Twenty-six-year-old white Episcopal seminary student, Jonathan Daniels knew the dangers he faced.

His cleric’s collar and the quarter-sized black and white lapel pin that he always wore — with the white cross in the middle and the initials “ESCRU” underneath, which stood for Episcopal Society for Cultural and Racial Unity — made him a target of the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists.

He answered the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s call on March 7, 1965, for clergy from the North to come to Selma after Bloody Sunday. That same day, Daniels boarded a chartered plane to Atlanta.

“Jon knew in his heart that it was naturally the right thing to help those who needed it,” said Daniels’ childhood friend, Bob Perry, who lived around the corner and attended kindergarten through high school with him in Keene, New Hampshire.

Daniels marched in the Selma marches.

Klan members were targeting white clergy and northerners who’d come to Selma to march, including Reverend Jim Reeb and Viola Liuzzo, who were murdered for their participation. Most northern clergy went home after that.

But Daniels stayed, spending his final days in Alabama.

From interviews with friends of Daniels and legal experts, a review of news coverage at the time, and reading the trial transcripts, even in death, Daniels faced injustice in Alabama.

His death, though, would impact Alabama’s legal system in ways he could have never envisioned.

An alleged Klan member and Daniels’ death

Nearly five months after the Selma marches, Daniels participated in another protest on Saturday, Aug. 14, 1965, in Fort Deposit with Student Nonviolent Coordinating Council leader Stokely Carmichael and more than two dozen other activists.

The demonstrators picketed local stores that refused to serve Black Americans.

Lowndes County sheriff’s deputies arrested Daniels and other demonstrators and took them to the Hayneville jail where they stayed for six days.

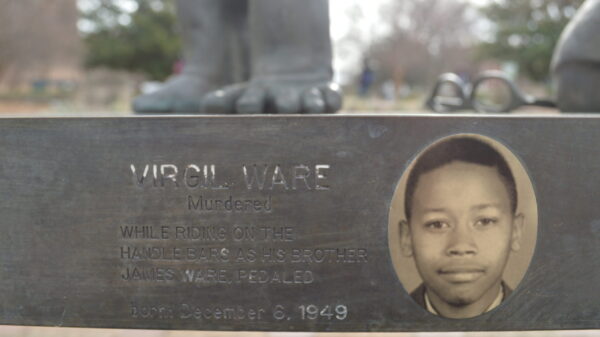

Six days later, on Aug. 20, 1965, after being released from the Hayneville jail, Daniels walked with 17-year-old Tuskegee University student Ruby Sales and teenager Joyce Bailey — who were both Black — along with white Catholic priest Richard Morrisroe to nearby Varner’s Cash Store to purchase soft drinks.

Thomas L. Coleman, 55, a white highway engineer, part-time sheriffs’ deputy and an alleged member of the Ku Klux Klan, confronted the group holding a shotgun.

“This store is closed. If you don’t get the hell off this property,” Coleman said, according to Sales, “I’m going to blow your brains out.”

When Coleman pointed the shotgun at Sales, Daniels’ lifetime of sticking up for other people and his four years of training at the Virginia Military Institute burst into action.

Within seconds, Daniels grabbed the bottom of the back of Sales’ shirt and pulled her to his left and out of range of Coleman’s shotgun. Coleman shot Daniels in the chest at point-blank range.

Daniels fell backward. He died moments later.

Coleman then aimed his gun at Morrisroe who had grabbed Joyce Bailey’s hand and was running away from the store.

Coleman shot Morrisroe in the back. Though severely injured, Morrisroe would survive the shooting.

“I saw the best of and the worst of white men in the same moment,” Sales said in a 2019 Ted Talk.

The shooting of these two civil rights workers made headlines across the country. President Lyndon Baines Johnson ordered the FBI to investigate.

“One of the most heroic Christian deeds of which I have heard in my entire ministry and career for civil rights was performed by Jonathan Daniels,” said the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King at the time.

Five hours after the shooting, sheriff’s deputies arrested Coleman. They took him to the Hayneville jail, the same jail that they’d released Daniels from earlier that day.

The arrest log shows that the sheriff’s department booked Coleman into jail and charged him with murder.

Coleman’s brother-in-law paid his bail and sheriff’s deputies released Coleman that same day.

Jury members standing outside the Lowndes County courthouse in Hayneville, Alabama, during the trial of Thomas L. Coleman.

