In early November 1960, when The Auburn Plainsman editor-in-chief Jim Phillips heard from senior editor Bobby Boettcher about the brutal beating of a local Black man named Forney Calhoun, Phillips knew he had a difficult decision to make. Should he publish the story?

“Boettcher convinced me that he had a solid story, and The Plainsman had a moral obligation to cover the issue,” Phillips wrote in an email from his home in Mt. Airy, North Carolina.

At that time, The Plainsman hadn’t published anything about racial injustices since 1957, when “columnist Anne Rivers was censured by university officials for writing a column criticizing segregation,” Phillips said. “Stories and opinions on racial issues had been unofficially taboo at The Plainsman” ever since.

Phillips faced other pressures, too. An anonymous caller threatened Phillips on the telephone to keep the beating incident out of The Plainsman.

And Phillips wondered whether to consult Auburn University officials.

Phillips sought the advice of Lee County Bulletin founder and editor Neil O. Davis. A recipient of the prestigious Nieman fellowship from Harvard University and President of the Alabama Press Association, Davis was recognized nationally for his progressive stance on civil rights. David did not tell Phillips whether or not he should publish, but appeared to be supportive.

Despite real and potential opposition, Phillips went ahead and published the story and included an editorial as well, without informing university officials in advance, making The Plainsman the first news outlet in Alabama to report the crime.

However, as soon as students delivered the Thursday, November 18, 1960 edition of The Plainsman on the Auburn campus, university officials reacted.

University President Ralph Draughon, along with Student Affairs Director James Foy and Alumni Secretary Joe Sarver, called Phillips and Boettcher into the president’s office. Draughon reprimanded the two students for not consulting university officials before publishing the story.

“The recurrent theme was that we were aggravating an already explosive racial situation and were endangering Auburn’s appropriations from the state legislature,” Phillips recalled. “It was a chilling experience.”

Still, the students persisted. Phillips and Boettcher, along with fellow staffers James Clinkscales, Jim Bullington and James Dinsmore continued to report and editorialize on developments in the story for The Plainsman over the subsequent few weeks. Other outlets followed The Plainsman’s lead, albeit with a more neutral stance.

Calhoun died on November 17, 1960, on the same day as The Plainsman had been submitted for printing, to be published and distributed the next day.

With continued coverage in the press, Lee County Sheriff Eugene E. Lowe charged two men with murder in December 1960: Leonard Hood, 33, an Auburn University public safety officer and part-time deputy sheriff, and his brother-in-law Hershel Berry, 48, an Auburn University employee. Six months later, a Lee County grand jury indicted Hood, but did not indict Berry. A week later, on May 31, 1961, a Lee County Circuit Court jury acquitted Hood.

After the acquittal, Calhoun’s story was forgotten for decades until it was brought to the attention of local leaders.

Without The Plainsman’s coverage, the details of the case would have been largely lost.

Forney Calhoun: 67-year-old African American farmer

Forney Calhoun lived on Wire Road, south of Auburn University. He worked as a farmer.

“We called him Uncle Fonny,” said Napoleon Withers, 68, Calhoun’s grand nephew, in an interview at his home in Kellyton. Withers was only 7 years old when his great-uncle was killed. There were a lot of members of the Ku Klux Klan in the area where they lived in the 1960s, Withers recalled.

Withers remembered walking to church at night with his family when he was a child. When cars appeared to approach from a distance, he and family members hid behind trees until after the car passed to avoid being seen by the driver in the car.

If the driver was a Klansman, explained Withers, “they would come out and beat you.”

Leonard Hood beats Calhoun multiple times, then arrests him

Leonard Hood and Hershel Berry accosted Forney Calhoun on November 4, 1960, by boxing his car in with their cars, according to news reports at that time. A November 2022 Opelika-Auburn News article reported that Calhoun’s niece, Essie Calhoun, recalled that Hood actually drove Calhoun off the road.

All three men lived in the same area south of Auburn, around Notasulga and Tuskegee, Alabama. Hood and Berry were co-workers at Auburn University, as well as brothers-in-law. Hood was married to Berry’s sister, Eva Berry, 33. Berry was married to Hood’s sister, Florence Hood, 43.

