“Here come the police! I ain’t going to jail!” yelled Lorenzo McCall, 16, as he looked at his friend Johnnie Robinson, 16, in the afternoon of September 15, 1963.

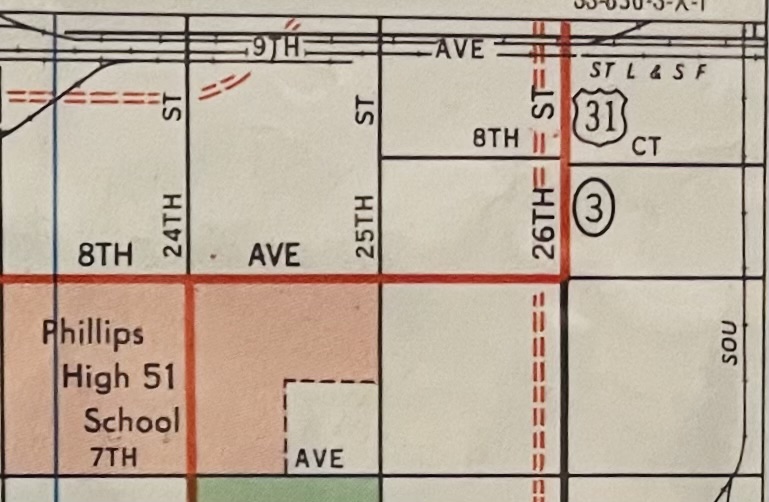

Birmingham police officers in car No. 45 chased Lorenzo McCall, his brother Doug McCall, 17, and Johnnie Robinson on 26th Street North and into 8th Alley in Birmingham.

Minutes later, Birmingham police officer Jack Parker, 48, holding his shotgun out of the left rear window of the police car, pulled the trigger. The shotgun pellets hit Johnnie Robinson in the back.

Doctors pronounced Johnnie Robinson dead at Hillman Hospital at 4:55 p.m.

While early national news reports stated that Johnnie Robinson ignored police orders to halt, multiple witnesses said that they did not hear Officer Parker give a verbal warning before he fired his shotgun.

Those witnesses would not be interviewed by Birmingham police detectives or called to testify before the county grand jury. Birmingham police’s investigation concluded after only two hours, and a county grand jury dismissed all charges.

The FBI uncovered many more witnesses who saw the shooting. Yet, a federal grand jury would also dismiss all charges a year later.

Officer Parker ultimately faced no consequences for shooting and killing Johnnie Robinson. Parker retired in 1973 after 25 years on the Birmingham police force.

The City of Birmingham never provided any kind of financial settlement or support to Johnnie Robinson’s family after his death.

The U.S. Department of Justice reopened his case only to close it after a cursory review, stating that there was no one to prosecute since Parker had died in 1977.

There was no justice for Johnnie Robinson, but more than 60 years later, his family fondly remembers him. Birmingham is finding ways to ensure his story is told.

Johnnie Brown Robinson

Johnnie Brown Robinson was one of five children of Martha Manning Robinson and Johnnie Robinson, Sr. He lived in the Central City section of Birmingham.

Johnnie Robinson enjoyed riding bicycles and loved playing sports – baseball, basketball and football, says his younger brother Leon Robinson in an interview at his home in Birmingham in May 2025.

“I used to try to follow him all the time, but he used to run me back because he was the big brother,” says Leon Robinson, while letting out a quiet laugh, in an interview at his home in Birmingham in May 2025. “He was trying to keep me out of trouble, trying to keep me out of things.”

As the Robinson family had few resources, Leon and Dianne Robinson went to live in 1956 at the home of their father’s sister, Daisy McConico, in the Norwood neighborhood about two miles north. While Johnnie Robinson stayed with his mother in the Central City area, the siblings regularly saw each other and their mother.

His family experienced tragedy in 1958 after Johnnie Robinson Sr. confronted a neighbor, Eugene Matthews, over the harassment of his sister, Clara Brown. The neighbor shot and killed Johnnie Robinson Sr. on his porch in front of Leon and Dianne Robinson, ages 8 and 10 at the time. Matthews served time in prison for the murder.

