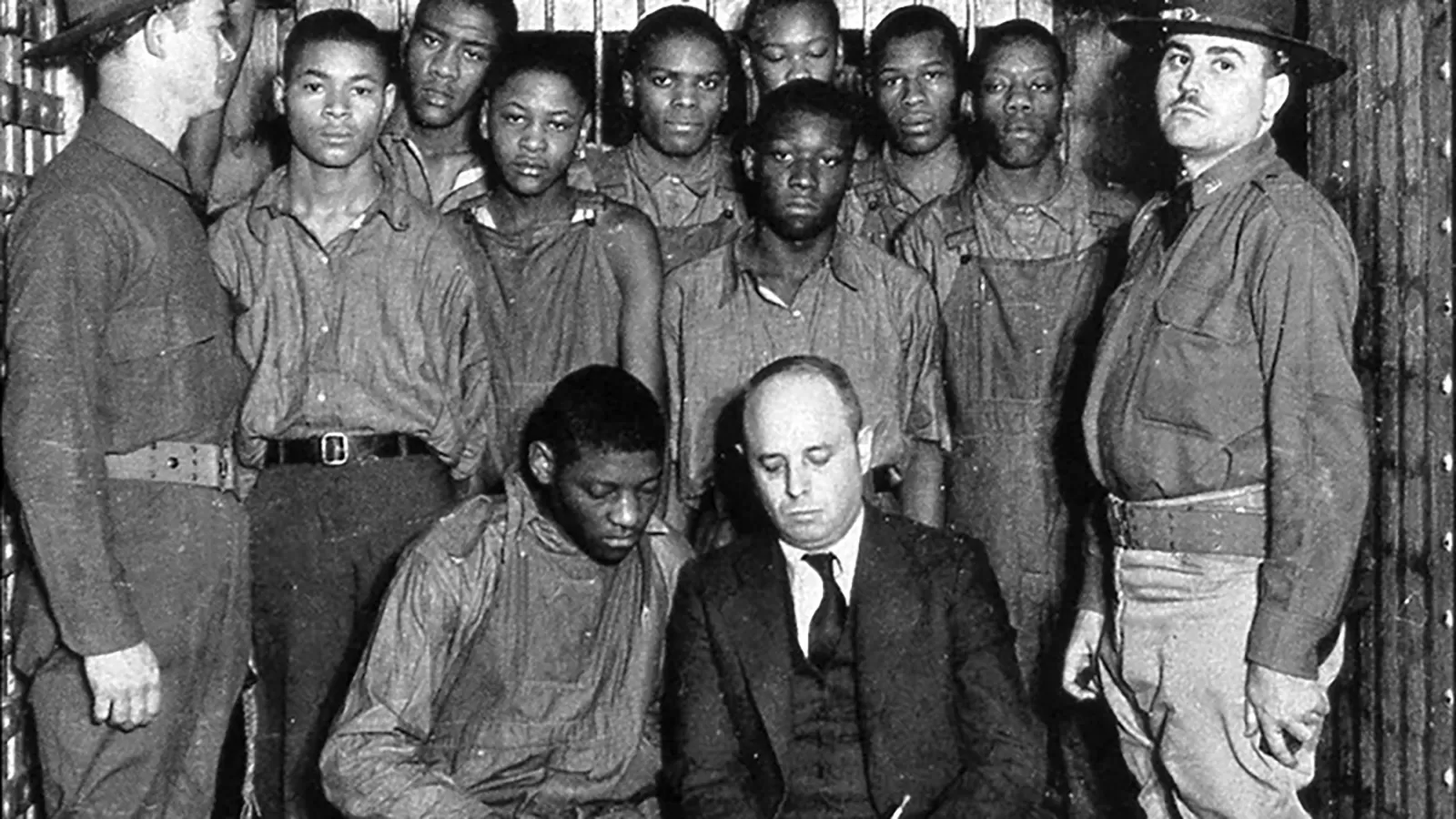

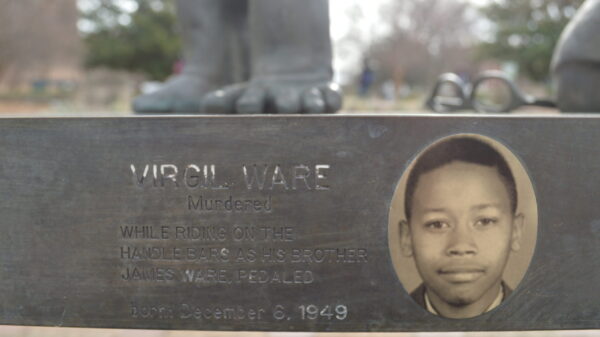

In 1931, a train ride in search of work during the height of the Depression nearly ended the lives of nine Black teenage boys — Clarence Norris, Jr., Charlie Weems, Ozie Powell, Andrew Wright, Leroy Wright, Olen Montgomery, Willie Roberson, Haywood Patterson and Eugene Williams — who were falsely accused of rape by two white women.

The young men endured courtroom trials, convictions, retrials and incarceration, collectively spending 130 years in Alabama’s jails and prisons for a crime they did not commit. Referred to by their supporters as the “Scottsboro Boys” because of where the first trial took place, for years they lived on Alabama’s death row where they could hear the buzz of the electric current as it coursed through the bodies of people being executed.

“From the get-go, they never had a chance,” said Larry Dane Brimner, author of ACCUSED!: The Trials of the Scottsboro Boys: Lies, Prejudice, and the Fourteenth Amendment.

By 1950, when the nine were all finally free, they faced a harsh future, some tolerating more prison time and others suffering from ill health, violence, suicide and early deaths.

Their legacy endures in several U.S. Supreme Court decisions such as the Powell v. Alabama ruling that all Americans have the right to receive effective legal counsel when accused of a serious crime.

“This was one of the first times that the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a State criminal court conviction,” said Dr. James R. Acker, a professor emeritus at the University of Albany’s School of Criminal Justice and author of Scottsboro and Its Legacy: The Cases that Challenged American Legal and Social Justice.

“Powell v. Alabama laid the groundwork for later Supreme Court decisions that provide effective legal counsel,” he said.

However, the plight of the Scottsboro Boys is not just an example of a gross miscarriage of justice from 90 years ago; it’s one that still has relevance today, according to criminal justice experts.

