After six months of arguments, attorneys’ fees and near misses, Alabama A&M finally joined Alabama State University in signing a four-year agreement on Tuesday to continue the Magic City Classic in Birmingham.

All of that angst and upheaval resulted in: $400,000 less money.

Instead of a four-year deal that pays each school $4.8 million, the two schools will now take home just $4.6 million, according to the terms of the contract obtained by APR.

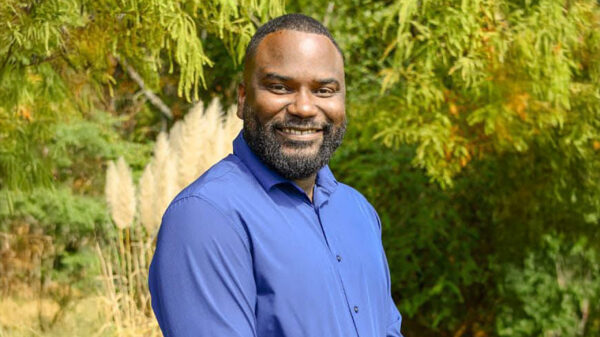

“These two deserving HBCUs will receive the highest guaranteed payout in the history of HBCU athletics,” said Perren King, Executive Director of the event, in a statement. “This guarantee is higher than some FBS bowl game payouts. We would like to applaud both presidents for being extremely thoughtful in achieving the best outcome for their constituency.”

The new deal is actually two separate but identical deals with the two universities, paying each “home” team more money. For example, under the new agreements, A&M will receive $1 million payout from ASC in 2024 and 2026, the years in which it is the designated home team, but only $300,000 in 2023 and 2025. Combined with the payouts from Birmingham and Jefferson County and the average annual take for each school is $1.15 million – down from $1.2 million annually in the original agreement offered in April.

Getting to this point has been one weird and wild ride for the parties involved, which include not only officials with the two universities but also state lawmakers, Birmingham city officials and the higher-ups at the Southwestern Athletic Conference. All of them trying to save an event with a multi-million dollar impact on the city of Birmingham and the two universities, and most of them at a loss for why the deals kept falling through.

The holdout was A&M, and school officials never hid that fact.

“We’re not going to be pushed around,” said Shannon Reeves, A&M’s vice president for government affairs, just after the school walked away from a deal two weeks ago. “We believe our position is not unreasonable and we’re going to stand our ground.”

That’s, of course, an admirable stance to take. The problem, however, is that it has never been quite clear just what A&M’s position is.

The first salvo in this six-month war was fired in April, when, after months of negotiations that dated back to the days just after the 2022 MCC, A&M officials, without warning, bailed on a new four-year deal. It was such a surprise that ASU President Quinton Ross had signed the deal, believing after a conversation with A&M President Daniel Wims, that the negotiating was over and a satisfactory agreement was reached.

The next thing anyone knew, A&M’s legal counsel, had fired off a letter to the City of Birmingham and Alabama Sports Council, which will be the promoters of the game under the just-signed contract and have been promoting and managing the game for the past 23 years, stating that A&M was no longer comfortable with a four-year agreement. Instead, A&M’s attorney Rochelle Conley wrote that while the school was in “substantial agreement with the provisions of the contract,” it wanted a two-year deal.

That demand threw a serious kink into the negotiations, since ASC had based the payouts to each school on its ability to secure four-year agreements – alongside the four-year guarantee that Birmingham had offered the schools – with various sponsors and to make four-year deals with various vendors.

At that point, things turned ugly. ASU and ASC moved forward with an agreement for the 2023 game, since it was technically ASU’s home game. That agreement paid ASU significantly more money than A&M.

Conley sent more letters, threatening lawsuits and stating that the game was joint property of the two universities. At the same time, A&M posted a story on its athletics website which essentially accused ASC of potentially shady accounting practices because, the story claimed, ASC officials wouldn’t disclose the financial records from the previous MCC games.

In a lengthy and detailed response, ASC responded to various points raised by the story, and specifically to the allegations that there had been “a lack of transparency” in regards to the financials.

“The management agreement between ASC and the Universities required that ASC make all financial records available for inspection or audit by either University,” the ASC response read. “The only time records were requested was on November 2, 2022, following the completion of the 2022 MCC, at which time AAMU’s General Counsel requested bookkeeping records be provided for the MCC Events of 2017-2022 on or before November 10, 2022. ASC provided the requested information within hours, except for the 2022 MCC information, noting the 2022 records weren’t complete yet due to the event ending a few days prior, but would be sent with the 2022 settlement as done each year.”

In fact, ASU and A&M had jointly requested the financial records during the negotiations that were ongoing after the 2022 MCC. According to a source at ASU, university officials reviewed those documents and were satisfied that an increased payout to $1.2 million per year for each school would be fair.

A&M officials said that wasn’t good enough. Reeves told APR that the records provided were not the complete financials. ASC disputes that characterization.

Then, according to those involved in the negotiations, the A&M position began to slowly morph – moving from concerns about a four-year agreement to concerns about the financials to concerns about ASC officials not agreeing to a sit-down meeting in Huntsville to concerns about putting the game’s promotional contract up for a bid.

Through it all, ASU officials were apparently dismayed by A&M’s actions.

“No one could understand what they were trying to accomplish,” said a source involved with the negotiations. “It never made sense, because, let’s say you break down all the numbers – how much each chicken wing costs and what they got for parking, etc. – and you total it up, you’re talking about maybe a few thousand dollars. We went through all this for months and negotiated a deal that pays the schools – at that time – $4.8 million. And you’re going to blow things up over maybe a few thousand dollars? When you have zero risk and zero responsibility? And all you have to do is show up and get off the bus? It was crazy.”

But A&M’s shifting position on certain aspects wasn’t what drew the most anger from those helping to push a deal. In fact, most parties involved could understand A&M’s hesitancy in some regards, and its desire to get a complete accounting of the monies generated by the game. Likewise, they could understand seeking a bid to see if other entities might offer more money.

“This was a new administration taking over and they were hesitant because they wanted to do a good job and get the most money for a great product,” said a source who served as one of many unofficial mediators during the negotiations. “That’s an admirable position.”

But what left A&M officials drawing the most ire was their timing and them repeatedly walking away from deals they had agreed to.

On at least two occasions, A&M officials gave every indication, according to multiple sources, that they planned to sign an agreement, and then the parties involved received a letter from an attorney indicating that there was another problem.

Most recently, after a late-August meeting, the parties believed a deal was all but signed. Various members of the media received calls that a deal was imminent and that “the nightmare is over,” as one official involved put it.

The next day, a letter showed up at the ASC offices from a new A&M attorney and informed the promoters that they would not be allowed to use any images or logos from A&M. And another deal was dead. At the same time, the school told officials involved that a new promoter had been hired, only to then have that promoter issue a press release saying it had not been retained.

“It wasn’t negotiating in good faith,” said one official who was involved in the process. “They knew they weren’t going to sign and they let the process run on and waste time. And they didn’t say what they wanted. That’s what really got people.”

In the end, it was all for nothing. Or, well, it was all for $400,000 less.