After some time passed, Martha Robinson started a new relationship with Lester Lee, who regularly beat her, according to Leon Robinson.

The family experienced further tragedy when Martha Robinson’s new boyfriend threw a can of baby food at her. The can missed her and instead hit their infant daughter, Debra Louise, who did not receive timely medical attention and died.

“They weren’t together no more after that,” recalls Leon Robinson.

In September 1960, Birmingham police arrested Johnnie Robinson for delinquent behavior. The Jefferson County Family Court sent him to the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children, located more than 100 miles south of Birmingham in Mt. Meigs, Alabama.

The segregated facility housed Black children ages 12-18, forcing them to work long hours in the surrounding fields owned by whites who served on the Mt. Meigs board. Staff subjected the children to extreme physical and sexual abuse and denied them food, clothing, and medical care. The facility did not provide educational or rehabilitative programs.

Conditions were so abysmal that in April 1963, the Alabama legislature created a special committee to investigate the Mt. Meigs facility and juvenile probation officer Denny Abbott initiated a successful federal class action lawsuit over the forced labor, horrific abuse and appalling conditions, chronicled in his book, They Had No Voice.

“Every first Sunday we had to go and visit him,” says Leon Robinson. “The facility was very rough, with fights all the time, and he had to work in the fields.”

Johnnie Robinson spent about 18 months at Mt. Meigs.

“He always talked to me and told me that he didn’t want me to get into the same situation that he was in,” recalls Leon Robinson.

In early September 1963, Johnnie Robinson came home from Mt. Meigs. He was set on attending Hayes High School in September 1963.

Map of 8th (Court) Alley and 26th Street North

Teen dispute

In the wake of the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church on September 15, 1963, Birmingham police officers patrolled the city to respond to violence that afternoon, according to press reports.

Charles Angelo, who managed the Central Esso Service Station on the corner of 8th Avenue and 26th Street North was working outside that afternoon. At 3:30 p.m., Angelo saw several Black teens standing on 26th Street North and next to them, a carload of white teens in a car, according to a statement he gave the FBI.

The Black teens standing on 26th Street North were Johnnie Robinson, who lived in the neighborhood and his friends Ernest Jones, 16, and William Gunn, 16, who both worked on 26th Street North. They were joined by Lorenzo McCall and his brother Doug McCall.

A group of white teens in a red and white 1954 Ford four-door automobile stopped their car at a red light on 26th Street North. Marvin “Bud” Kent, 18, who owned the car, was driving.

The car had a confederate flag draped over it and a sign, ”Negroes go back to Africa” as well as pro-segregation slogans written in shoe polish on all four sides of the car, “Glenn backs West End,” “Woodlawn backs West End” and “Boycott” in support of the white boycott of Birmingham schools organized by the National States Rights Party.

Kent was in the car with Ann Shirley, 18, Janice Montgomery, 16, Jimmy Sparks, 16, Sidney Howell, 18, and Don Sykes, 17.

Angelo saw an interaction between the two groups of teens, but he couldn’t make out what they were saying to each other.

“Four of the negroes started hollering at us,” said Kent in his statement to the Birmingham police.

“What’s wrong with you now? Can’t you get out and fight?” shouted the Black teens, according to Sidney Howell, who later gave a statement to the Birmingham police.

One of the white teens in the car threw a glass soda bottle at the Black teens standing at the corner, according to William Gunn in a statement to the FBI.

One of the Black teens responded by throwing a rock at the car, reportedly, but witnesses could not identify which youth.

Police response

Nearby on 8th Avenue, four police officers in Birmingham’s all-white police force in patrol car #45 were moving east between 25th and 26th Streets North. Officer Paul C. Cheek, 35, was driving with Officer J.E. Chadwick, 54, in the front passenger seat. Officer Jack Parker, 48, was in the back of the car on the driver’s side. Officer Bill Haynie, 56, was sitting in the back seat on the passenger side. Their car was three cars back from the traffic light on 26th Street North.

The police officers did not see the start of the altercation between the youth and entered the scene when the Black youths responded to the glass soda bottle thrown at them by the white youths.