“One of the trials of the century that focused the attention not only of the nation but of the world on the administration of justice in the United States,” Acker said.

Many of the hallmarks of their case still exist in the justice system today, such as a lack of access to competent legal counsel, prosecutorial overreach, prosecution of children in adult court, disparate treatment of youth of color, lack of representative juries and capital punishment.

To fully understand the case and preserve an accurate accounting, Alabamans have worked to document the nine’s experiences, by keeping and maintaining records, artifacts, correspondence and photographs in county archives, and by telling their stories through current and planned museums, monuments and markers in Scottsboro, Decatur and Athens, where their trials happened and judicial decisions were handed down.

“We need to step back and stop seeing it as something historical, a thing of the past,” said Dan Carter, professor emeritus at the University of South Carolina’s History Department and author of Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South.

“It is very much with us today,” he said.

Train ride off track

Two white women, Victoria Price, age 21, and Ruby Bates, age 17, accused nine Black teenage boys of rape while they were all riding on a train through Scottsboro, Alabama, on March 25, 1931.

The teens ranged in age from 13 to 19. None were Alabamans; they were from Georgia and Tennessee. They were heading to towns to seek work with decent wages. Most did not know each other before that day. Two, Andrew and Leroy Wright, were brothers.

Scottsboro sheriff’s deputies arrested the youths and charged them with assault and then rape. Less than two weeks after their arrests, Judge Alfred E. Hawkins convened their trials in Scottsboro, lasting a total of 4 days.

“There was a general sentiment in a white-dominated society that by mixing Black men and white women, there was a presumption of impropriety,” said Acker.

Thirty minutes before the start of the first trial, Hawkins assigned two lawyers to represent all nine defendants who had not previously met them or investigated their case in preparation for trial.

