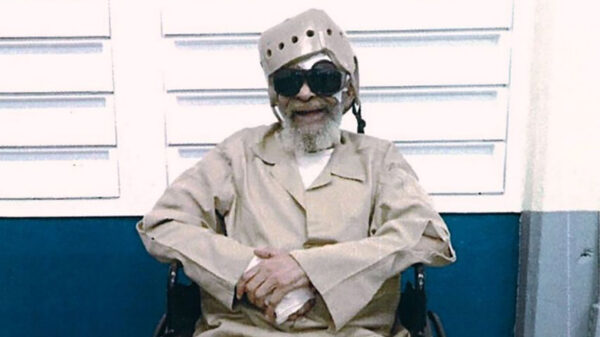

Early in the morning of March 2, 1998, Louisiana resident Patrick O. Kennedy climbed into his 8-year-old stepdaughter’s bed and so violently raped her that she would later require emergency surgery. At 6:15 a.m., he called his work to say he wasn’t coming in, and at some point before 7:30, he called again, asking a coworker how to remove a bloodstain from carpet. Minutes later, he called a cleaning company and tasked them with the job. He then began the process of coaching the lie that it was two neighborhood boys, heaping psychological trauma and guilt on top of the savagery he had already committed.

At around 9:30 — having left his stepdaughter torn and bleeding for some three hours following what a doctor would eventually call the most severe sexual assault in the four years of his pediatric forensic medicine practice — the monster called 911.

It took eight days of investigation for the lie to fall apart, after which Kennedy was arrested on the then-capital charge of aggravated rape of a child. Five years later, 12 men and women speaking for the rest of the state of Louisiana — perhaps standing in the place of anyone with a heart and the very reasonable, unquenchable human outrage at what Kennedy did — sentenced him to death.

On appeal to the United States Supreme Court, Kennedy did not argue he was innocent; the evidence was far too damning for that. Rather, he and his attorneys contended that the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment forbid the imposition of the death penalty for a crime — no matter how heinous — that did not take the life of its victim.

On June 25, 2008, in a 5-4 decision, the Court agreed; despite the inhumanity of his crime, Kennedy could not be put to death consistent with a 21st century understanding of the Constitution and an Eighth Amendment that mandates both a limited and proportional application of the death penalty.

Now, some 20 years later, Kennedy v. Louisiana remains good law, meaning that the death penalty is still confined to the limited cases of murder that we deem worthy of an ultimate, irrevocable punishment. But with the sordid, terrible allegations and arrests coming out of Bibb County and the political calendar pushing politicians to once again consider the death penalty for child rape, it’s worth reexamining the Court’s reasoning in Kennedy and considering why it remains correctly decided.

At its core, Kennedy is built on “evolving standards of decency” (a phrase designed to stop a constitutional originalist’s blood cold) as seen through a line of cases that limited the application of the death penalty to either certain crimes or prevented its use against certain types of defendants.

These cases began in 1977 with Coker v. Georgia, a badly fractured decision in which anti-death penalty Justices William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall joined with others on the court to find that Georgia’s death penalty for the rape of an adult woman was unconstitutional; yet the justices together could agree on little more than the outcome.

Five years later in Enmund v. Florida, the Court limited the use of the death penalty in cases of “vicarious felony murder,” finding that it was unconstitutional in cases in which a defendant voluntarily participated in an inherently dangerous felony but did not kill, intend to kill or intend to use force. (In Enmund, the defendant was a getaway driver for a robbery who had no notice of the plan to kill two elderly victims during the theft.)

Finally, only a few years before Kennedy was decided, the Court found it was unconstitutional to execute both mentally disabled defendants (Atkins v. Virginia in 2002) and those who were juveniles at the time of the crime (Roper v. Simmons in 2005).

These cases also stand on Gregg v. Georgia and four other decisions handed down on June 2, 1976, a day which marked the end of a four-year moratorium on the death penalty in America and began a new era in which capital punishment had to be administered in limited and controlled ways. In both Woodson v. North Carolina and Roberts v. Louisiana, two of the five “Death Penalty Cases” along with Gregg, the Court found the death penalty could no longer be a mandatory punishment; juries had to have discretion in the punishment handed down, but that discretion had to be reasonably channeled. As Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for the majority almost 30 years later in striking down Louisiana’s child rape death penalty, “When the law punishes by death, it risks its own sudden descent into brutality, transgressing the constitutional commitment to decency and restraint.”

Generally, that restraint in the law is achieved by limiting the types of murders eligible for the death penalty and separating capital trials into a guilt/innocence phase and subsequent punishment mini-trial in which statutory aggravators and mitigators are considered. In Alabama, Sec. 13A-5-40 sets out 21 different examples of homicides that are eligible for the death penalty, whereas 13A-5-49 outlines the aggravating factors in a murder that could push a jury to sentence a defendant to death. The system is not perfect and circular at times (for example, murder for monetary gain is one of the specified capital crimes and also one of the statutory aggravators), but it is a system we have built through 50 years of policy experimentation and court decisions.

And importantly, while our state’s politicians have traded in their business suits for lab coats and experimentation with novel methods of execution, even in Alabama, the death penalty policy system has tended toward more restraints, not fewer. In addition to the above-mentioned Supreme Court decisions, one of the first bills signed into law by Gov. Kay Ivey after coming into office in 2017 was legislation that ended judicial override in death penalty cases, which meant that judges could no longer unilaterally sentence a defendant to die after a jury voted for life imprisonment instead, and made Alabama the final state to ban the practice.

If Alabama enacts a death penalty for child rape — and if the Supreme Court more implausibly upholds such a choice and expressly overturns Kennedy v. Louisiana — that jurisprudential system will be thrown into chaos. No longer would the most severe punishment be reserved exclusively for certain types of the only crime that forever ends another human life. The punishment phase of trials — assuming in a post-Kennedy world the Court would not overturn the Gregg line of cases entirely — would have to consider an entirely different set of aggravating factors, the majority of which (previous convictions for child rape, age of the victim) seem entirely unsuitable for distinguishing for a reasonable, dispassionate juror the child rapists who should go to death row and those who should remain in prison for the rest of their natural lives.

The final immutable truth is that there is no punishment that would satisfy any normal moral outrage about the rape of a child, just as there is no punishment that could possibly deter an act so grounded in inhumanity. Both the crime itself and our reaction to it are not bound by logic or constrained by reason.

We live in a constitutional democracy — by definition, that comes with restraints on the will of the people, with the Eighth Amendment serving as an important backstop against a slide into the eye-for-an-eye abyss. If Montgomery politicians enact this policy change and the Supreme Court goes along with it, I will not mourn the newly condemned child rapists, because they made an abominable choice and deserve no more pity than they show their victims.

I will, though, give pause at the thought of the law’s slide into barbarism.