Hood pulled Calhoun out of his car and beat him.

Calhoun’s friend and passenger in his car, Sar Townsend, got out of Calhoun’s car. Local papers reported that he ran away. Withers said that he recalls Sar Townsend as a large, 275-pound man who he did not believe could run very fast. Hood beat Calhoun repeatedly in two other locations that day, according to local news reports.

Even though Hood was not on duty as an Auburn University public safety officer, Hood utilized his authority as a deputy sheriff to arrest Calhoun, local news outlets indicated.

The Lee County Sheriff’s Office could not confirm Hood’s employment or status as a Lee County deputy sheriff, as the records were not retained, said Sheriff Jay Jones, who has been with the office since 1975.

Hood and Hershel drove Calhoun to the Opelika Jail and booked him on the charge of intoxication, although his employer and the justice of the peace stated that Calhoun had not been drinking, The Plainsman reported.

Lowe kept Calhoun at the Opelika Jail overnight and released him the next day. During Calhoun’s overnight stay at the jail, Lowe did not provide any medical attention for Calhoun, news reports from the time confirmed. After Calhoun was released, his family sought medical attention for him in Tuskegee and then booked him into Cobb Memorial Hospital in Phenix City.

Calhoun died on November 17, 1960.

Dr. Louis A. Hazouri signed the death certificate, indicating that Calhoun’s death was an “accident” rather than a homicide. Hazouri described on the death certificate that the injury occurred as “patient allegedly beaten up by unknown assailants,” although the attackers were known and witnesses disclosed that the beating took place.

The death certificate claims multiple causes of death. The first four causes, bronchopneumonia, hypostatic pneumonia, arteriosclerotic, and cardiovascular renal disease, are all conditions that typically impact older individuals.

The fifth cause of death listed on Calhoun’s death certificate, cerebral contusion, bilateral mixed subdural hematoma, meant that Calhoun suffered from a brain injury on both sides of his head, and there was bleeding in his brain as a result.