“These negro boys immediately started throwing rocks at the car occupied by the teenagers,” said Officer Cheek in his statement to Birmingham police detectives. “We backed up about three feet and went around the cars in front of us.”

Teens scatter and run

“Here come the police! I ain’t going to jail!” yelled Lorenzo McCall after seeing the police car come toward him, according to his statement to the FBI.

“When they saw us, they broke and ran,” said Officer Haynie in his statement to Birmingham police detectives.

The three teens – Lorenzo McCall, Doug McCall and Johnnie Robinson – ran north on 26th Street North and then turned left into 8th Alley, running west into the alley.

Ernest Jones and William Gunn also ran on 26th Street North, but went past 8th Alley about a half block north.

Doug McCall ducked into the entrance of an apartment building on 8th Alley so that he was out of the view of the police officers.

Howard King, 20, saw Lorenzo McCall and Johnnie Robinson run past him at about 4:00 p.m. He was sitting on the front steps of his apartment building on 26th Street North and 8th Alley Court, according to his statement to the FBI.

The police car drove onto the sidewalk of 26th Street North because the entrance to the alley was too narrow.

“When they went in the alley, I cut down the sidewalk and applied my brakes at the alley because I could not turn into the alley,” said Officer Cheek in his statement to Birmingham police detectives. “I was in the process of mashing the brake and getting the car to a stop and it slid about three feet.”

Holding his shotgun out of the rear window of the car, Officer Jack Parker aimed in the direction of where Johnnie Robinson and his two friends had run to on 8th Alley.

“Mr. Parker had the gun out the window,” said Officer Haynie about Parker’s unsafe use of the firearm in his statement to Birmingham police detectives.

At least two shots rang out, according to witness statements.

Lorenzo McCall heard the gunshots and saw what he thought was a bullet whiz past him.

Pellets from the shotgun blast hit Johnnie Robinson in the back.

Johnnie Robinson fell forward on the ground. He got up and tried to run, but fell again and lay on the ground, according to Officer Cheek’s statement to Birmingham police detectives.

Lorenzo McCall kept running, jumped over a wall, and then entered an open window in one of the apartment buildings. He hid in the basement, according to a statement he gave to the FBI.

After the shooting

“Get the hell in the house!” yelled one of the policemen to Howard King, who had just witnessed the shooting, according to the statement King gave to the FBI.

King immediately got up from where he was sitting outside and went into his apartment building, where he stayed for the rest of that day.

From the basement window, Lorenzo McCall peered out to see whether the police officers were gone so that he could leave the building, according to his statement to the FBI.

Lorenzo McCall saw a police officer walk over to where he was hiding and look into the window, waving a flashlight. He stood still to avoid detection by the police officer and saw that the police officer had a long gun, likely Officer Parker with his shotgun.

The police officer did not see Lorenzo McCall and walked away from the window.

Then the police officer walked over to Johnnie Robinson, who was lying face down on the ground, placed his foot on Johnnie Robinson’s side, and pushed the body over.

“This ***** is dead,” proclaimed the police officer using a racial epithet, according to Lorenzo McCall’s statement to the FBI.

FBI special agents in Birmingham

FBI Special Agents John W. Culpepper and John C. Newsome happened to be driving around in northeast Birmingham when they heard gunshots.

They drove to 26th Street North and saw a Birmingham police officer standing in 8th Alley and offered their support. The officer responded no, that he’d already called for assistance.

Culpepper and Newsome saw Johnnie Robinson lying on the ground. They noted in their report that he was “still breathing at that time.”

They saw several white youths walk over to the police officer who asked if they were the youths who’d interacted with the Black teens.

After responding yes, the white youths agreed to go to the police station and provide statements, according to an FBI report.

Family dinner disrupted

At around the same time as the shooting, Johnnie Robinson’s aunt, Daisy McConico, 53, asked Leon and Dianne Robinson to take the dinner she’d just cooked to their mother. When they arrived, no one was home, recalls Leon Robinson.

Leon Robinson stayed at the house and his sister Dianne Robinson went to find her mother and found her very upset.

