On Thursday, August 7, a panel of three district court judges in the Northern District of Alabama issued an injunction in the voting rights case Milligan v. Allen requiring Alabama to use its current Congressional districts until new maps are drawn based on the 2030 Census. The court will also retain jurisdiction over the case until the injunction expires.

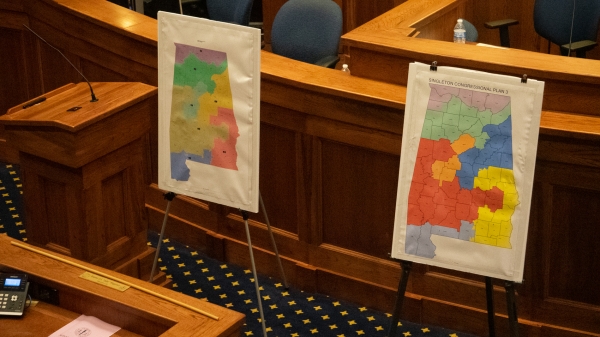

Selected by a federal court in 2023, after Alabama’s state legislature repeatedly failed to adopt district maps acceptable under the Voting Rights Act, the current maps enabled the election of Democratic Congressman Shomari Figures to represent the state’s 2nd District last year.

The panel declined, however, to place Alabama back under preclearance. Under Section 3(c) of the Voting Rights Act, being placed under preclearance would have prevented the state from altering voting practices unless the court ruled a proposed change “does not have the purpose and will not have the effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race or color.”

“Although the Court declined to restore preclearance review, we are excited that the Court ordered Alabama to continue using the special master map through 2030,” the plaintiffs wrote in a joint statement on Friday. “This independently drawn map respects Alabama’s many communities of interest, including the Black Belt, and ensures that Black voters will continue to have a fair opportunity to elect congressional candidates of their choice.”

In an over 500-page injunction and order issued earlier this year, the panel of judges declared that the legislature’s attempt to adopt another plan without a required Black opportunity district after the first plan was ruled likely to be discriminatory “amounted to intentional racial discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection guarantee.”

“Congress designed Section 3(c) as a backstop ‘to insure against the erection of new discriminatory voting barriers by States or political subdivisions which have already been found to have discriminated,’” the plaintiffs’ lawyers accordingly argued in a recent filing defending their request for preclearance. “That is precisely the risk here given Alabama’s conduct during this redistricting cycle.”

The legal counsel for Wes Allen and the other defendants, however, responded in part by saying that “there is no need for the extraordinary remedy of preclearance where litigation has proven adequate to prevent the use of the plan this Court found to be intentionally dilutive.”

A statement of interest of the United States additionally contained the argument that “a single violation of the constitutional right to vote cannot suffice [to qualify for Section 3(c)], or it would make it possible for every case of alleged intentional discrimination to be bailed into coverage.”

In the order accompanying Thursday’s jurisdiction, the judges explained their reason for issuing an injunction requiring the use of Alabama’s current districts while not placing the state under preclearance again.

“We have no doubt that the remedial rulings we have entered fully redress the constitutional and statutory violations we have found. We do no more than enter a remedy designed to restore the victims of discriminatory conduct to the position they would have occupied in the absence of such conduct,” they wrote. “Accordingly, we decline at this time and on these facts to bail Alabama back into federal preclearance.”

On July 29, when plaintiffs argued that the court should consider requiring preclearance, member of the panel Judge Terry Moorer responded that he was “hard-pressed to understand.” He added that the court needed to “tread very lightly, as far as the legislature has a role to play that the court cannot play.”

The defendants already appealed the initial May injunction to the Supreme Court in June. The state and plaintiffs will both have to submit briefs on whether the case should be heard for the third time by the Supreme Court in the next few months.