Even though local attorney Milo C. Moody had not taken a case in years and Stephen R. Roddy, a Chattanooga real estate attorney, did not know criminal procedure and wasn’t licensed to practice law in Alabama, Hawkins proceeded with the trial.

Without medical evidence, the all-white, all-male jury convicted eight of the nine defendants of rape and sentenced them to death based on the contradictory testimony of the prosecution’s witnesses and the coerced confessions of some of the defendants against each other. In the case of 13-year-old Leroy Wright, the youngest Scottsboro defendant, the judge declared a mistrial because he felt Wright was too young to be sentenced to death.

“From day one, they were presumed guilty,” Carter said.

Reaction to the verdicts

The verdicts set off protests around the world, organized by the Communist Party of the USA and its legal arm, International Labor Defense. At that time, the communists actively organized on worker’s rights, especially in the South on behalf of Black workers, said Acker.

In addition to galvanizing public support for their defense through protests, rallies and letter-writing campaigns, the ILD fought with the NAACP over legally representing the nine, ultimately winning because they’d sought and secured the support of the defendants’ mothers. With the ILD’s backing, the mothers toured the country and abroad, speaking at rallies encouraging action to overturn the verdicts.

Liebowitz appealed their cases to the Alabama Supreme Court where the court upheld their convictions, and then to the U.S. Supreme Court where the court overturned their convictions.

“[The Communist Party of the USA] saved their lives,” Carter said.

Decatur’s Black leaders testify

During the second round of trials which were moved 50 miles away from Scottsboro to the Morgan County Courthouse in Decatur, Judge James E. Horton presided. Horton convened the trial for Haywood Patterson on March 27, 1933.

To show that the county was conducting an unfair trial by denying Blacks a place on the jury, Liebowitz called up Black leaders from Decatur to testify to the capability of Blacks to serve on the jury.

“It took a lot of courage to take a stand in a very contentious public trial,” said John Allison, archivist for Morgan County where most of the legal historical records on the Scottsboro Boys are preserved as well as the witness chair and witness stand from which Black leaders would have given their testimony.

Decatur native Frances Tate, founder of Celebrating Early Old Town with Art said the Old Town Community of Decatur helped to avert potential attacks by the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists on the defendants’ witnesses as well as the defendants’ lawyers.

“All during the trial, the Old Town Community was terrorized day and night by the klan shooting up the neighborhood. A 16-year-old Black boy, James Royal, was killed during one of those attacks,” said Tate.

According to press accounts, the home of one Black defense witness, E.L. Lewis, was burned to the ground, and he later died from poisoning. Another Black defense witness, Frank Sykes, moved to Baltimore because of threats and intimidation. The Ku Klux Klan was responsible for this, according to Allison.

Old Town Community members also protected Black reporters covering the case so that they could get their stories published.

“The Black reporters had to be bustled from house to house with guards who stood guard all night to keep them from being killed,” Tate said.

During the trial, the governor brought in the national guard to provide additional protection, surrounding the courthouse and the jail. Liebowitz also had armed guards accompany him throughout the trials.

“The threat was real,” Allison said.

Judge Horton sets aside the guilty verdict

On the trial’s last day, in a Hollywood-esque twist, Liebowitz pretended to give his closing statement and then called Ruby Bates as a witness for the defense.

In her testimony, Bates said the nine did not rape her; Victoria Price had directed her to make the false accusation. Bates and Price did not want to be prosecuted for violating the Mann Act, a law often used as an excuse to arrest Blacks, that made it a crime to cross state lines to engage in prostitution or other immoral purposes. Rather than face charges, Price and Bates falsely accused the nine Black teens.

The prosecution’s attorney grilled Bates about where she’d obtained her new clothes.

“The Communists,” Bates replied to that question and similarly responded to several subsequent related questions.

Bates’ testimony did not likely have the effect on jurors that Liebowitz had intended.

Once the trial concluded, Horton excused the jury where they were out for 22 hours.

