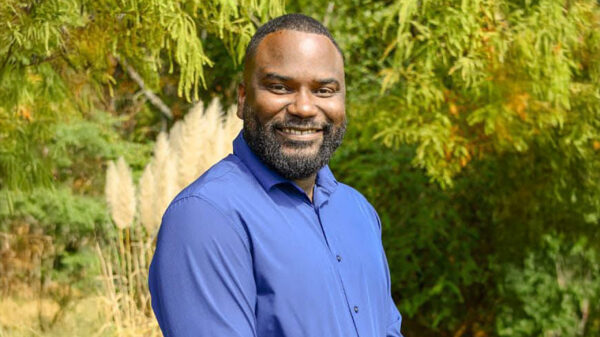

As a coalition of birthing centers and midwives squares off in court against the Alabama Department of Public Health, the state health agency has released its annual statistics on infant mortality, highlighting who Certified Professional Midwives (CPM) serve in the state.

The Fifteenth Judicial Circuit has blocked the ADPH from halting the operations of CPMs and birthing centers while litigation is underway.

The coalition of midwives argues that their services are increasingly necessary as the state faces high infant mortality rates, and more counties become deserts for maternal healthcare.

The crisis disproportionately affects Black mothers and infants, and poor women, but the statistics show midwives overwhelmingly serve white women and women who can afford to pay.

CPMs delivered just 330 babies last year — 0.6 percent of the 58,000 babies born in Alabama in 2022. Licenses have been available in the state since 2019, and as of July 2023, only 22 CPMs are licensed in Alabama.

Out of those 330 deliveries, at least 94.5 percent were self-pay. The statistics report eight of the deliveries as “other/unknown,” while the remaining 10 deliveries are categorized as “private.” The trend has been similar since 2020. In three years, Medicaid has paid for only one delivery.

These deliveries can cost between $4,000 and $12,000.

The statistics also show that 87.3 percent of the women served by CPMs in 2022 were white. Out of 330 deliveries, only 25 involved Black mothers; 11 Hispanic women had CPM deliveries, and seven other women of unidentified minority status. The remaining 228 deliveries were white babies.

The concept of non-nurse midwives has been controversial in Alabama for decades.

In 1976, Alabama outlawed the practice of all non-nurse midwifery, except for a narrow subset of traditional midwives with valid permits under the old rules “until such time as [the midwife’s] permit may be revoked.” Within five years, the legal practice of non-nurse midwifery effectively ended in Alabama, as officials revoked or refused to renew or grant more permits. These regulatory changes disproportionately affected Black midwives in the state, rendering most of their practices illegal. For nearly 50 years, traditional midwifery remained illegal in Alabama, enforced by state prosecution of traditional midwives who attempted to continue practicing.

In 2017, after prolonged advocacy from the midwifery community, the Alabama Legislature passed a law allowing non-nurse midwives to practice in the state, creating licensure for certified professional midwives and a State Board of Midwifery to oversee their practice. In January 2019, Alabama granted the first state licenses to Alabama CPMs.

The coalition of midwives and birthing centers suing the ADPH argues that the practice is essential as Alabama faces a maternity health crisis. However, a map showing counties where CPMs were present at deliveries reveals most in Alabama’s most populated counties, with few, if any, deliveries in the Black Belt, where access to quality maternity care is a major issue.

The coalition also argues against burdensome ADPH regulation, noting no major issues with deliveries at birthing centers, but also acknowledging that such centers only accept low-risk pregnancies.

The ongoing legal battle will bring closer scrutiny of the statistics and data in the latest ADPH report.

The litigants involved in the court case could not be reached for comment.