It took Marquis Forge five years and 18 banks before he and his partner were able to open their company, Eleven86 Water, in Autauga County, just north of the Black Belt, and a report released Tuesday shows how Black Belt counties lag behind others in economic prospects and investments in businesses.

Forge, a former University of Alabama football player, told reporters during a briefing Monday that he considers Autauga County, which borders the Black Belt’s Lowndes County, part of the Black Belt, and said it shouldn’t have been so difficult to access the capital needed to start a business.

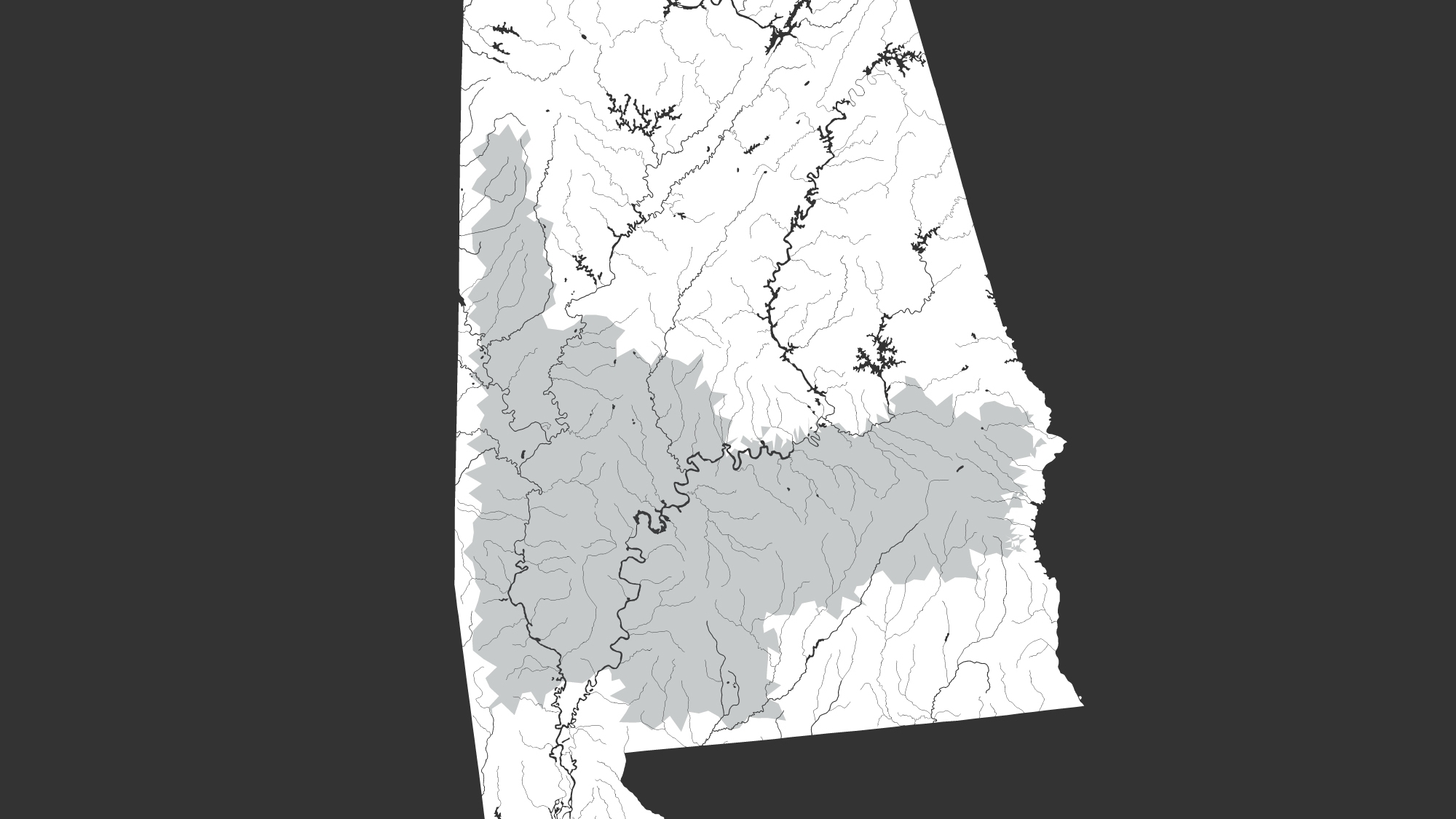

The report released Tuesday by the University of Alabama’s Education Policy Center titled “Black Belt manufacturing and Economic Prospects” is the last in the center’s Black Belt 2020 series, and found that only four of the state’s 24 Black Belt counties, as defined by the center, are above the statewide average of 22.4 businesses per 1,000 residents, and just one, Montgomery County, was above the 2018 statewide average of personal income of $43,229.

Researchers also found that just three Black Belt counties are above the state’s average in gross domestic product being produced by counties of $45,348.

“To achieve Governor Ivey’s ambitious goal of 500,000 a million more Alabama workers with skills by 2025, all hands have to be ‘on deck.’ It will require higher labor force participation rates, particularly in the Black Belt, where the average is 20 points below the statewide average,” said Stephen Katsinas, director of the university’s Education Policy Center and one of the authors of the report.

“Due to smaller economies of scale, our approaches to education, workforce development, and community building will have to be different to reach Alabama’s Black Belt,” Katsinas continued. “In the longer term, we first must define the Black Belt, because you can’t measure what you can’t define. Then we must do what West Alabama Works is doing–go where the people are to bring hope by connecting them to a well-aligned lifelong learning system that makes work pay.”

Donny Jones, COO of Chamber of Commerce West Alabama and Executive Director of West AlabamaWorks, told reporters Monday that one of the keys to helping the Black Belt will be helping state and Congressional legislators understand the nuances of rural Alabama.

Jones said the state should look at how colleges are graded, and that many smaller colleges don’t get credit for putting students through programs that get them short-term certificates that lead to jobs.

“Those are some of the things on the statewide level that we can really start to work on,” Jones said, adding that they’ve already begun teaching modern manufacturing in Black Belt high schools that gives students college credits toward an associates degree while still in high school.

“I think that’s very important for individuals to understand the impact that we can have in our higher ed and our K-12 system, really works hand in glove to move the needle for workforce development,” Jones said.

Jim Purcell, State Higher Education executive officer of the Alabama Commission on Higher Education, told reporters that it’s also important to look at one’s own community and identifying what is “unique and special,” and said he was recently in Autauga County, where he is from, and bought two cases of Eleven86 Water because he remembered how good the water there was.

“I think that’s what you’ve done, is you’ve taken the gift that Autauga’s environment has and enhanced it, so that the people can benefit from it,” Purcell said to Forge. “I think that’s the key.”

Asked what he’d tell state legislators to spur them to make changes so that other entrepreneurs wouldn’t have to struggle as hard as he did to open a business, Forge said he would ask for a clearer path for assistance.

“Instead of digging down through a tunnel with a spoon I would have someone outline the tracks on getting funds and assistance from local, state and the national level, because there are funds out there,” Forge said.

After going to 18 banks to get the financing he needed, he still had to liquify all his assets to make it happen, Forge said.

“How many people are going to do that?” he asked. “We shouldn’t have to do that.”

To read all of the Education Policy Center’s reports on Alabama’s Black Belt, visit here.