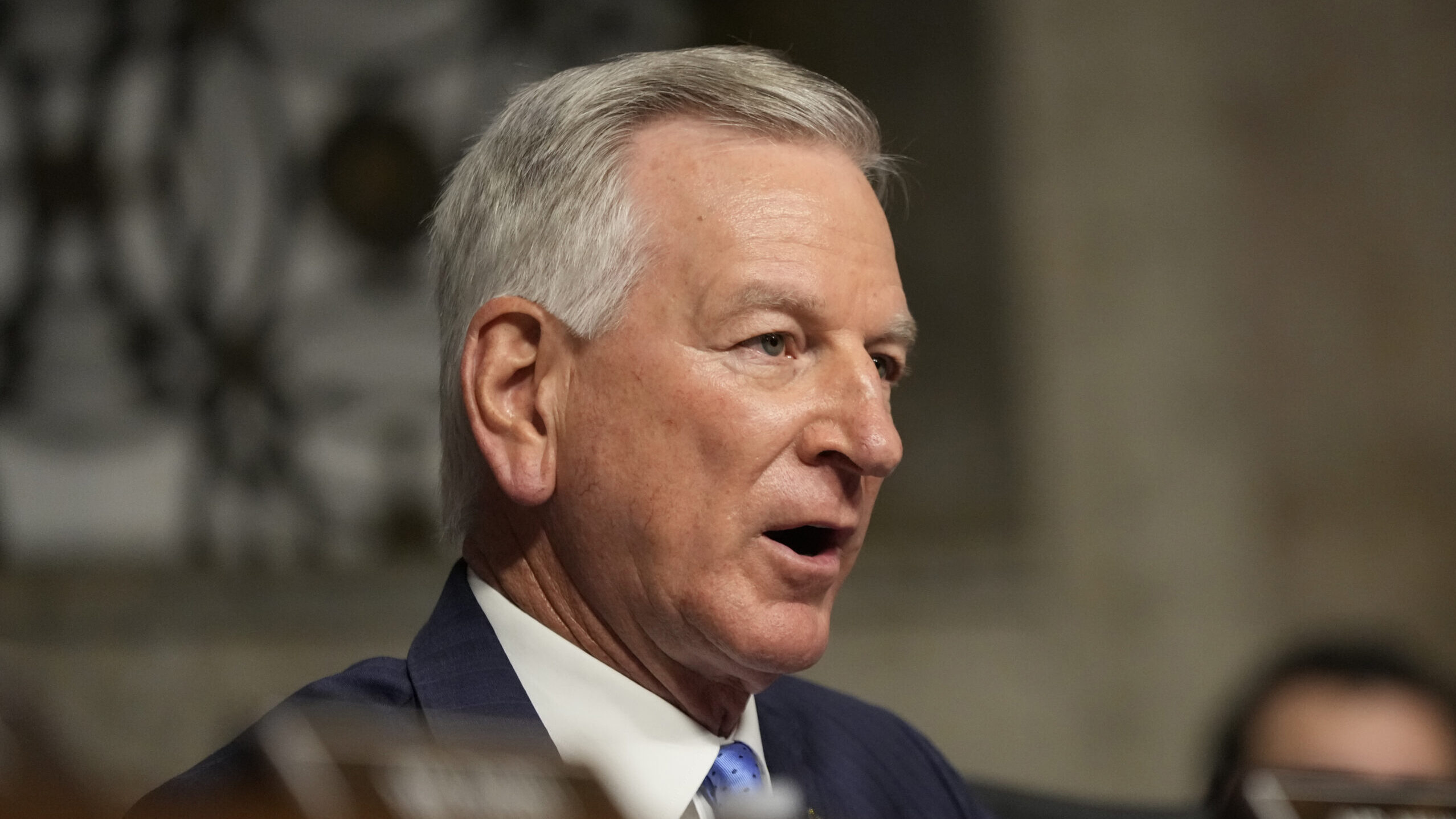

Any ballot challenge questioning U.S. Senator Tommy Tuberville’s residency in his run to be Alabama’s next governor will receive a full review by the Alabama Republican Party, and he will be expected to meet the requirements of the law, several GOP officials told APR. Party insiders say such a challenge is all but certain, raising questions about Tuberville’s residency and fueling unease within the party over his unopposed path to the nomination.

