the federal government would be the enforcer of citizens voting rights. Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act gave the U.S. Justice Department preclearance authority over all redistricting done in the southern states. Whether a congressional district, a state legislative district, a county commission district, or even a city council district the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division has to approve that redistricting map.

1965 was a very long time ago. Generations of Alabamians, including this reporter, were not even born then and have no memory of segregation; but still the federal government has to accept any redistricting in a southern state. Since 1965 it has become increasingly common for Blacks and Whites to actually live in the same neighborhoods. This has made the drawing of majority minority districts much more difficult.

To create a majority Black Congressional District (the Seventh) for example the Alabama legislature had to carve Birmingham, Fairfield, and Bessemer out of Jefferson County, take in a portion of Tuscaloosa County, include the rural Black Belt counties of Sumter, Greene, Dallas, Perry, Lowndes, a portion of Clarke, and carve out majority black areas of Montgomery into the same district. It has gotten even more difficult to draw a city council map without losing a minority majority district. The City of Calera recently ran into this problem due to rapid growth. New subdivisions were largely integrated so creating a majority black district often meant house by house drawing of the district. The city passed one redistricting map showing no majority minority district; but that was rejected by the Department of Justice (DOJ) leading to a lengthy court battle. The DOJ said that Calera should not have annexed new subdivisions without getting clearance from DOJ. Calera and Shelby County contend that times have changed and Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act has outlived its usefulness and has no relevance to modern day life.

Former State Senator Bradley Byrne (R) said on Facebook, “Alabama is a far different place than it was in 1965 and I’m proud of that. We have more African American public officials in Alabama than any state other than Mississippi and that’s a good thing for everyone. My daughter Laura Byrne and her generation have grown up without Jim Crow and see leaders of different backgrounds all around and it’s what is in their hearts that makes the biggest difference. No law can improve on that.”

Alabama Attorney General Luther Strange (R) said, “The children of today’s Alabama are not racist, and neither is their government. Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act applies only in a few states. It requires only some states to get permission from federal bureaucrats before making changes to their voting laws.”

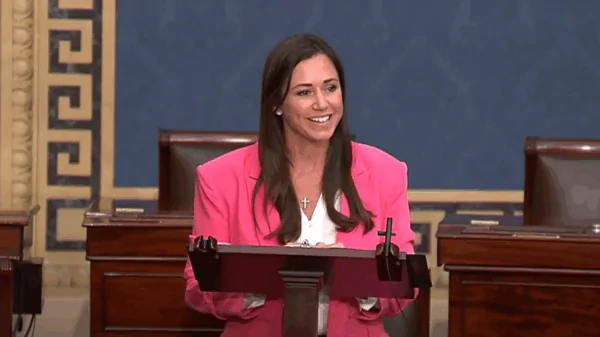

Not everyone agrees. Congresswoman Terri Sewell (D) from Selma said, “I am deeply concerned about the erosion of voting rights that sadly still exist in our state and in this nation. This case, which originates from Shelby County, Alabama, will determine the fate of certain provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 which was passed as result of the Selma to Montgomery march. Ironically, the state that was the impetus for this legislation now threatens the very protections that law affords.

Rep. Sewell said, “No right is more fundamental than our right to vote and the Voting Rights Act still remains the single most important legislation that ensures it. Now more than ever, the legal protections that ensure the participation of minorities are under attack. With state voter identification laws, discriminatory redistricting practices, and efforts to limit voting hours, there still exists a need to prevent voter disenfranchisement and suppression. Prior to the 2012 presidential election, over 180 restrictive bills were introduced in state legislatures across the country signifying the overwhelming need for federal oversight. Congress acknowledged this unfortunate but ongoing necessity when it overwhelmingly reauthorized the Voting Rights Act in 2006 after more than 21 hearings and over 15,000 pages of supporting evidence. It is my hope that the Supreme Court will examine all the facts, apply the law, and rule in favor of ensuring that all Americans can vote without intimidation, prejudice or discrimination.”

Whether the Supreme Court overturns Section 5 or not it is very likely that future Alabama governments will continue to have a difficult time drawing future majority minority districts as young first time home buyers care less and less about what color the people on their street are.