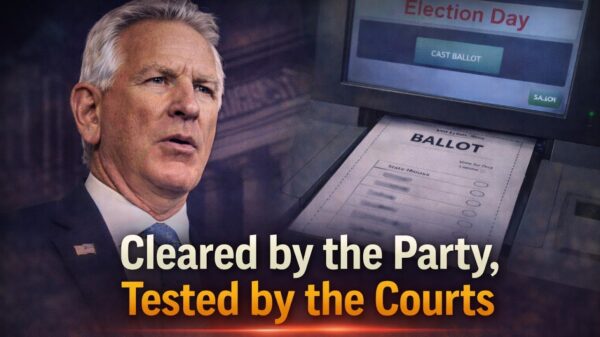

U.S. Sen. Tommy Tuberville has crossed the Rubicon.

He has declared his candidacy for governor of Alabama. And, at least for now, there is no serious opposition in sight. A sitting U.S. Senator entering a governor’s race is rare enough — rarer still is the prospect that he may face no credible challenger at all. If that holds, Tuberville would become only the third non-incumbent in Alabama history to be elected governor without facing an opponent.

The last two times that happened were nearly two centuries ago. In 1825, John Murphy was elected unopposed as the successor to outgoing Governor Israel Pickens. Four years later, Gabriel Moore, then serving in Congress, also ran without opposition. Both men received 100 percent of the vote. But those elections occurred in a very different Alabama — one still in its infancy, shaped by tightly held party control and minimal public contest.

Today, such political quiet is no longer the norm. Or at least, it shouldn’t be.

For several years, Lt. Gov. Will Ainsworth appeared to be the strongest candidate for the state’s highest office. He built a network, chaired key commissions and seemed poised to launch a campaign. But when Tuberville’s name entered the arena, Ainsworth stepped aside. So did other notable Republicans, many of whom had long harbored gubernatorial ambitions. Whether out of calculation or caution, they chose to stand down.

Tuberville enters the race with more than celebrity status. His tenure in the U.S. Senate has kept him in the national spotlight, often more for controversy than consensus. His hold on military promotions, his sparse legislative record and persistent questions about his residency have drawn criticism. Still, none of it appears to have dented his support among Republican voters — or within the party’s leadership.

In fact, few party officials seem inclined to raise those issues at all. Loyalty to the brand outweighs concern over the résumé. In today’s Republican Party, dissent is a risk, and silence is often rewarded.

Yet even in Alabama, history warns against presuming political inevitability. A dark horse could emerge — someone with the conviction to challenge not just Tuberville, but the creeping assumption that public office is simply granted, not earned. But for now, no such figure has stepped forward. Perhaps they are waiting. Or perhaps, like so many others, they’ve already decided the cost is too high.

There are forces within the state — donors, business leaders, civic advocates — who would welcome a real contest. They understand that democracy functions best when ideas are tested and leadership is earned, not inherited. But political courage is no longer in fashion, especially in a party more interested in unity of message than diversity of thought.

As John Stuart Mill warned, “The worth of a state in the long run is the worth of the individuals composing it.” If Alabama’s political class chooses to remain quiet, and its voters accept the absence of choice, then the verdict will not belong to the candidates — but to the people themselves.

Across Montgomery, you can feel it in the silence. Endorsements never requested. Debates never scheduled. A race that may be decided before it ever begins. For now, it’s not a campaign. It’s a slow, ceremonial drift toward coronation.

No Cassandra has stepped forward to lift the veil. No Oracle predicted that Tuberville would seek the governorship. Yet here we are, watching the future of Alabama narrow into a contest of one.

It is not Fate that decides unchallenged power — it is the failure of others to challenge it. Perhaps the race is not unopposed by destiny, but by the quiet retreat of those who once dreamed of leading.