On April 9, 1933, the all-male, all-white jury returned a verdict of guilty as well as a large jigsaw puzzle that they’d worked on.

A week later on April 17, 1933, Horton announced that he was suspending Patterson’s verdict and setting aside the remaining cases. He said he would reconvene the court in two months to discuss sentencing.

Two months later, on June 22, 1933, Horton delivered an hour-long statement at the Limestone County Courthouse in Athens before announcing his decision.

“The testimony of [the prosecution], in this case, is not only uncorroborated, but it also bears on its face indications of improbability and is contracted by other evidence, and in addition thereto the evidence greatly preponderates in favor of the defendant,” Horton said.

In a surprise move, Horton set aside the guilty verdict and ordered new trials.

“It was incredible that he did that, especially in the climate just coming out of the Depression and in the South at that time,” said Horton’s granddaughter Kathy Horton Garrett, who first learned about her grandfather’s actions when she was a teen in high school.

That decision impacted Horton’s future political prospects as Horton lost his seat in the 1934 elections and that eclipsed his hopes to serve on the Alabama Supreme Court, said Carter.

“Let justice be done, and may the heavens fall” was what Judge Horton learned on his mother’s knee, according to Garrett.

Ongoing appeals for justice

In Decatur starting in November 1933, Alabama’s Attorney General Thomas E. Knight, Jr. tried the cases for the third time. This time, the cases were before Judge William Callahan, a known white supremacist, in an action thought to be engineered by Knight.

All-white, all-male juries convicted all nine again and sentenced them to death.

Defense attorneys for the nine appealed the cases to the Alabama Supreme Court, which included Knight’s father, Thomas E. Knight Sr., where the court upheld the convictions in June 1934.

“It seems clear to me that Justice Knight Sr. clearly should have recused himself from sitting in a case where his son not only secured the convictions being challenged but also appeared before the Alabama Supreme Court to argue the case,” Acker said.

After the Alabama Supreme Court’s ruling, defense attorneys appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which overturned the convictions and ordered new trials, ruling in Norris v. Alabama and Patterson v. Alabama, that Alabama could not deny Blacks the right to serve on juries.

“This decision means that we must put the names of Negroes in jury boxes in every county in the State,” said Gov. Bibb Graves in a letter to judges and attorneys in 1935.

In the fourth round of trials, in January 1936, jurors again convicted the Scottsboro defendants. Rather than a sentence of death by execution, the jurors gave Haywood Patterson 75 years.

A year and a half later, jurors convicted Clarence Norris Jr. and sentenced him to death. Jurors convicted Andy Wright and sentenced him to 99 years. Jurors convicted Charlie Weems and sentenced him to 75 years.

However, in a surprise announcement in July 1937, the Alabama Attorney General dropped the charges against the remaining five — Olen Montgomery, Ozie Powell, Willie Roberson, Eugene Williams, and Roy Wright. All were released, with the exception of Ozie Powell, who pleaded guilty to assaulting a sheriff’s deputy and was sentenced to 20 years.

“I never understood it, and nobody ever explained it to me. But it was clear Leibowitz had made a deal with Alabama to free four of us, leave me behind with the death sentence and the rest with long prison terms. … It was the saddest day of my life,” wrote Norris in his autobiography.

According to documents released in late 1939, Graves made a deal with the Scottsboro Defense Committee to release the remaining five when the courts were done with the case — so long as the attorneys ceased their appeals.

Graves, however, didn’t follow through with the agreement.

“The state made a promise and then didn’t live up to it,” said Larry Dane Brimner, author of ACCUSED!: The Trials of the Scottsboro Boys: Lies, Prejudice, and the Fourteenth Amendment.

“This was a case of a politician putting his career over the lives of individuals,” he said.

Alabama authorities eventually released four of the remaining defendants from prison by 1950. One of the nine, Haywood Patterson, escaped from prison in 1950 to Michigan to live with his sister.

While they were ultimately spared Alabama’s electric chair, the young men’s lives were still irreparably changed.

“I have had a great struggle. But I want the world to know I am unbeaten,” said Patterson in his autobiography.