Martha Robinson had left the house to walk down the street because she heard that someone had been shot. She arrived to see her son Johnnie Robinson on the ground, but police officers denied her request to see her son.

Martha Robinson and her daughter Dianne later told Leon Robinson that they went to Hillman Hospital to find Johnnie Robinson lying on a gurney in the hallway.

Hillman Hospital records indicate that Johnnie Robinson was dead when he arrived at the hospital.

However, his mother and sister told Leon Robinson that they believed that Johnnie Robinson was still alive when he arrived at the hospital and was waiting in the hallway to be attended to by doctors although he was in critical condition.

When the doctors did attend to Johnnie Robinson, they pronounced him dead.

Martha Robinson left the hospital screaming at police officers that they’d killed her son, recalls Leon Robinson about what his sister Dianne told him.

Birmingham Police investigate

Two hours after the shooting, Birmingham police detectives initiated an investigation into the officer-involved shooting.

Detectives Charles L. Pierce, and M.E. Gullion began by interviewing all four police officers in the car. Jefferson County Coroner Dr. Joe O. Butler sat in on all the interviews.

“I hollered for them to stop when they got up the alley and then I shot at the ground at their feet, and just as I shot, this one boy fell down,” said Officer Parker, according to his statement to police detectives.

Early news articles reported on what Birmingham police told them, stating that Johnnie Robinson ignored orders from police officers to halt.

Officers Cheek and Haynie did not initially say that Parker gave a verbal warning. They responded yes specifically when asked, appearing to be prompted to answer in the affirmative.

Officer Chadwick did not say that Parker gave a verbal warning prior to firing the shotgun.

“Just as we got to the alley – the sidewalk was very rough – we hit a bump and the gun went off,” said Officer Chadwick in his statement to police detectives.

National police expert Ron Hampton, Executive Director of the National Black Police Association, in a telephone interview in February 2025, advises that the gun would not have gone off unless the police officer had his finger on the trigger, a highly dangerous practice according to law enforcement standards.

“Officers are trained to keep their finger off the trigger,” says Hampton.

Birmingham police detectives interviewed all seven white youth in the red and white 1954 Ford automobile. None of the white teens in the car saw the shooting, according to their statements.

The Birmingham police investigation was sparse. They did not interview Johnnie Robinson’s friends — William Gunn, Ernest Jones, Lorenzo and Doug McCall — who were with him that day. Nor did they interview neighborhood witnesses who saw the shooting, such as Howard King, even though a police officer had spoken with him at the scene.

The Birmingham police did not examine discrepancies between the officers’ statements.

“That police department during that period of time was not looking for the truth when it came to the death of Black people,” says Hampton.

By all indications, the Birmingham police investigation concluded two hours after it had started.

Reverend Oliver calls the DOJ

Later that day, Reverend Claude Herbert Oliver, 38, contacted the U.S. DOJ to alert them about the shooting of Johnnie Robinson and to relay his concerns about the safety of Black residents in Birmingham.

Oliver served as Executive Secretary of the Inter-Citizens Committee, an organization he founded with Reverend Fred L. Shuttlesworth and other several Black ministers, to document police abuse in Birmingham.

Staff from the U.S. DOJ’s Civil Rights Division returned Reverend Oliver’s call at 7:50 p.m., according to an FBI teletype.

“He said he knows local police, as well as the Highway Patrol, will not protect Negro citizens,” relayed an FBI teletype about Oliver’s conversation with U.S. DOJ officials.

The FBI teletype notes that Oliver voiced concerns about the differential treatment of Black children by law enforcement and that he requested that President Kennedy send federal troops to protect Black residents of Birmingham.

Oliver said that he wanted to be sure that an autopsy on Johnnie Robinson was conducted before the burial, presumably to ensure that accurate details on how he died could be determined.

Parker, Jack and Johnny Brown Robinson Shooting Investigation File, 1963, (File #1843.1.1, Federal Bureau of Investigation Files, Birmingham Public Library, Department of Archives and Manuscripts)

Preliminary U.S. DOJ investigation

In response to Reverend Oliver’s request, John Murphy of the U.S. DOJ’s Civil Rights Division asked the FBI to conduct a preliminary investigation into Johnnie Robinson’s death to determine if there was sufficient evidence to conduct a full investigation, according to an FBI memorandum.

