According to the so-called Department of Government Efficiency’s website, earlier this year the leases for both the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s office in Mobile and the Mine Safety and Health Administration’s office in Birmingham were marked to be terminated.

Larry Spencer, the vice president of United Mine Workers of America District 20, told APR that the MSHA “watch over [the mine operators] and keep them following the law and keep our people safe.” Members of UMWA locals in District 20 work at the Warrior Met Coal Mine in Brookwood and the Oak Grove Coal Mine in Jefferson County.

Established by the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977, the MSHA issued over 94 thousand citations and collected $68.5 million in fines in 2024 alone.

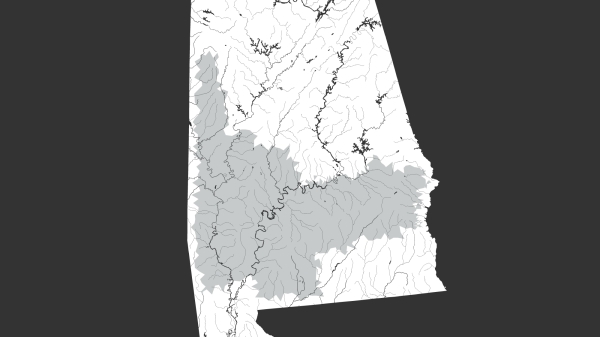

In addition to serving as a field office for MSHA inspectors working in Alabama, the MSHA’s Birmingham office is also the district office covering “Alabama, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, parts of Tennessee, Virgin Islands” and 32 counties in Mississippi.

The mineworkers’ union isn’t “hearing anything as far as them shutting this office down” yet, Spencer said, but “that doesn’t mean that that’s not going to happen under this administration.”

Major layoffs have already upended the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, a federal agency responsible for essential safety research including work on coal miners’ respiratory health.

Jordan Barab, who served as deputy assistant secretary of labor for OSHA from 2009 through 2017 and now runs the workplace safety newsletter Confined Space, described those layoffs to APR as “basically the destruction of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health” and said they would “inevitably lead to more injuries, illnesses and deaths of workers.”

Barab also said OSHA is already spread far too thin given its current funding, vividly illustrating that point by saying that “if OSHA were to inspect every workplace in the country just once, it would take them 185 years.”

“It’s a small agency already totally inadequate to fulfill its mandate, which is the safety and health of 158 million workers and 11.5 million workplaces,” he stated.

Given these pre-existing difficulties, closing Alabama’s MSHA and OSHA offices could have major consequences for the day-to-day safety of Alabama’s coal miners and other workers.

Spencer told APR it’d be “devastating,” pointing out that the coal mines in Alabama “are some of the deepest and dustiest and gassiest mines in the United States.”

However, despite over a month passing since the MSHA and OSHA’s leases were marked as terminated on the DOGE website, whether the two locations will actually be closed remains unclear.

In a press release earlier this week, UMWA president Cecil Roberts stated that as far as the union has been able to find out, “MSHA personnel still have no idea if or when they will be moving to a new location or even if they will have a job any longer.”

Two members of the House Committee on Education and Workforce—Bobby Scott, D-Virginia, and Ilhan Omar, D-Minnesota—have sent two letters to the Department of Labor asking what will happen to MSHA offices around the country. APR was told yesterday that despite almost a full month passing since the second letter was sent, neither letter has been answered.

With this level of minimal transparency, Barab says anyone worried about workplace safety needs to be watching out for the forthcoming “RIFs,” or reductions in force plans, for OSHA and the MSHA, as well as the 2026 budgets.

Cutting OSHA’s budget any further, even just by keeping it flat during a period of inflation and growing costs, will “certainly lead to more injuries, illnesses and deaths,” he asserted.

A U.S. General Services Administration spokesperson did tell APR though that the possible lease termination for the MSHA office is part of a larger strategy of “actively managing leases,” a tactic they claimed will “often allow us to enhance space utilization and secure better terms for the government.”

“In instances where the current space remains the most suitable option—whether temporarily or longer term—we are adjusting our approach,” the spokesperson said. “For these agencies, we are either rescinding termination notices or, in some cases, not issuing them at all.”

They also stated that “GSA’s letters of intent to terminate have no immediate effect and do not mean the lease has been terminated.”

But this description of the state of federal leases appears to contradict the “total savings” numbers available on the DOGE website.

Cancelling the lease of the Birmingham MSHA office is marked as carrying a total savings of $1,729,259. Ending the lease on the Mobile OSHA office is similarly associated with a total savings of $8,113.

In both cases, the total savings figures appear very close to the amount of rent that would be paid between the effective dates of the lease cancellations reported by the Associated Press and the expiration date of each lease according to a GSA spreadsheet.

If the offices were replaced, even with significantly cheaper locations, then DOGE’s total savings numbers would be drastically overestimated. The GSA spokesperson did not respond to a follow-up question from APR attempting to clarify this point.

Former assistant secretary of labor for OSHA Dr. David Michaels has also explained in an opinion piece for Industrial Safety & Hygiene News that he believes closing the nation’s workplace safety offices would end up costing both money and lives.

“To save a relatively small amount of money by ending some leases, Musk’s team will disrupt the functioning of already under-resourced offices, including the ones not being closed,” Michaels complained.

He wrote that consolidating OSHA’s offices would require inspectors to travel further, and therefore pay more, to inspect worksites across the country. And if, say, the Baton Rouge office is closed, “enormous oil and petrochemical facilities with significant safety and health hazards … will be inspected even less frequently than they are now,” which could have massive social costs if some dangerous lapse isn’t caught as a result.

Asked about how mine operators might behave without regular MSHA inspections, Spencer said that “some of them operate safer than others, but if you don’t have somebody looking over your shoulder, you know you tend to do things that aren’t always in the best interest of the people.”

According to the MSHA’s Mine Data Retrieval System, Warrior Met Coal has been issued over $1.3 million in penalties for various regulation violations at its two mines since April 2024, although most of these penalties are currently being contested. The specific regulations allegedly violated ranged from a requirement to promptly alert the MSHA about injuries that may lead to death to maintaining a proper ventilation plan, amongst many others.

“To me, [the MSHA is] a very important agency,” Spencer stressed. “I mean, they need to be there to watch over and make sure all of us do the correct thing, and we just don’t need to have any more disasters like we had in 2001 down at Jim Walters No. 5, when we had those 13 people killed in the explosion.”

“We definitely don’t want to see anything like that happen, or even a individual lose their life or a limb or anything,” Spencer continued. “We want them to come out and be able to be safe in the mines and be able to come out and go home and be with their family.”

A Department of Labor spokesperson told APR that “Mine Safety and Health Administration inspectors continue to conduct legally required inspections and remain focused on MSHA’s core mission to prevent death, illness, and injury from mining and promote safe and healthful workplaces for U.S. miners.”