By Stephen Stetson

Executions have been on hold in Alabama since 2013 amid litigation about lethal injection and the chemicals used to kill. Next year, a federal judge will hear two challenges to Alabama’s lethal injection protocol. No matter what the judge decides, the question is not whether Alabama will start executing people again, but how and when.

Plaintiffs in both cases were required to propose feasible alternatives that could be used if the lethal injection protocol is ruled unconstitutional. While we wait for the court’s decision, we ought to reconsider the legal process sending capital offenders to death row, and whether that journey reflects the values of Alabamians – including those who support capital punishment.

Among death penalty states, Alabama is one of only three allowing trial judges to disregard a jury’s recommended sentence of life without parole. We’re also the only state with no guidelines on how judges make decisions to “override” a jury recommendation.

It’s rare for judges to use this power to spare a life. Instead, the overwhelming majority of overrides are used to sentence someone to death after a jury recommends life imprisonment. It takes at least three jurors to block a death sentence recommendation in Alabama – but only one judge to cancel their vote.

Of the states allowing this practice, Alabama is the only one where judges are selected in partisan elections. Nearly a third of death sentences handed down in 2008, an election year, were the result of judicial overrides, according to the Equal Justice Initiative.

Judicial overrides land disproportionately heavily on black defendants. Six percent of Alabama murders are committed by black offenders against white victims, but 31 percent of override cases involve black defendants and white victims.

Defendants facing execution can lack qualified counsel at all stages of the process, starting at trial. To qualify for appointment on an Alabama death penalty case, an attorney needs only five years of experience in any type of criminal case. The state provides no additional training, and until recently, it capped attorney fees at absurdly low rates.

Alabama’s policies surrounding capital defense can have devastating consequences. In one case, the client’s lawyer never told the judge that an expert had opined, before trial, that the victim died of natural causes. As the lawyer later testified, he kept this potentially life-saving development to himself because he was not authorized to hire the expert and was “concerned with receiving the trial judge’s anger by asking for more money and/or a continuance.”

Even when legal representation is demonstrably shoddy, death row inmates often are denied opportunities to have their cases meaningfully reviewed. Numerous examples exist of lawyers missing key deadlines to file paperwork or failing to pay critical filing fees.

In one case, the lawyer for a client with an intellectual disability abandoned him during an appeal without filing a formal notice or even telling the client. More than a year after the filing deadline had passed, the state notified the inmate that it would pursue an execution date. The inmate, whose death sentence was imposed via judicial override, could not even read the notification letter.

As we await a federal decision about the constitutionality of Alabama’s execution protocol, we also must examine the process by which inmates land in the death chamber. Our state fails to guarantee that people accused of capital crimes have well-qualified counsel at capital murder trials, or any counsel for state post-conviction appeals. We allow elected judges to ignore recommended jury sentences in capital cases for any reason. And our system is plagued by unconscionable racial disparities.

These are not Alabama values. Those who truly value all life should demand sensible reforms of our state’s capital punishment system. Ending Alabama’s judicial override policy would be a good start.

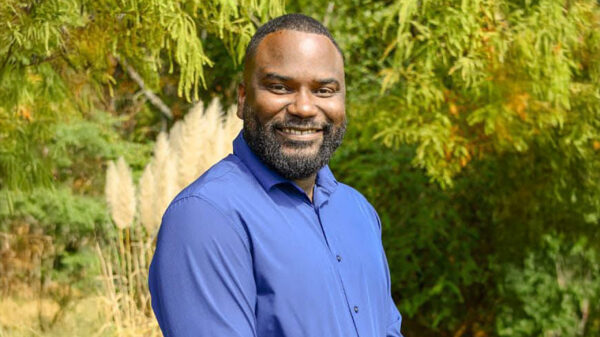

Stephen Stetson is a policy analyst for Arise Citizens’ Policy Project, a nonprofit, nonpartisan coalition of 150 congregations and organizations promoting public policies to improve the lives of low-income Alabamians. Email: [email protected].