Norris returns to Alabama

More than a quarter-century later, Clarence Norris Jr. returned to Alabama.

This time he would not be imprisoned but would receive a pardon from segregationist Gov. George Wallace.

“I wish the other eight boys were around,” said Norris, the last living defendant in the Scottsboro Boys case, at a press conference after receiving the pardon on Oct. 25, 1976.

Three years later, Norris wrote The Last of the Scottsboro Boys in which he recalled his experiences since his arrest and his repeated attempts at obtaining a pardon.

“I was never guilty of anything except stealing a ride on a freight train during the Depression, just as poor whites were doing,” Norris, who died in 1989, wrote in his book.

Shelia Washington seeks justice for The Nine

In 1977, 17-year-old Scottsboro native Shelia Washington learned about the Scottsboro Boys case after finding an autobiography, Scottsboro Boy penned by Haywood Patterson under a mattress in her home.

After her stepfather took the book away, stating it was too awful for children to learn about, Washington eventually read it anyway.

Patterson’s book sparked Washington’s passion to commemorate the nine youths and preserve their legacy.

“One of the most dedicated people I’ve ever seen,” Allison said.

It took Washington years to raise the funds and gather items to display for her vision of a Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center to become a reality. The museum opened in 2010.

Washington also began a campaign to pardon the remaining three whose convictions stood, working with Professor Ellen Spears and other University of Alabama professors and students in 2013 to change Alabama’s law that did not allow posthumous pardons to be granted.

On Nov. 21, 2013, 82 years after the Scottsboro Boys were arrested, Alabama’s Board of Pardon and Parole granted posthumous pardons to the three who had not been pardoned or whose convictions had not been overturned during their lifetime: Haywood Patterson, Charlie Weems and Andy Wright.

“It would not have happened without [Washington’s] persistence,” Allison said.

Washington died unexpectedly at the age of 61 on Jan. 29, 2021.

“I miss her dearly,” said Lacey Smith, who currently serves as the interim director of the museum.

Plans are underway to renovate the museum providing the complete story of the Scottsboro Boys, Smith said.

Lard bucket letters reveal new evidence of pressure on Judge Horton

In 2016, Rebekah Davis, archivist for Limestone County, said that she was able to view hundreds of letters and telegrams that were sent to Judge Horton during the trial that Judge Horton’s daughter-in-law, Katherine Horton shared with her.

Horton’s late husband, Don Horton, had saved the letters and telegrams, organizing and indexing them, according to Horton’s daughter, Kathy Horton Garrett.

Davis analyzed the documents and said they shed new light on the pressure that Judge Horton faced in 1933 during the trial proceedings in Decatur.

“The eyes of the world were on him,” Davis said.

Of the hundreds of letters, Horton received about a dozen threatening his life.

“Some of the most vehement letters written to Judge Horton that were threatening were signed anonymously,” said Davis.

“He never regretted it,” said Garrett about her grandfather’s decision to set aside the verdict and order new trials.

Legacy

The Scottsboro Boys case impacts today’s justice system 90 years later in many important ways, such as the Powell v. Alabama ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court.

In his 2020 book, Alabama Justice: The Cases and Faces that Changed a Nation, Auburn University constitutional law professor Steven Brown cites Powell v. Alabama as a landmark case because it resulted in securing the right for all Americans to obtain effective legal counsel if they are accused of serious offenses.

“It was the first time that the court restricted states in some of their criminal justice procedures,” Brown said.

However, the lack of effective legal counsel is still an issue in many courtrooms, according to criminal justice experts.

“Like so many Supreme Court rulings there’s an unfortunate gap between the doctrine and how it works out in actual practice, so you and I can mouth the words ‘ineffective assistance of counsel is a constitutional violation,’ but when you look around in many courts today, that standard is given a little more than lip service,” Acker said.

“Much more needs to be done,” he said.

In addition to lack of effective counsel, other features of the Scottsboro Boys case continue to exist in the present-day justice system.

