During its fifth anniversary celebration, nonprofit Stand Up Mobile invited attendees to reflect on voting rights history’s impact on ballot access today.

The organization, founded in Mobile in 2021, is a nonpartisan advocacy aimed at improving voter empowerment, education and turnout.

Stand Up Mobile was originally conceived by founders Amelia Bacon and Beverly Cooper as a means of promoting communal and voter strength among Mobile’s Black voters following the events at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

“For many, including us, it was clear that for the sake of our democracy and its future, we could no longer remain on the sidelines,” Cooper said in a statement ahead of the event.

“We started with education and engagement to encourage voting as one of the key cornerstones of our democracy, our work has continued to expand as we saw needs. And, it has been nonstop,” she added.

The nonprofit’s anniversary reception, entitled “5th Anniversary Celebration: Revive the Village,” was held Friday night at the Pathway School: Mobile.

“Today, we celebrate five years of showing up, organizing, educating, and protecting our people,” Stand Up Mobile wrote on social media the day of the reception. “This anniversary is about impact. It is about the volunteers, partners, elders, young people, and neighbors who believed that Mobile deserves an engaged, informed, and empowered community.”

The celebration featured a keynote presentation from lawyer and civil rights activist Maya Wiley, who spoke on education and communal solidarity’s role in understanding the history of slavery, advancements of the Civil Rights Movement and empowering contemporary voters.

Wiley has served as the president and CEO of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights since 2022. She is a former candidate for mayor of New York City, university professor and chair of the New York City Complaint Review Board.

“Truth requires that we actually look, face and be honest about what is before us,” Wiley said. “Because we are not okay. We are not okay. Which is why ‘revive the village’ is such an important frame for what is a celebration—because we are not okay does not mean that we are not powerful.”

Wiley highlighted Mobile’s importance to Black history, pointing to the Clotilda, the last vessel to bring African slaves into the U.S., more than 50 years after importing slaves into the U.S. was outlawed, and Alabama’s importance in securing voting rights protections for Black Americans 100 years after the right to vote was ensured regardless of race.

“Today we are being told that even knowing, understanding and recognizing that very history and all that came after is in and of itself racism against people who are white,” Wiley said.

“When we talk about this flag, E Pluribus Unum, perfecting this union and what it means to have and be a democracy, we can’t do that without confronting what gets in our way,” she continued. “And what gets in our way is not knowing our history. It is not teaching our history. It is not debating our history. It is not understanding the meaning of the problems we have today in our community, and why we have them. It’s the people who want to take from us by keeping us ignorant.”

Wiley highlighted the facts that white landowners were the only individuals initially given the right to vote by the Constitution, and that Irish immigrants were widely considered white in America during the 19th century, arguing that understanding the divisive rhetoric of the past is essential to recognizing its presence today.

“Division means people go hungry. Division means people don’t get a good education. Division means people can’t organize labor unions. Division means that we have a debate about whether you can show up to the polls or not, even though you have a passport and have registered,” said Wiley.

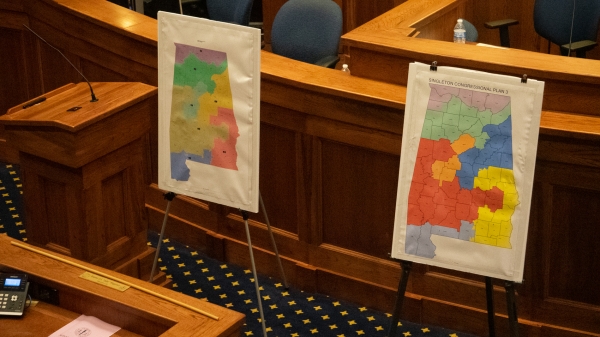

The speaker also pointed to the U.S. Supreme Court’s upcoming ruling in Louisiana v. Callais, and its potential impacts on the future of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. The second set of oral arguments for Callais, the facts of which mirror Alabama’s Supreme Court challenge to Section 5, Allen v. Milligan, were heard in November.

“Y’all won Milligan. We celebrated,” Wiley told the audience. “But now, it’s Louisiana’s turn, and we could lose that. We can lose what we gained in Milligan. We can lose what we gained in those 100 years fighting for voting rights.”

“That decision did not drop today, nor do we know what it will hold when it does. But I will tell you this—it don’t matter,” she continued. “Because whatever it says, we know we march on. Whatever it says, we will revive our village by making sure that every last one of our people knows where to vote, knows how to vote, can get a ride to the polls and when we have to, we will go to court and fight about it if someone gets in our way.”

Wiley ended her presentation by urging attendees to work to ensure they’re educated regarding threats to their voting rights and able to apply their frustration with politics to genuine pushes for change.

“Are you angry? Are you outraged? What does that do for us? Organize, mobilize, stand up, because it’s not until we’re fed up that we make sure we’re getting up for every last one of our people. That’s how it’s always been,” she said.