As much joy as there is in relishing Alabama’s 49-27 win over Auburn in this year’s Iron Bowl and as much cringeworthy horror there is in the university’s decision to turn over the football program to a sketchy, abusive twit who possibly can’t be trusted with his own Twitter account, it’s important to note that Auburn isn’t just losing on the gridiron or in the game of public relations.

Because it also recently took a loss in the courtroom — one owing to both the First Amendment and, coincidentally enough, criticism of the athletic department’s outsized influence on the Plains.

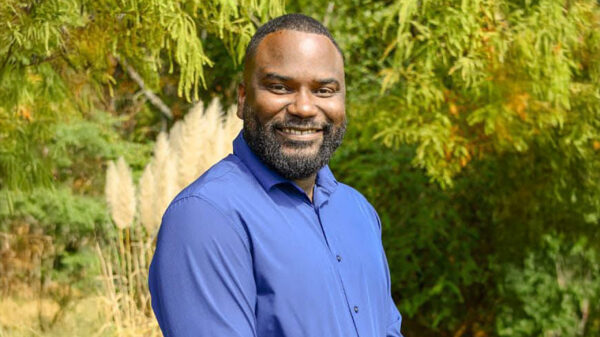

Michael Stern, an economics professor and former chair of his department, was awarded more than $600,000 in a suit against Auburn officials under a theory that he was unconstitutionally retaliated against when he spoke out regarding the university’s practice of stashing athletes in its public administration major, a scheme that at one point resulted in half of all such majors playing sports for Auburn. Stern argued — and a jury accepted — that once he began public criticism of athletics and the public administration major in 2015, certain actions taken against him by university officials, such as denying him raises and removing him as chair of the economics department, were done to punish him for that constitutionally protected speech.

If the First Amendment means anything, it’s that the government can’t punish individuals for speech that falls short of the legally proscribed boundaries of criminal acts like true threats and incitement. That same shield extends to situations in which the government is an employer, but that protection is tempered with the expectation that the state has the right to control the freedoms of its employees to effectuate the shared goals of the workplace. As an employee of Alabama A&M, I couldn’t logically expect to keep my job if I decided to devote long stretches of class time in my broadcast law course to debating which Ninja Turtle is best (Donatello) or whether Cincinnati chili is actually food (it is not) — that speech would be protected in other circumstances but wasting instructional time on it makes me a bad employee, and the government should have a right to dismiss or otherwise sanction ineffective members of its workforce. At the same time, though, I should have some freedoms to speak about issues that I think are important (those perhaps more critical than Midwest “cuisine” or how much I adore Donnie) while not facing reprisals from the university.

The Supreme Court first attempted to strike this balance between government as employer authority and employee as public citizen speaker freedoms with 1968’s Pickering v. Board of Education. In that case, an Illinois high school teacher was fired after he wrote and published a letter to the editor that was critical of school board spending and attempts to coax voters into passing a bond referendum. Using money for athletics was fine, Marvin Pickering wrote, provided that other school needs were met. “To sod football fields on borrowed money and then not be able to pay teachers’ salaries,” Pickering observed, “is getting the cart before the horse.”

In overturning Pickering’s dismissal, the court found that where “the fact of employment is only tangentially and insubstantially involved in the subject matter of the public communication made by a teacher,” then Pickering was due the same rights as anyone else writing into the paper on an issue up for public debate. In subsequent cases, the Supreme Court refined the public employee speech into a four-part test that, again, tries to balance an individual employee’s right to free speech with the government’s need for an operative workplace: 1) whether the employee spoke as a citizen on a matter of public concern, 2) whether the employee’s interest in speaking outweighs the government’s interest in efficient public service, 3) whether the speech played a substantial role in the adverse employment decision and 4) whether the government would have made the same decision absent the protected speech in question.

After applying that test to Stern’s suit against Auburn, it’s not hard to see why his claims both survived a motion to dismiss and ultimately resulted in half a million dollars in his bank account. Under the first part of the test — whether the speech was undertaken as a private citizen on a matter of public concern — the Supreme Court has outlined a series of factors such as the employee’s job description and where the speech took place as helping to determine if the speech in question was speech made as an employee or speech made as a private citizen.

In Stern’s case, he spoke as the chair of the economics department, not someone who had anything to do with either the public administration major or athletics. He also spoke on multiple occasions on many different platforms including The Chronicle of Higher Education, where he was quoted as saying, “There must be penalties for those who don’t play ball, and there have to be rewards for those who do. Auburn has been cleansed of dissent” — a timeless statement about the affairs of the Plains if there ever was one. Those facts suggest he was a public citizen who just happened to be employed by Auburn, rather than, say, the leadership of the public administration program speaking out to protect their fiefdom.

In their motion to dismiss, the Auburn defendants chose not to quibble over the second part of the Pickering test (there was likely no proof that Stern’s speech caused any harm to the orderly operations of the university), choosing instead to focus on parts three and four. Specifically, they argued Stern’s dismissal as chair was unrelated to his criticism of the public administration major; the professor, however, was able to cite conversations in which he was directed to keep complaints “in house” and an email where he was told his remarks caused “collateral damage” in a “very public way,” suggesting Auburn administrators were both aware of and irked by his crusade and thereby making it a question for a jury to determine whether the speech motivated the adverse employment actions against Stern.

Finally, as to the fourth prong of the Pickering test, Auburn administrators offered a handful of non-speech related factors as to why Stern was removed from his post as chair of the economics department, such as his refusal to follow a normal chain of command, absence from leadership meetings and his decision to not complete a required self-evaluation. But as the court determined in rejecting their motion to dismiss Stern’s claims, while those were all credible factual points, they did not establish as a matter of law that the professor would have been stripped of his chair position regardless of his protected speech — meaning that, again, it would be up to a jury to decide the question.

While Stern did win after presenting his case to a jury, the umbrella of protection for government employees under Pickering is not particularly extensive and it comes with some glaring, almost nonsensical holes, as two cases against my employer (Alabama A&M) demonstrate. In 2017, the Alabama Supreme Court dismissed a suit by a former journalism professor who criticized several funding and staffing issues at AAMU only to be later fired. Even if the professor could show she was speaking out about a matter of public concern, the court concluded that under the fourth prong of the Pickering test, AAMU clearly had a non-speech related justification for her dismissal in that she was one of seven faculty members selected to be let go because of a crushing budgetary shortfall.

A 2018 case showed the precarious position of whistleblowers under Pickering as a federal trial court dismissed a claim by a former AAMU secretary who was fired after alleging that other employees were abusing the university’s leave system and violating other policies. The court found that under the first prong of Pickering, the secretary was neither speaking out as a citizen nor was it a matter of public concern. “The First Amendment,” the court concluded, “simple does not empower public employees to constitutionalize their employee grievances” — and that applies even when those grievances are about public workplace wrongdoing. As Alabama law professor Ronald Krotoszynski concluded when writing about the need to strengthen constitutional protections for whistleblowers, “[T]he Supreme Court has failed to recognize and incorporate an important First Amendment value in the context of government employee speech: the clear relationship of government employee speech to holding government accountable through the democratic process.”

It is settled law that government employees cannot be made to give up their right to free speech as a condition of their employment. Yet the Professor Sterns of this world — the crusaders, the malcontents, the agitators fighting for something better for all of us — do not have all the protections they need.

That, though, is a fight for another day.

For now, it’s enough to savor one more Auburn University loss.