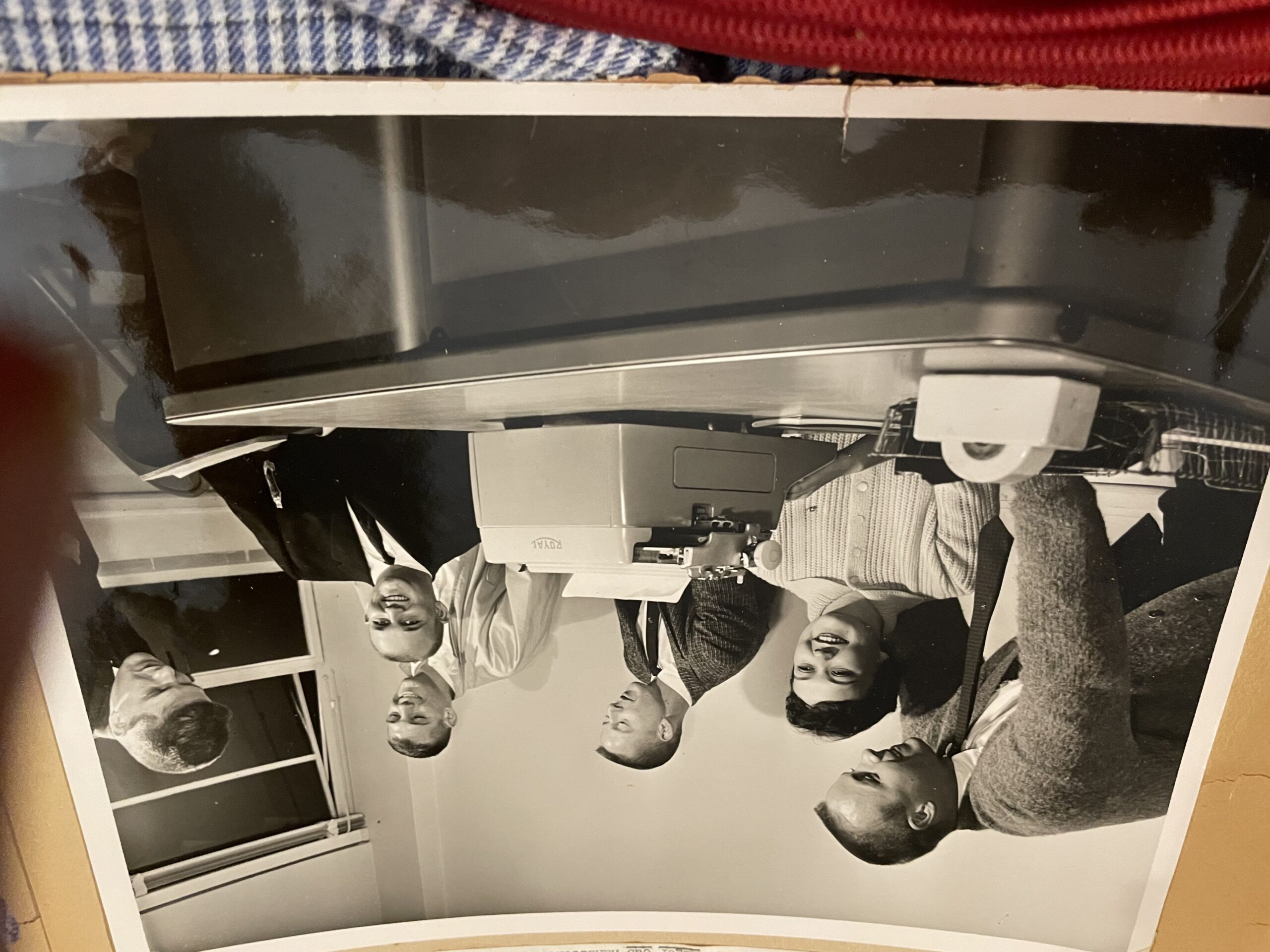

Bobby Boettcher in 1960. (Courtesy of Jim Phillips)

The Plainsman is the first to break the story

“Plainsman reporter James Clinkscales heard about the incident in which Mr. Calhoun was injured and consulted one of our senior editors, Bob Boettcher, about a possible story,” Phillips, then editor of The Plainsman, said. “Boettcher was the primary reporter, and I remember Clinkscales did a lot of the initial reporting.”

Phillips decided not to ask the university for permission to print either an article or an editorial about Hood’s beating of Calhoun. “I feared they would order us not to run it,” he said.

However, Phillips did consult with Neil O. Davis, a previous editor of The Plainsman who’d founded the Lee County Bulletin in 1937, serving as its editor. Davis printed The Plainsman and provided space for the student staff to work out of the Lee County Bulletin offices. That led to an unofficial mentorship by Davis of Phillips, as well as other Auburn student reporters.

Phillips decided to go ahead with publishing after speaking with Davis, recalling that Davis didn’t tell him whether or not to publish the article.

The Plainsman article, “AU employees maul man, escape cause of justice,” ran on November 18, 1960, detailing Hood’s beatings of Calhoun. The article didn’t mention that Calhoun had died the night before, on November 17, because the paper was already at the printer.

The same edition included an editorial, “Enter Justice!” penned by Phillips. “We are sickened by this instance, appalled that we have been instructed to keep this thing quiet,” the editorial read, which concluded with an urging of action on an investigation.

The article and editorial in The Plainsman were the first in the state to cover the story.

Calhoun’s burial, sheriff’s arrests

Calhoun’s family buried him on November 20, 1960, at Rising Star Cemetery in Tuskegee, according to his death certificate.

Sixty-five years later, Withers doesn’t remember if he went to the funeral or not. Withers does recall, however, going to the funeral home with his father to see Uncle Fonny. The funeral home laid out Calhoun’s body on a table before placing Calhoun in a casket.

Withers vividly remembers seeing his uncle’s body, badly bruised from head to toe, at the funeral home.

The following day, Calhoun’s daughter, Julia Mae Williams, accused Hood and Berry of murder, according to press reports. Sheriff Lowe arrested Hood and Berry and charged them both with murder.

Lowe set Hood and Berry free—each on a $2,000 bond. Auburn University suspended the men from employment.

The Plainsman continues reporting, community responds

Two days later, Boettcher penned an editorial, “Sequel – Enter Justice!” The editorial explained why The Plainsman published a front-page article and an editorial the week before.