FBI Special Agents John T. Downey, and C.B. Stanberry, started the preliminary investigation the next day at Hillman Hospital to examine the hospital’s records and the death certificate.

Downey and Stanberry then went to the Smith & Gaston Funeral Home at 16th Street North and 5th Avenue North to verify the details of how Johnnie Robinson died. They inspected his body and confirmed what the hospital records and death certificate stated, that he died from gunshot wounds to the back of his chest.

FBI Special Agents notified Birmingham Police Chief Jamie Moore of their investigation. Moore responded that he “did not desire to furnish any information concerning the facts in the case,” according to an FBI memo.

However, Birmingham Police Detective Charles L. Pierce did provide the names of the officers involved in the shooting to Downey and Stanberry.

FBI Special Agents sought to interview Officer Jack Parker, but he responded that he’d already spoken to his superior officer and would not make a statement to the FBI.

Esso manager Charles Angelo shared what he saw but informed agents that he did not want to sign his statement or be called on to testify. He felt it would negatively impact his business, and did not want to be involved in what he considered to be a controversial matter, according to his interview with the FBI.

Howard King also witnessed the shooting and spoke with FBI Special Agents. He revealed that he’d observed the entire shooting and did not hear Parker give a verbal warning before shooting Johnnie Robinson. He also disclosed his interaction with one of the police officers. He declined to sign the statement.

Johnnie Robinson’s friends Doug and Lorenzo McCall met with FBI Special Agents to discuss what they’d witnessed. Both refused to sign their statements.

Stanberry issued a brief internal report summarizing the interviews with witnesses, dated September 20th, according to FBI records.

“They feared for their safety because the FBI wasn’t going to be there for the rest of their lives,” says national police expert Ron Hampton about the possible reasons why the witnesses did not want to sign their statements. “The Birmingham police were going to be threatening and intimidating.”

City council calls for full disclosure

The day after the church bombing and the shootings, Birmingham City Councilman Dr. Eleazor C. “Doc” Overton, 44, called for a full disclosure of the killings that day.

“Details of the shootings should be made public so any misinterpretation will be straightened out,” stated Overton in a written press release.

In making the statement, the city council was likely unaware that the Birmingham Police investigation was already over and could not have anticipated that the details would not be made public for years.

Coroner’s report

Five days after the shooting, Jefferson County Coroner Dr. Joe O. Butler issued a report stating that Johnnie Robinson had been killed by shotgun pellets.

According to the death certificate, he was “struck by shotgun pellets by [a] police officer” at 4:40 p.m. and died within 15 minutes.

Butler listed the cause of death as a “gunshot wound of chest (back).”

However, the coroner’s report was unresolved on whether the shooting was accidental or not.

“Some testimony shows that Officer Parker’s gun was fired accidentally as the police car slid to a stop,” Coroner Butler stated in his report. “Also some testimony shows Officer Parker fired while performing his duties as a patrolman for the city of Birmingham.”

To reach a decision, Butler asked Circuit Court Solicitor Emmett Perry, 64, to place the case on the docket for the Jefferson County Grand Jury.

Subsequent news articles in the days following the shooting noted the conflicting statements among the police officers on whether Officer Parker gave a verbal warning before firing his shotgun.

Funeral program cover and inside. (Courtesy of Leon Robinson)

Funeral

“Every negro mother’s son is a potential Johnnie Robinson,” said the Reverend Abraham Lincoln Woods, 36, one of the founders of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, at the funeral services on September 22, 1963, according to press reports.

Speaking before hundreds of mourners at New Pilgrim Baptist Church, in his eulogy, Reverend Woods said that, “Birmingham has a long, despicable record of police brutality.”

Reverend Norman “Jim” Jimerson, 40, a white minister who headed up the Alabama Council on Human Relations, formally participated in the funeral service by offering prayers. Jimerson was one of the only white people to attend the teen’s funeral, according to press reports.

