Judging exclusively by the shape of its constitution, Alabama is a failed state, some sideways experiment in democracy gone horribly, horribly wrong.

The document, ratified in 1901 in a process we now know to be fraudulent, is approaching 400,000 words and will soon break the 1,000-amendment barrier. While its length is embarrassing, the destructive thing about what passes for our state’s fundamental governing law is how it concentrates power in the hands of Montgomery legislators and makes local self-determinism — especially when it comes to taxes — all but impossible.

The constitution also bears all the poisonous sins of Alabama’s bigotry, with multiple provisions on poll taxes and segregation, and its flaws shine most clearly in the myriad amendments, from the 2,700-word Amendment 489 (creating the Alabama Music Hall of Fame) to Amendments 597 (the one-sentence “Sportsperson’s Bill of Rights” that simply states “All persons shall have the right to hunt and fish in this state in accordance with law and regulations”), 884 (the Sharia law moral panic inspired “American and Alabama Laws for Alabama Courts”) and others that stand as a clear reminder of gutless political pandering.

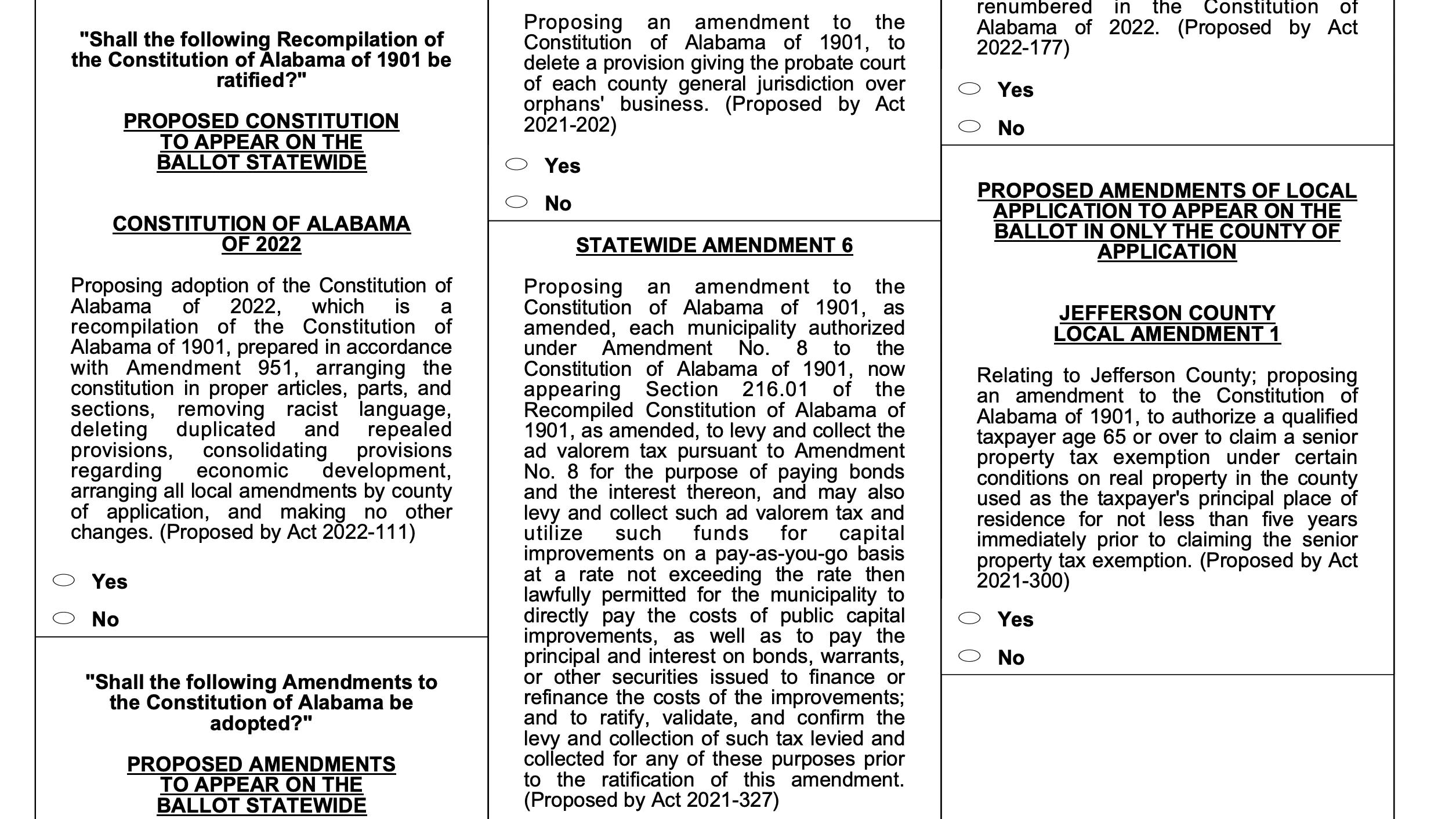

The Alabama Constitution of 2022, a measure now on the ballot, will fix none of those problems.

As set out in Amendment 951, this new(ish) document seeks only to remove racist language, delete duplicative and repealed provisions, consolidate measures regarding economic development and arrange local amendments by county — it’s those four things and “no other changes,” as 951 explicitly reads. This “new” constitution won’t end the ridiculous practice of deciding county issues like road maintenance, animal control or golf carts alongside what should be our most important guiding principles nor will it give us the tax reform our educational system so deeply needs.

But that doesn’t mean it’s not worth passing. Removing racist language — for example, Sec. 102’s ban on interracial marriage that proclaims, “The legislature shall never pass any law to authorize or legalize any marriage between any white person and a negro, or descendant of a negro” — is a step toward something better. Because while the language is inoperable thanks to both the Supreme Court’s decision in Loving v. Virginia and Amendment 667 (which, by the way, passed a statewide vote by only a 59-42 margin), it still persists in the document as a shameful sigil of intolerance. The recompiled constitution, however, removes both the original ban and the amendment that formally repealed it, and while there’s perhaps an academic discussion to be had about “not forgetting history” or some other claptrap, it seems like the altogether better proposition is the one that respects the rights and dignity of all Alabamians.