“We sought to bring to the attention of all Auburn an incident concerning a beating, which warranted a thorough investigation, one which had not taken place at that time,” the editorial read. The editorial noted that The Plainsman conducted its own independent investigation, interviewing multiple people with direct knowledge of the incident, in contrast to some of the other perspectives shared with Lowe, the Lee County sheriff.

“At some point, we added a third reporter, Jim Dinsmore, to the team,” Phillips said. “Jim was a bright and highly motivated reporter who achieved considerable acclaim for his work at The Plainsman over the next several years.”

On the same day, eight ministers in the Auburn community issued a statement raising grave concerns about Calhoun’s death. The ministers called for law enforcement officials to thoroughly investigate. The statement concluded by urging community members to cooperate fully with the investigation.

Auburn ministers Powers McLeod Sr. of Auburn Methodist and Max Hale Jr. of the Wesley Foundation signed the statement. McLeod and Hale were also members of the Alabama Council on Human Relations, an inter-racial organization of faith leaders that sought “to attain, through research and action, equal opportunities for all people of Alabama,” according to the council’s newsletters.

Other signatories to the statement included Fred Barling, Trinity Lutheran Church; John B. Evans, First Presbyterian; John H. Jeffers, First Baptist; Tom Murphy, Westminster Fellowship; Ray Pendleton, Village Christian; and James P. Woodson Jr. of Holy Trinity Episcopal.

Many of these same faith leaders would support Harold A. Franklin, a graduate student, to integrate Auburn University four years later, as detailed in Powers McLeod Sr.’s memoir, Southern Accents, Different Voices.

Auburn student witnesses testify, reporters publish

Two Auburn students who’d witnessed Hood beating Calhoun met with the sheriff’s office to testify about what they’d seen on November 4, 1960. (The Lee County Sheriff’s Office could not provide a record of the witnesses’ statements as the records were not retained.)

A week later, The Plainsman published another story, this time by the paper’s soon-to-be editor, Jim Bullington, who wrote that Hood’s beating of Calhoun and the resulting death of Calhoun had been “a major topic of discussion in Auburn, and has received wide attention around the state.”

Phillips recalled one reaction on campus at an Auburn basketball game. “What I do remember was a loud ‘boo’ from the student section at an Auburn basketball game the week after publication when a uniformed campus police officer—not officer Hood—walked down the side of the basketball court,” Phillips said.

Not all reactions favored The Plainsman student journalists’ coverage. At least one of the student reporter’s family members recalled receiving threatening phone calls after the articles and editorials ran.

Grand jury indicts

In January 1961, a Lee County grand jury was supposed to take up the Calhoun case. However, the court decided not to, explaining very little about why in press reports.

Four months later, Lee County appointed members of the grand jury who would decide whether or not to indict Hood and Berry for the murder of Forney Calhoun. The county appointed a nearly all-white grand jury with the notable exception of one African-American juror, O.W. Corprew, from Auburn.

All-white juries were common in Alabama at the time, as the state’s Jim Crow laws dissuaded African Americans from registering to vote, which meant that they could not then be selected for jury duty since prospective jurors were drawn from voter rolls.

Lee County also appointed to the grand jury two brothers, Emmett Guy Waller, 40, and Ellis Waller, 46, an action not permitted under Alabama law. (The statute also states that an indictment or verdict by a grand jury that includes a disqualified member, e.g., a sibling of another juror, is invalidated.)

On May 19, 1961, the Lee County Grand Jury indicted Hood for 2nd degree manslaughter. In the indictment, the local press reported that the grand jury statement declared that Hood “unlawfully but without malice or intent to kill, killed Forney Calhoun by negligently striking him about the head with his hands or with a shotgun.”

The press reports on the indictment do not mention the extensive injuries that Calhoun’s grand nephew, Napoleon Withers, remembers seeing all over his great uncle, in addition to the head injuries, at the funeral home before Calhoun’s burial.

Circuit court acquits

A few weeks later, Lee County Circuit Court prosecutor Tom Young Sr. argued the prosecution’s case against Hood in court for most of the day. Late in the day, on May 30, 1961, the circuit court jury met for about an hour and at 4:30 pm announced their decision to acquit Hood.