Johnnie Robinson’s friends, William Gunn and Ernest Jones, who were with him the day he died, served as pallbearers, along with three others.

The name on the funeral program and the headstone read “Johnnie” Robinson, spelled the way his parents named him. Subsequent news articles continued to incorrectly spell his name as “Johnny,” possibly due to information from police accounts, which had misspelled his name.

His family arranged to bury him at Grace Hill Cemetery, five miles from his home.

Birmingham chief of police won’t cooperate

Staff from the White House asked the U.S. DOJ’s Civil Rights Division about the status of the investigation, specifically inquiring about whether Birmingham Police Chief Jamie Moore would make statements by Officer Jack Parker and the other three police officers available to the FBI, according to an FBI teletype dated September 30th, 1963.

A couple of days later, Moore told the FBI, when they requested the file for the second time, that he would not make the file available. Moore explained that he didn’t want to share any information with the FBI before the upcoming meeting of the Jefferson County Grand Jury, where members would consider the evidence and make a decision on whether or not to indict Officer Parker.

While it was not legally required for the Birmingham Police Department to turn over their investigatory file to the FBI, it was customary practice for law enforcement agencies to share information when requested by the FBI.

Jefferson County Grand Jury issues decision

It is not known what evidence was shared with the grand jury or who served on it, as grand jury proceedings are not public.

The Jefferson County Grand Jury reported “no bill” on the case on October 11th, dismissing all charges against Officer Parker, according to local news reports.

That meant Officer Parker would face no legal consequences for Johnnie Robinson’s death and would continue to serve as a police officer in Birmingham.

Full US DOJ investigation

On November 6, 1963, Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall, 41, for the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. DOJ, requested a full investigation into the death of Johnnie Robinson. This meant that they would broaden the scope, gather more evidence, and expand techniques utilized in the investigation.

FBI Special Agents Roy M. Osborn and Henry A. Snow began by interviewing the Black teens who were with Johnnie Robinson, who had not yet provided statements.

William Gunn told the special agents that he heard gunshots as the car slid to a stop but he did not see the shooting.

Ernest Jones gave a similar statement.

Both declined to sign their statements to the FBI, seemingly for the same reasons as the other witnesses.

A week later, on November 15, 1963, Birmingham Police Chief Jamie Moore responded to the third request from the FBI that he would not share Birmingham police officers’ statements with the FBI, as he considered the matter closed because the grand jury had issued its decision.

Ten months later, on August 31, 1964, U.S. District Court Clerk William E. Davis reported “no bill” from the federal grand jury on the case, which meant that all charges against Officer Parker were dismissed.

The aftermath

The Robinson family did not file a civil suit against Officer Parker, as it would be unlikely that they could achieve success after the grand jury’s decision. Civil suits were not a common practice at the time.

Nor did the Birmingham Police Department provide a financial settlement or support to the Robinson family, according to Leon Robinson.

After living through so many traumatic events, Martha Robinson entered a residential treatment facility to receive mental health care, according to Leon Robinson.

Leon Robinson and his sister Dianne Robinson continued to live with their aunt, Daisy McConico, during the school year and in the summers stayed with relatives in New York because their mother was afraid that they could be killed also.

Officer Parker, who headed up the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge #1, signed a newspaper advertisement during the fall of 1963 opposing the integration of the police force, according to press reports.

With no consequences for his actions in shooting Johnnie Robinson, Officer Parker was able to work at the Birmingham Police Department for another decade and retired after 25 years on the force in 1973. He died in 1977.

FBI opens new investigation

On April 16, 2007, the FBI opened a new investigation into Johnnie Robinson’s death, under the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Act (P.L. 110-344), which provided for investigations of civil rights crimes that resulted in a death before December 31, 1969.

The FBI’s new investigation appears to draw exclusively from the scant 1963 Birmingham police investigation in which only the four white police officers and the white teens in their 1954 Ford were interviewed.

The U.S. DOJ’s memo on the case does not mention its own previous investigations in 1963 that included the witness statements to FBI Special Agents from Johnnie Robinson’s friends and neighbors. The memo also does not reference the 1964 Federal Grand Jury proceedings.