“False accusations of rape by white women against Black boys and men isn’t just a tragedy in the past, it negatively impacts how children are treated in the justice system today,” said Marcy Mistrett, the director of Youth Justice at The Sentencing Project.

Mistrett cited a case involving five Black and brown teenagers — Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Raymond Santana, Korey Wise, and Yusef Salaam — falsely accused of rape by a white woman in 1989 in New York City, recently highlighted by filmmaker Eva Duverney in the award-winning series “When They See Us.”

The teens, collectively known as the Central Park 5, spent between six and 13 years behind bars each before being released. The courts vacated their convictions in 2002, and the city provided a $41 million settlement in 2003 after 10 years of litigation.

“We’ve spent the past two decades trying to repeal harmful state policies passed in the name of the Central Park 5 case that sent tens of thousands of children — mostly Black and brown — into adult courts, adult jails and adult prisons every year,” said Mistrett.

Another example is the 1978 case in Decatur where Tommy Lee Hines, a 25-year-old Black man with a mental capacity of a 6-year-old, was accused of raping three white women, the subject of a recent book by Decatur native and historian Peggy Allen Towns Scapegoat: The Tommy Lee Hines Story.

An all-white jury convicted Hines of the crimes in 1979 and sentenced him to 30 years. Hine’s attorney appealed to the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals, which overturned the conviction and ordered a new trial. The court ultimately found Hines incompetent to stand trial and the state sent Hines to live in a residential home in Tuscaloosa, where he died in 2020.

“While the justice system has made improvements, there is a long way to go to ensure equitable treatment,” said Brimner.

Decatur’s Old Town Community’s role in the case

In Decatur, where the bulk of the Scottsboro Boys’ trials took place over a four-year period between 1933 and 1937, Decatur native Frances Tate is working to establish the Scottsboro Boys – Celebrating Early Old Town with Art Civil Rights Museum.

“We need to keep this history alive,” said Tate.

Tate grew up in the Old Town Community, the first neighborhood established in Decatur, and recalls the people who lived there and the businesses that were run by Black people and that their role in defending the Scottsboro Boys has been overlooked and unrecognized.

The museum will showcase the role of Decatur in the Scottsboro Boys’ trials and the struggles and victories in civil rights at the time, according to the museum’s website.

Tate has acquired property to establish the museum, including the house where Ruby Bates was housed during the trial. The city was set to demolish the house when Tates advocated to save it with the support of Decatur’s longest-serving city councilman, Billy Jackson.

Jackson, who has known Tate his whole life and grew up a few blocks from her, said that he strongly supports Tate’s vision of highlighting the Scottsboro Boys’ cases and sees the potential of the project.

“The impact is going to be enormous. There are some young people in the community who don’t know the history of the Scottsboro Boys case,” Jackson said.

Tate wants to ensure that the Old Town Community is recognized for its key role during the Scottsboro Boys trials. The museum will also feature the Tommy Lee Hines case.

The museum will show where Decatur was at a critical time in the community’s history and Decatur will have the opportunity to reflect on how far it’s come, Jackson said.

“We have an obligation as a community and as a city to support this project,” Jackson said.

Racial tensions recently erupted in Decatur in March 2021 over Councilman Billy Jackson’s call for the resignation of City Councilman Hunter Pepper about a Facebook post in 2018 when he was 16 years old about wanting to drive a car into a Black Lives Matters protest at the Galleria Mall. Pepper issued a statement where he apologized and said he made a mistake when he was young.

On June 13, 2021, Decatur Mayor Tab Bowling displayed a photo on his Facebook page of himself when he was a teenager shaking hands with Wallace in 1979. The photo remains on his Facebook page.

“We still have issues and hurdles that we need to cross as a community in Decatur,” Jackson said.

“This project will help us to get over some of those hurdles,” he said.

Tate’s vision is that the museum will be an experience for visitors and an opportunity to learn more about the legal aspect of the case and what the Scottsboro Boys and their families went through.

“When you leave this museum, I want you to be so motivated, so inspired that you want to go out in the world and make it better and not only want to make it better, but go out and do it,” said Tate.