Tom Young Jr., 71, who was 7 at the time his father argued the case, doesn’t recall his father telling him about the details.

“He didn’t talk about cases with his kids,” Young Jr. recalled about his father, who served as a prosecutor for nearly four decades. “Prosecutors don’t usually talk about cases they don’t win.”

The Calhoun family moves away

After Withers’ great uncle’s death, the Calhoun family didn’t talk much about what happened.

“They didn’t want to talk about it in front of the kids,” Withers said.

Withers said his family buried Calhoun at Rising Star, a cemetery off Wire Road near the truck stop at Route 85.

But he couldn’t recall exactly where in the cemetery Calhoun is buried. There’s no headstone, and Withers said no family members know where Calhoun is buried. Withers said often a rock would be placed on the gravesite where someone is buried, and that might be what the family did on his great uncle’s grave.

Withers has lived in the Kellyton community off Route 280 between Birmingham and Auburn since 1966. Withers’ family left Auburn abruptly, following an altercation between his grandfather and a white man. After that altercation, his grandparents also left Auburn and moved to Florida.

Few family members are still alive who remember what happened to Calhoun, Withers said. A lot of families left the area around that time, he noted. “They wanted to get the hell away from there.”

Was justice ever achieved?

When asked whether justice was achieved in his great uncle’s case, Withers answered with a firm “no.”

The Lee County Sheriff’s Office has no record of its investigation of Leonard Hood and Herschel Berry, Jones, the current sheriff, said in a telephone interview. The Lee County Circuit Court clerk’s office did not respond to requests for records on the case.

There is no evidence that the FBI ever investigated the death of Forney Calhoun in the 1960s or later, after the FBI reopened old civil rights era murder cases under the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Act of 2008.

U.S. Department of Justice officials could not be reached for comment on why the FBI did not include Calhoun’s case on their list of cases.

With few known living witnesses, court records or sheriff’s investigative reports, it is unclear why Leonard Hood beat and ultimately killed Forney Calhoun.

However, one entity is looking into the death of Forney Calhoun: the Lee County Remembrance Project. LCRP is a volunteer-based, community-driven initiative working to reconcile the racial violence that uses a truth and reconciliation framework to confront the history of racial terror and engage in the discussions necessary to overcome its persistent legacy, according to its website.

Co-director Ashley Brown, and Sara Driskell, an LCRP board member, shared their goals for the project. “We really want to bring recognition to the people, the communities and the families who went through these experiences in a respectful and as complete a version as possible,” Driskell said.

Brown said that for some people, the information the LCRP shares about cases they look into may be perceived as new.

“Maybe this is the first time they’ve heard it,” Brown said. “Perhaps their parents or their grandparents told them a different narrative.”

To date, the LCRP’s investigation into Calhoun’s death has included gathering newspaper clippings from 1960 and 1961 and reaching out to Calhoun family members. LCRP acknowledged the critical role of the Auburn journalists in initially covering the case and continued coverage, keeping Calhoun’s death in the spotlight.

“It seems pretty clear that this case wouldn’t have gotten as much attention as it did without student journalists taking it up and taking charge,” Driskell said.