During the FBI’s new investigation, Johnnie Robinson’s siblings requested copies of the FBI’s files on the case in 2009.

The FBI closed the case on April 28, 2010, as they determined that Parker had died in 1977. The memo states that, “This matter lacks prosecutive merit and should be closed.”

Leon Robinson and his sister Dianne (who married and changed her last name to Samuels) received copies of the FBI’s files and an FBI agent visited with them to advise on their brother’s case closure.

“We were very surprised to hear from the Justice Department,” recalls Leon Robinson. “We thought they were going to sweep it under the rug.”

While the Robinson siblings were pleased to receive the files and learn that the FBI had conducted an extensive investigation in 1963 on their brother’s case, they still didn’t feel that justice had been achieved.

“We couldn’t get no justice,” says Leon Robinson.

Remembering Johnnie Robinson

Johnnie Robinson is remembered in some notable places in Birmingham.

The city of Birmingham included him in the Gallery of Distinguished Citizens in City Hall in 2012.

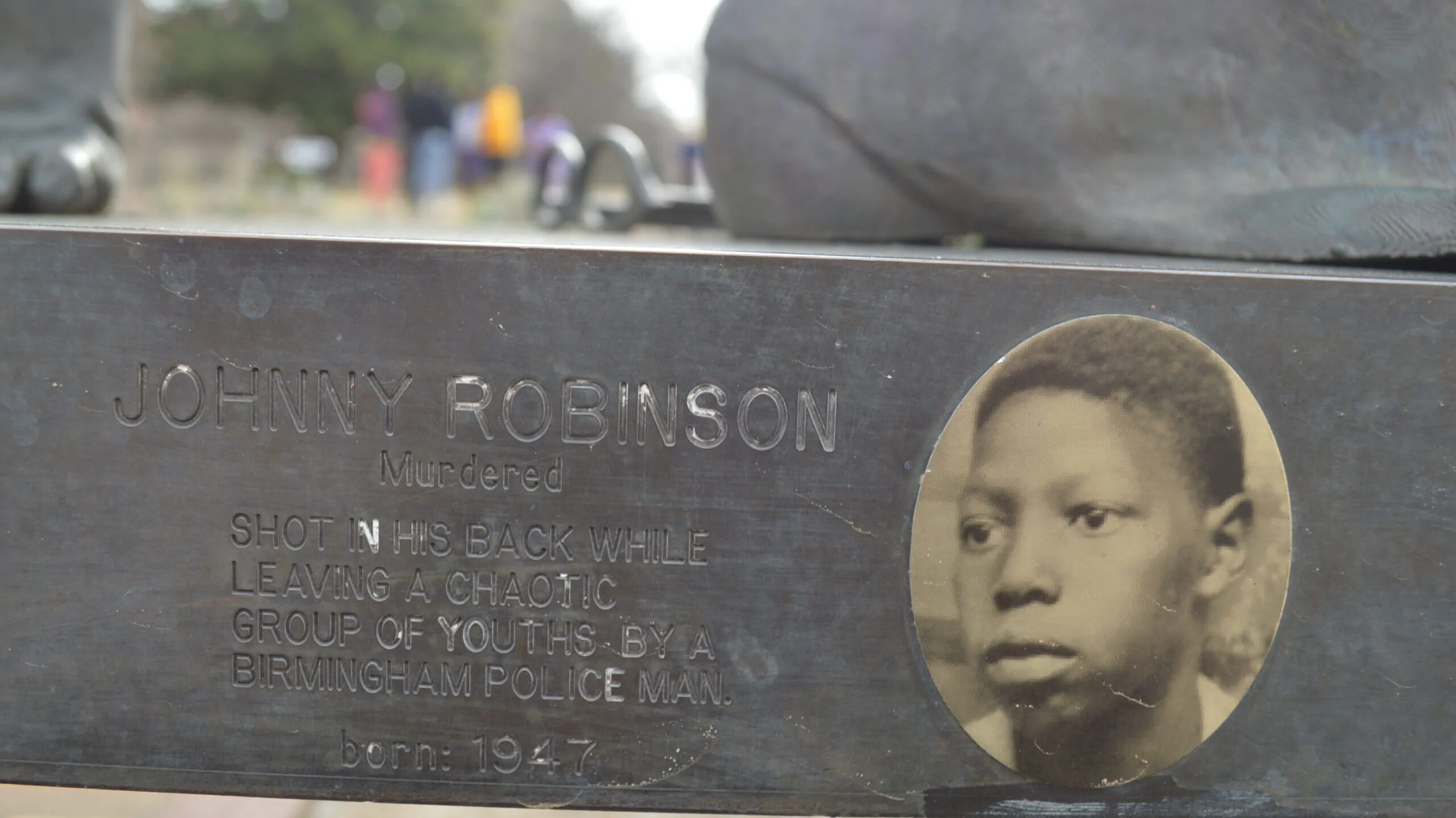

His photo is on the bench of the Four Spirits sculpture, created by world-renowned sculptor Elizabeth MacQueen, at Kelly Ingram Park in Birmingham in 2013.

The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute includes Johnnie Robinson in its permanent exhibit.

Birmingham City Walk mentions him in their online civil rights history of Birmingham.

“I wish that my mother could have seen all of this,” says Leon Robinson about the commemorations in the city of his brother. Martha Robinson died in 1991.

In other ways, traces of Johnnie Robinson’s life are not so visible.

The home where he grew up on 28th Street North has been torn down. A warehouse stands there.

The church, New Pilgrim Baptist Church, where his funeral service was held, once led by civil rights leader Fred L. Shuttlesworth, is no longer there. A historical marker about the church stands on an empty lot of grass.

The street, 8th Alley, where Officer Jack Parker shot Johnnie Robinson, no longer exists. It is now a parking lot for city vehicles.

There are no markers indicating where Johnnie Robinson lived or was killed. Johnnie Robinson is not mentioned in the Alabama Department of Education’s social studies curriculum.

