When hatred takes hold of the soul, it becomes a killer. It poisons judgment, corrodes conscience, and turns neighbors into enemies. At some point—quietly but unmistakably—hatred became the currency of modern politics, traded for votes, applause, and the power to manipulate fear instead of confront facts.

That reality surfaced plainly this week in Hoover.

On Monday, the Hoover Planning and Zoning Commission voted 7–0 against a proposal that would have allowed the Islamic Academy of Alabama to relocate from Homewood to a vacant office building in Meadow Brook Corporate Park. Formally, the decision was described as a zoning matter. But the rhetoric surrounding the proposal made clear that it was never only about land use. It was about who was asking.

The Islamic Academy of Alabama is a small, private K–12 school serving Muslim families in the Birmingham area. Structurally and legally, it differs little from Christian academies or Jewish day schools across the state. Like those institutions, it exists to educate children within a faith tradition while meeting state academic standards. Its proposal raised the usual municipal questions—traffic patterns, zoning compatibility and long-term planning considerations. Those questions belong properly to city officials.

What government is not authorized to do—at any level—is decide which religions are acceptable or which believers “belong.”

That line matters because it is not merely procedural. It is constitutional.

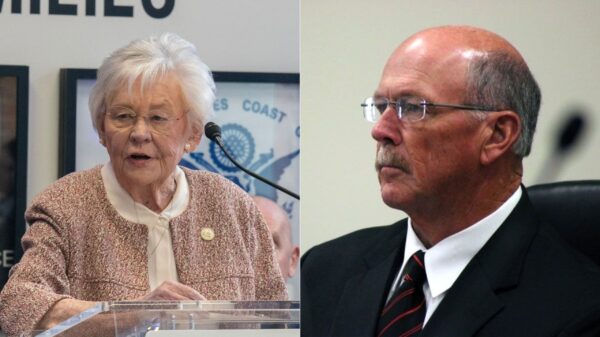

Yet it was openly crossed by U.S. Senator Tommy Tuberville, who is seeking to become Alabama’s next governor. In an interview with Infowars, Tuberville did not engage the zoning issue on its merits. Instead, he portrayed Muslim communities as a national threat, described Islam as a “cult,” warned of “infiltration,” suggested Muslims do not belong in this country, and openly entertained the idea of sending them away. He tied those sentiments directly to his political ambitions and his future use of power.

This rhetoric rips at the fabric of the United States Constitution.

Again and again, history shows what follows when religious belief is transformed from a matter of conscience into an instrument of political power: violence is excused, dissent is crushed, and cruelty is sanctified.

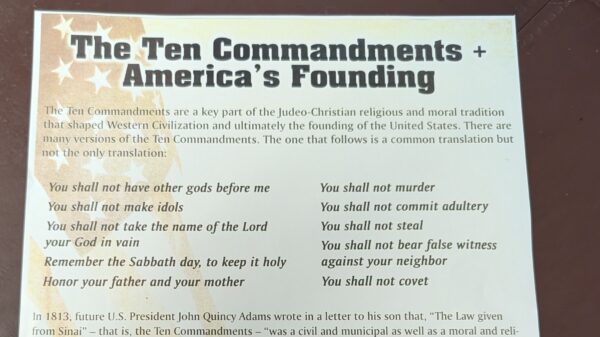

The First Amendment was written precisely to prevent that outcome. It does not merely protect religious belief; it restrains government from exploiting it. The prohibition against establishing religion and the guarantee of its free exercise work together to draw a firm boundary around conscience. The state may regulate conduct that harms others. It may not regulate belief, identity or faith itself.

That principle was not theoretical to the framers. They had seen the wreckage left behind by governments that claimed divine authority—sectarian wars, religious persecution, and tyranny enforced by certainty. The American experiment was designed to break that cycle by denying government the power to declare theology, define orthodoxy, or punish dissenting belief.

James Madison warned that the same authority capable of establishing one faith could just as easily exclude all others—and eventually turn inward. Thomas Jefferson went further, insisting that belief lies entirely beyond the reach of law. Together, they established a constitutional understanding that religious liberty is not granted by the state; it is protected from it.

American history shows what happens when that protection weakens.

Catholics were once branded as disloyal agents of a foreign power. Jewish Americans were excluded from neighborhoods, professions and institutions, regarded as threats to social order. Mormons were violently expelled from communities and denied legitimacy. Black Americans endured generations of domestic terror—often justified with religious language—used to enforce hierarchy, obedience and racial control.

Each episode followed the same pattern. Fear was elevated. Difference was redefined as danger. And exclusion was sold as protection.

Hatred in politics does not arrive fully formed. It spreads incrementally. It begins with language that marks an “other.” It sharpens into suspicion. It hardens into policy. Over time, citizens are taught—subtly at first, then explicitly—to accept cruelty as necessary and exclusion as virtue. That is how societies deform without realizing it.

Words matter because they prepare the ground. Terms like “infiltration” and “they don’t belong” are not abstractions. Historically, they have preceded surveillance, exclusion and violence. When such language comes from those who wield power—or seek to—it becomes permission rather than mere opinion.

There is also a cost Alabama must not ignore. We are told that Tuberville’s style of leadership will attract business and investment. But capital follows stability, openness and the rule of law. Talent follows belonging. In a global economy, rhetoric that targets religious minorities signals risk, not strength, and isolation rather than opportunity.

Alabama has lived this lesson before. We know the damage done when leaders trade constitutional restraint for grievance politics and call it courage. We are still working to overcome the legacy of those choices.

The Constitution does not promise comfort. It promises restraint—restraint on power, restraint on fear, restraint on the impulse to control belief. That promise survives only if it is defended when it becomes inconvenient.

History is unforgiving to those who mistake exclusion for strength and cruelty for courage—this is how the rot of hatred spreads, one soul to another.