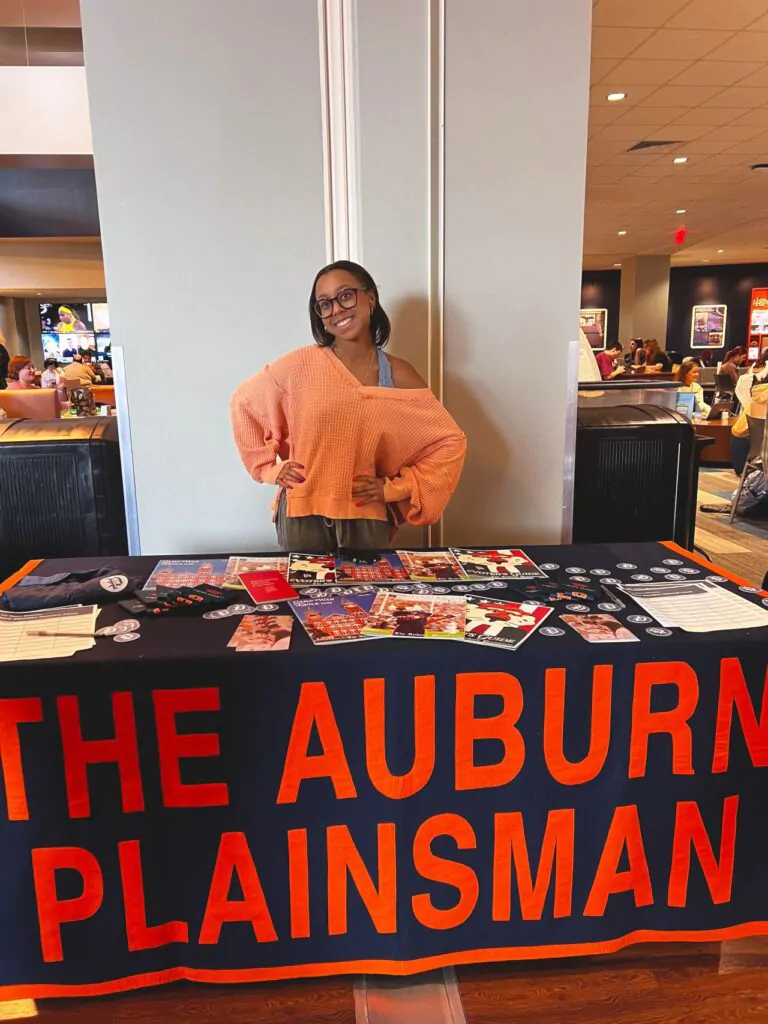

Brychelle Brooks, editor of The Plainsman 2025-2026. (Courtesy of Brychelle Brooks)

The Plainsman today

Since Lee County acquitted Leonard Hood of manslaughter in the death of Forney Calhoun in 1961, Auburn students have continued to publish The Plainsman. The Plainsman’s current editor is Brychelle Brooks, 21, a senior at Auburn University.

“Our slogan is ‘A spirit that is not afraid,’” Brooks said in an interview at a coffee shop in Auburn. “We’re not afraid to put the story out.”

Brooks loves her work at The Plainsman and feels that the paper is for Auburn students by Auburn students.

After learning about The Plainsman’s journalists’ actions in 1960 and the fact that The Plainsman was the first news outlet in the state to report on Calhoun’s beating, Brooks said she takes pride in the Auburn students’ actions.

“I think it is very admirable that they were not afraid to keep going, especially on this story, seeing as though it was not right what happened,” said Brooks.

In sharing more details about the story, Brooks reflected on the impact of the story on The Plainsman’s current team.

“It is very inspiring, especially for our writers now. They can look back on something like this and realize that they, too, can have such an impact,” said Brooks, who will graduate next spring and plans to become a full-time journalist.

Jim Phillips and Jim Bullington in 1960. (Courtesy of Jim Phillips)

Reflections on Calhoun’s death, The Plainsman’s coverage

“Fall quarter 1961—my last at Auburn—is when I decided I wanted to become a career journalist,” Phillips said.

After graduation, Phillips became a full-time journalist, working stints at Congressional Quarterly covering key civil rights milestones, such as the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and at The Washington Post. He later became a congressional investigator in the U.S. House of Representatives and then the U.S. Senate. His investigations led to policy reforms, such as changes in health and safety codes for miners.

Phillips said he has no regrets about his decision not to inform university officials before publishing the November 18, 1960, edition of The Plainsman.

“I have never regretted that decision because I know the story would have been squelched given the political atmosphere at the time,” he said.

Phillips recalled The Plainsman’s team’s work on exposing the injustice to Forney Calhoun.

“The Calhoun case and its mishandling by law enforcement was disgraceful and morally repugnant,” Phillips said, “an example of the unequal justice that Blacks in the Deep South faced in the Jim Crow era.”

Looking back on the case 65 years ago, Phillips reflected on the students’ work.

“Boettcher, Clinkscales, Bullington, and Dinsmore did such a good job of reporting it,” he said. “I’m proud that we ran the story.”