As my friend and Alabama Arise communications director Chris Sanders told me, the Constitution of 2022 doesn’t do what it could do or should do, but it does enough that it’s worth doing. The best argument for passing it, though, might simply be that it’s some small step toward getting rid of the 1901 document entirely. As a state, we’ve labored under it long enough as an enduring tribute to what committed racists of the early 20th century could accomplish. Whatever progress Alabama has made as a state has been in spite of it, not because of it, as then-Gov. Emmett O’Neal argued, “[Mlany of the provisions of our present antiquated fundamental law constitute insuperable barriers to most of the important reforms necessary to meet modern conditions” — and he was speaking in 1915. Former Gov. Albert Brewer wrote in 2001 that the constitution was a framework for “legislative detail rather than a fundamental charter of government” and that it “burdens our state’s ability to compete effectively for new business and industry[.]”

Yet those economic development and good government arguments pale next to the idea that the 1901 constitution was formulated specifically to deprive Blacks and the poor of their rights to participate in the state’s civic life. As I said to Huntsville’s WAFF, it is a fundamentally racist document, passed in a fundamentally racist era that fundamentally disenfranchises a great portion of the state of Alabama.

Men and women of conscience like Brewer have tried to fix it, replace it, do anything to give the people of this state the fundamental guiding legal principles they deserve, and they’ve have had at least some success. Popular support for progress crested with the Alabama Citizens for Constitutional reform and its founder Bailey Thompson’s work in the early 2000s, but amendments like 328, 904 and 905 have replaced entire articles, with some — especially 328’s restructuring of Alabama’s judiciary — making serious and important changes to state government.

In 1983, Alabama’s legislature — leery of a perhaps unpredictable constitutional convention — introduced a rewritten document and put it to the people as an amendment, one that would have scrapped and replaced the 1901 constitution in its entirety. But before the electorate could have its say, the Alabama Supreme Court declared the move to be an unconstitutional circumvention of the established convention process. The only way to adopt a new constitution “short of revolution,” the court concluded, was to call for a convention.

With its limited agenda and prior voter approval, the legislature has likely cured the procedural defects the state supreme court found 30 years ago, and if it passes, the Constitution of 2022 should stand up to any legal scrutiny. Yet even with the moral necessity of removing racist language, it remains incremental change.

Real, fundamental progress does require a revolution. Not of guns or bombs or chaotic Jan. 6-style terrorism but of political will and decency and an abiding respect for all Alabamians.

Until we have those things, we will forever be haunted by the specters of 1901.