Matt Nesbitt, who grew up in nearby Shelby County, was not familiar with the story of Johnnie Robinson, and that he was killed on a street near where Nesbitt works.

“Just knowing that fact makes you think,” says Nesbitt when the information was shared with him in May 2025 during an interview across the street from where Officer Parker shot Johnnie Robinson.

Lisa McNair, younger sister of Denise McNair, who died in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, believes that Johnnie Robinson’s story is still largely unknown.

“So many people still don’t know his story,” says McNair, who serves on the board of the Morgan Project, in an interview by telephone from her home in Birmingham in May 2025.

McNair, who recently authored Dear Denise: Letters to the sister I never knew is asked to give talks about September 15, 1963, regularly.

“I always include Johnnie Robinson and Virgil Ware in my presentations,” says McNair.

Reverend Norman “Jim” Jimerson’s daughter, Ann Jimerson, 74, who founded the Kids in Birmingham 1963 nonprofit organization to share the stories about what happened in Birmingham on September 15, 1963, says that Johnnie Robinson and Virgil Ware are often left out of the narrative.

“I feel that most people who hear the story about the girls do not know about the deaths of the two young men,” says Jimerson in a telephone interview from her home in Washington, DC, in April 2025. “I do think that getting them into the curriculum so that people grow up, at least the people in the area, knowing that this was part of it.”

Johnnie Robinson on Four Spirits sculpture by Elizabeth MacQueen in Kelly Ingram Park. (Liz Ryan)

Cherishing the memory of his brother

More than 60 years later, Leon Robinson is the only surviving sibling of Johnnie Robinson.

“If I’d have been with him, I probably wouldn’t have been here neither,” says Leon Robinson. “But God had other plans for me.”

Since 1963, Leon Robinson has experienced a lot, including being drafted by the U.S. Army to serve for a year in the Mekong Delta during the Vietnam War and raising 8 children.

He spends his time these days with his growing family, which now includes 25 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

He smiles when he thinks of the good times with his older brother Johnnie Robinson when they were children.

“He was always a lot of fun,” says Leon Robinson.