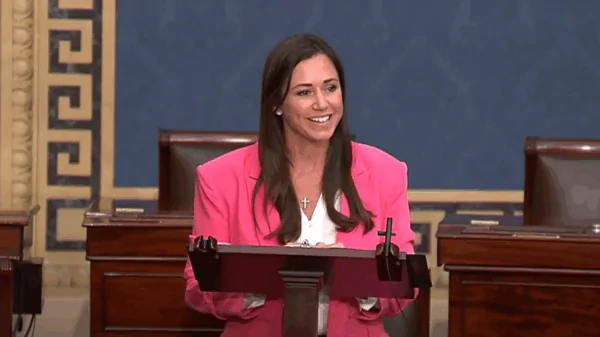

U.S. Senator Katie Britt, R-Ala., is joining Senator Cory Booker, D-New Jersey, to reintroduce the NIH IMPROVE Act, a bipartisan effort to secure long-term federal funding for research aimed at confronting the nation’s maternal mortality crisis.

The legislation arrives at a pivotal moment for Alabama, where lawmakers, health systems and communities continue to face some of the starkest maternal health challenges in the United States.

The latest March of Dimes 2025 report card again designated Alabama with an F for maternal and infant health, citing high preterm birth rates, persistent racial disparities and widespread lack of access to maternity care. The U.S. as a whole received a D+, marking the fourth straight year the organization found the nation trending in the wrong direction.

The proposal would authorize $73.4 million annually for seven years to support the National Institutes of Health’s Implementing a Maternal Health and Pregnancy Outcomes Vision for Everyone Initiative. Created in 2019, IMPROVE investigates the root causes of maternal deaths and pregnancy complications, including targeted studies in underserved and rural communities. But without consistent congressional funding, the program’s work has been vulnerable to year-to-year budget politics.

“I’m proud to fight for moms and women across Alabama and America,” said Britt. “This bipartisan legislation will support targeted funding for critical research to improve health outcomes for women throughout their pregnancy journey.”

Alabama’s maternal health statistics are troubling. The state’s maternal mortality rate, 59.7 deaths per 100,000 births, ranks among the highest in the country. The burden falls hardest on Black women and rural communities, a long-documented pattern that state agencies and advocacy groups have struggled to reverse.

More than one-third of Alabama counties are considered “maternity care deserts,” where pregnant women do not have access to obstetricians, midwives or even basic labor-and-delivery facilities. The trend has worsened as hospitals close or consolidate services; in 2023, three Alabama hospitals shuttered their labor and delivery units.

For Alabama families, that often means driving more than an hour to reach a delivery room, a risk factor for complications and a heavy burden on rural EMS systems. For policymakers, it has become both a political and logistical challenge.

“It’s 2025. These numbers should be moving in the opposite direction,” Britt said during a recent budget hearing with NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya. “Far too many women in this country are dying from pregnancy-related causes.”

The reintroduction of the NIH IMPROVE Act also comes as Alabama lawmakers continue to debate how to strengthen rural health care infrastructure, including maternal care. State officials this year have explored expanding rural residency programs, revising Medicaid reimbursement structures and directing federal pandemic-era funds toward hospital stabilization.

Still, the state lacks a comprehensive, statewide maternal health improvement plan, and county-level capacity continues to decline.

The IMPROVE Act has been endorsed by March of Dimes and the Women’s First Research Coalition, and supporters describe it as one of the few maternal health initiatives likely to garner bipartisan traction in a split Congress. Reps. Underwood and Fitzpatrick authored the House version, noting that IMPROVE has already directed more than $200 million toward maternal health research since 2019, but its continuation depends on stable funding.

“You look at Alabama. We have one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the nation. It disproportionately affects Black women, Native American women, women in rural areas,” said Britt.