Those with knowledge of internal discussions said the challenge would center on Tuberville’s ties to his beach home in Santa Rosa Beach, Florida. Some of his allies have reportedly dismissed the concern, claiming the party would refuse to hear such a case—a claim senior members say is false.

“The Republican Party will absolutely hear a case if one is filed,” one party insider told APR. “That’s the law and that’s the obligation of the candidate committee.” Under party rules, any formal ballot challenge must be reviewed by the Alabama Republican Party’s Candidate Committee, which is required to conduct a hearing before issuing a decision.

Under the Alabama Constitution, a candidate for governor must have been a resident citizen of the state for at least seven years immediately preceding the election. Over the last several months, Tuberville has been encouraged to demonstrate that he has filed taxes in Alabama during that period to clear up lingering questions about whether his primary residence is the beachfront mansion in Florida—rather than the modest home in Auburn he claims as his Alabama residence.

Under party procedure, any ballot challenge would likely be filed shortly after the qualifying period closes in January, when candidate eligibility is formally reviewed before ballots are certified.

Several legislators are said to be monitoring the issue closely, with at least one considering qualifying for governor in case Tuberville were to be disqualified. “It’s not a likely outcome,” one person familiar with the matter said, “but it’s not impossible either—and some people are willing to take that gamble.”

Even if the challenge fails, Republicans across the state say Tuberville’s approach to the race has left a sour taste. “Sure, he’s going to win—but it’s not healthy for the political process,” one longtime Republican said. “No one should be coronated and not have to answer questions or take a campaign seriously.”

Party members describe Tuberville’s campaign as insular and dismissive. He has declined invitations to speak before local GOP groups, opting instead for closed-door fundraisers. “He acts like he doesn’t have to answer to anyone—not the party, not the voters,” another insider said.

In past cycles, gubernatorial hopefuls crisscrossed the state to win support from county committees and civic groups. Tuberville, by contrast, has kept largely out of public view, frustrating Republicans who say accessibility and transparency are essential to leadership.

Yet the most serious concern surrounding Tuberville’s campaign remains the question of where he has actually lived for much of the past seven years. Multiple reports by news outlets around Alabama and from national media have raised legitimate concerns over whether Tuberville’s true residency is in Florida—particularly after the senator sold off the final Alabama property in his name a couple of years ago. The home he claims as his residence in Auburn—a modest three-bedroom, two-bathroom, 1,400-square-foot house—is actually owned by his wife and son.

Living in Florida and serving as the senator from Alabama is bad optics, but legally not an issue. When running for governor, however, it’s a different story. The former Auburn football coach could largely settle the residency questions by releasing his Alabama state tax returns, but he has so far declined to do so. Once the ballot challenge lands, demands to see those returns—or for Tuberville to otherwise prove he has lived in the Auburn home most of the past seven years—are expected to intensify.

The party has previously enforced its rules in similar disputes. In 2022, several legislative candidates were removed from the GOP primary ballot after the candidate committee determined they had violated party guidelines, demonstrating that the process is neither symbolic nor rare.

Others voiced alarm over claims that Tuberville’s allies have privately said “the judges have our back” should a challenge arise. “Those insinuations are troubling,” a Republican attorney said. “No one should assume special treatment from the courts or the party.”

Even Republicans who once backed Tuberville now question what they describe as an air of entitlement within his circle. “They walk into a room and act like they own the place,” one operative said. “That kind of arrogance might work in Washington, but it doesn’t play well in Alabama.”

One veteran party member called the moment a test of principle. “We don’t anoint leaders in Alabama,” the official said. “We have elections. That’s how democracy is supposed to work—even inside our own party.”

APR reached out to the Tuberville campaign for comment but did not receive a response. Tuberville has not publicly addressed questions about his Florida property or his Alabama residency, nor made any move to prove he has paid Alabama state income taxes—a key point of concern since Florida does not levy a personal income tax.

For many Republicans, the controversy is about more than one candidacy—it’s about whether the party still applies its rules evenly or bends them to protect power. For now, Tuberville’s nomination appears inevitable. But inside Alabama’s ruling party, his unchecked rise has stirred a deeper unease—whether political power without accountability still fits the definition of leadership in a state that once prided itself on it.