Photo by Jim Peppler. Courtesy Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Coleman’s Trial

Six weeks after Daniels’ death, a grand jury met on Sept. 22, 1965. The grand jury reduced the charge from first-degree murder and indicted Coleman with manslaughter.

Then-Alabama Attorney General Richmond Flowers told news reporters that he was unhappy that the grand jury reduced Coleman’s charge to manslaughter.

Flowers said the prosecutors assigned to the case, Lowndes County Solicitors Carlton Perdue and Arthur Gamble, should not have sought an indictment for Coleman without the testimony of Father Richard Morrisroe, who was still at the hospital recovering from his wounds.

Exercising his legal authority, Flowers removed Perdue and Gamble from the case and put his best criminal investigator, Joe Gantt, in charge of the prosecution team.

“The Attorney General must have felt some concerns about whether that prosecutor could fairly try the case for the state,” said John England, a former judge and professor of law at the University of Alabama.

Less than a week later, on Tuesday, Sept. 28, the trial started at the Lowndes County Courthouse on South Washington Street in the heart of downtown Hayneville. The Greek-revival style building, built in 1856, was one of a few historic buildings from that era still in use in Alabama.

As the trial started, Black Americans and whites could be seen sitting in different sections of the courtroom. Judge Thomas Thagard maintained a segregated courtroom despite the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which declared segregation illegal.

At the defendant’s table, Coleman sat with his attorneys, his nephew Robert Coleman Black and state Sen. Vaughan Hill Robison.

Coleman had a history of violence but had never been brought before the court for it. Six years earlier, he’d shot and killed an incarcerated Black man who was working as a prison laborer cleaning up a highway.

Gantt made the first move by requesting Thagard delay the trial to give time to hear the testimony of Morrisroe, who was still in the hospital in serious condition.

Thagard denied the request.

Such a denial was “highly unusual,” according to England. All else being equal, he questioned whether the trial could be fair given that decision to deny the request.

Gantt then requested nolle prosequi, which, if granted, would have meant that the state would no longer prosecute the case — at least for a time. That request would have allowed Coleman to go free, but it would have also prevented Coleman from being acquitted. Protecting prosecutors from the danger of double jeopardy had Coleman been acquitted, it would have allowed the state to try Coleman at a later date.

Thagard refused to grant Gantt his request, a move that would be very unusual today, according to Brandon Falls, an attorney at Campbell Law Firm and former Jefferson County district attorney.

In a surprising move, Thagard removed Gantt and reinstated the local prosecutors, Perdue and Gamble. Such a move would be unheard of today.

“The judge exceeded his authority,” said Falls. “He had no power to appoint the prosecutors in the case.”

Then Thagard ordered the trial to start. Coleman’s lawyers entered a plea of not guilty.

In less than an hour, defense lawyers called 14 witnesses. Three of the witnesses stated that Daniels was carrying a knife and that Morrisroe had a gun when they approached the store.

The prosecution — no longer the prosecutor chosen by the state attorney general but rather the local prosecutors who showed no particular interest in securing a guilty verdict — called their witnesses.

In another violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Thagard made the Black prosecution witnesses who’d seen the shooting — Ruby Sales, Joyce Bailey, Jimmy Rogers, Gloria Larry, and Willie Vaughn — stand outside until they were called to testify, unlike the white witnesses who were sitting in the courthouse.

Sales testified that Coleman shot Daniels. She was the only prosecution witness to say that in court testimony. Bailey and Sales said that neither Daniels nor Morrisroe had a weapon.

But at times it was hard to distinguish “the prosecution’s” case from the defense’s case.

Prosecutors Perdue and Gamble called Leon Crocket, who’d been playing dominoes with Coleman at the courthouse moments before the shooting.

Crocket testified that Daniels had a knife and Morrisroe had a gun. He served as the court bailiff and was working as the bailiff before and after his trial testimony.

“That alone would have been the basis for a change of venue request,” England said. The prosecutors’ concluding arguments to the jury sounded like remarks made earlier by the defense attorneys. Not only were the arguments incongruous with the testimony of the prosecution’s witnesses, they seemed to undermine them. In Perdue’s concluding arguments to the jury, he told the jury that Varner had called Coleman for help even though she’d testified that she had not called Coleman.

Even though the Black American youths who had been with Daniels at the store said that Daniels did not have a knife, Gamble referred to “that knife” in his concluding argument to the jury. No knife or gun alleged to be held by Daniels and Morrisroe just before the shooting was ever produced as evidence at the trial.

All the while, members of the KKK sat in the audience. During the two-and-a-half-day trial, Ku Klux Klan members Eugene Thomas, William Eaton and Collie LeRoy Wilkins — accused of killing a 39-year-old white mother of five, Viola Liuzzo, after the Selma marches — attended the trial, according to a photograph by United Press International.

“It’s pretty obvious that they would have had an impact,” England said.

It would have signaled to the jury that in that community, the jury should acquit another white man, England said.

As the jurors left the courtroom, one of them winked as he walked by Coleman, according to news reports at the time. Jurors then walked to the court clerk’s office where Leon Crocket — the bailiff and the man who had testified at the trial earlier for the prosecution but in support of the self-defense claim of the defendant — gave $24 to each of them for their daily jury pay.

All-white, all-male jury acquitted Coleman

After the two-day trial, at mid-morning on a crisp 70-degree day at the Hayneville courthouse on Thursday, Sept. 30, 1965, Lowndes County jury clerk Kelly Coleman, cousin of defendant Thomas L. Coleman, who had selected the jurors from the jury pool, read the verdict, “Not guilty” to the packed courtroom.

The judge adjourned the court minutes later.

The all-male, all-white jury rose from their seats to leave the courthouse.

At least one juror walked over to the table where Coleman was seated and shook his hand, according to news reports. Coleman, who could never be prosecuted again for killing Jonathan Daniels, left the courthouse a free man. Coleman remained under indictment on an assault and battery charge for shooting Morrisroe where he could be subjected to six months in jail or a fine of up to $100.

After the trial, Coleman continued to live in Hayneville. The charge for injuring Morrisroe was never prosecuted. Coleman died on June 13, 1997.

On the same day as Coleman’s acquittal in a different courtroom, federal Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. made a decision that seemed almost irrelevant given the day’s events.

Johnson cleared the Aug. 14 demonstrators including Daniels and Morrisroe of all charges. He stated that their arrest for picketing without a permit in Haynesville was unconstitutional.

Swift reaction to the acquittal

Newspapers across the country covered the acquittal on the front page of the papers later that day and the following day.

“Appalling,” said Alabama Attorney General Flowers to news outlets about the verdict.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) asked Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black to cease trials in Lowndes County until Black Americans and women could serve on juries.

Five days after the shooting, civil rights organizations and faith leaders issued a statement charging that white supremacists in the South now had a “white license to kill.”

On the same day, the ACLU and ESCRU filed a lawsuit, White vs. Crook, to call on officials to end the practice of barring Black Americans from serving on juries in Alabama.

The following week, local news outlets reported that 50 Tuskegee University students were marching through downtown Tuskegee, carrying a casket draped in black labeled “Alabama Justice” and singing the song “We Shall Overcome.”

“It was as egregious as other cases at the time,” says long-time Alabama journalist John Fleming, who has reported on civil rights-era cases for decades.

Daniels’ legacy

Since his death, Daniels has received recognition for his act of heroism in many places, including his hometown of Keene, New Hampshire; his alma mater Virginia Military Institute (VMI); and the Episcopal Diocese of Alabama, among others.

“Jonathan showed a level of unbelievable courage,” says Daniels’ classmate at the Virginia Military Institute Wyatt Durrette Jr.

“Jonathan exemplifies the best of VMI and reflects what that type of courage should mean,” he said.

Daniels’ impact on the criminal legal system in Alabama and throughout the South is less well known.

A year after Daniels’ death, in response to the ACLU and ESCRU lawsuit, Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr.ordered the inclusion of Black Americans on jury pools and also struck down the exclusion of women.

“The whole jury system after Jonathan’s death came under attack in affirmative lawsuits, literally scores of them all across the South, to result in ordering jury officials to put Blacks in the jury box so that they could be selected at random with whites for juries,” said ACLU attorney Charles Morgan in the 1999 film, Here Am I Send Me: The Journey of Jonathan Daniels, that aired on PBS and was produced by former Keene State College Emeritus Professor Dr. Larry Benaquist and retired professor Bill Sullivan.

“That resulted in a great power shift that’s gone generally unnoticed,” Morgan said.