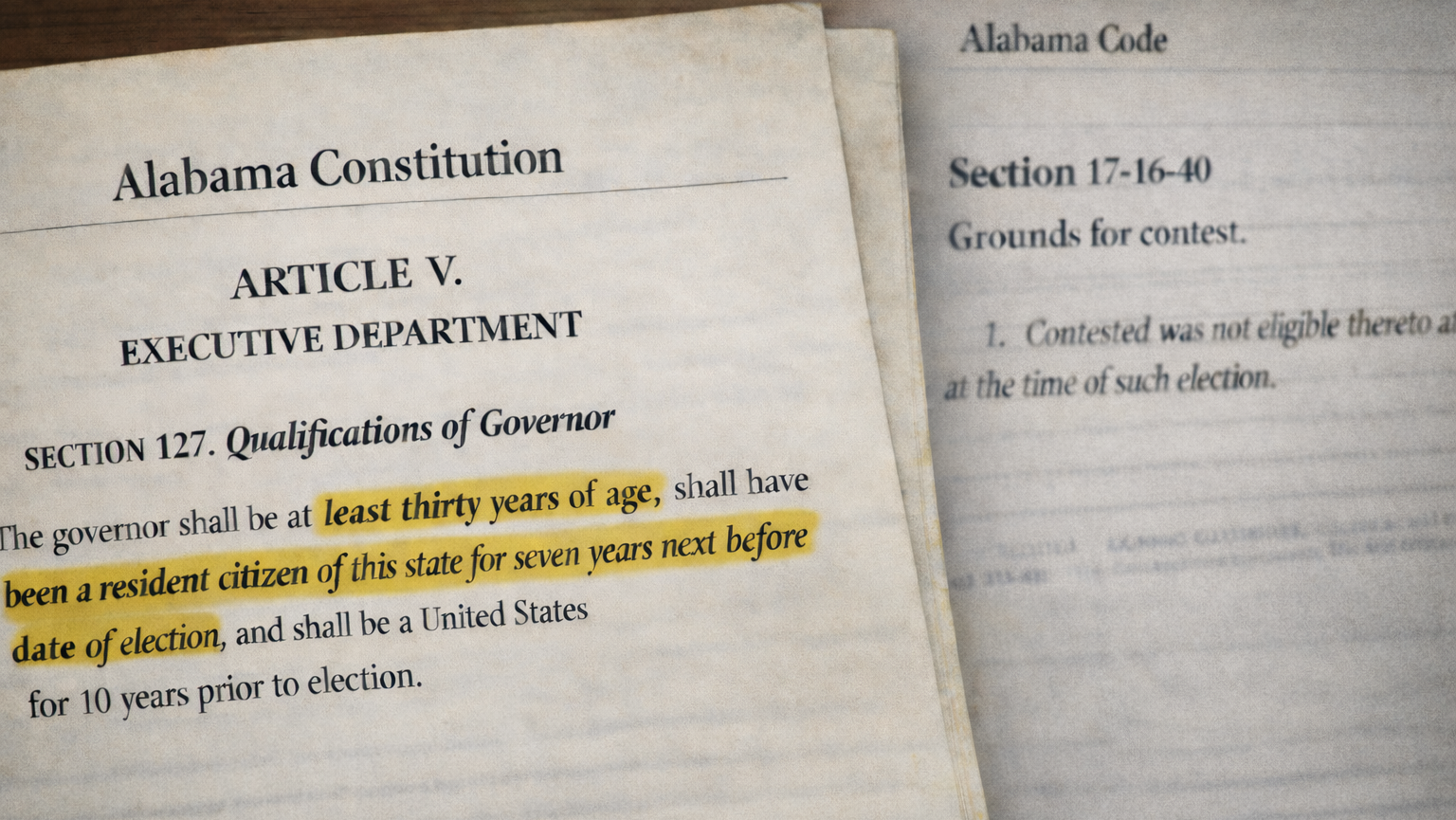

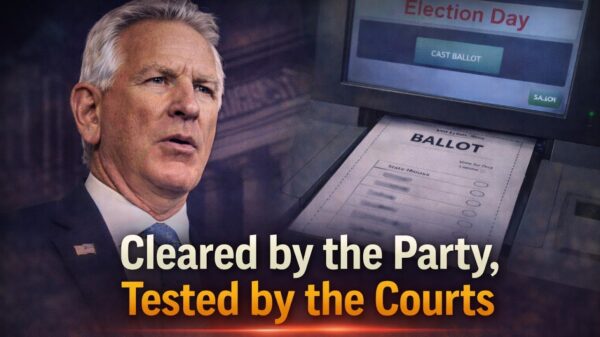

Since the Alabama Republican Candidate Committee cleared U.S. Senator Tommy Tuberville to run as a Republican candidate for governor, public discussion has largely turned on whether property ownership alone satisfies Article V, §117 of the Alabama Constitution, which requires that a governor be a “resident citizen of this state.”

The appeal of that argument is understandable. Property ownership feels concrete. It is easy to point to, easy to document and easy to explain. But Alabama law has never treated constitutional eligibility for public office as a question of real estate, convenience or lifestyle. It has treated it as a question of legal status.

Under settled Alabama law, a candidate may own multiple properties and maintain multiple residences, but may have only one domicile—and domicile, not property ownership, is the controlling legal inquiry under Article V, §117.

That principle is not open to interpretation or reinvention. Alabama courts have addressed it repeatedly, and with remarkable consistency. When residence is used in connection with political rights or eligibility for office, it is treated as a legal term of art. It means domicile.

The Alabama Supreme Court stated this plainly in Ex parte Weissinger, holding that “the word ‘resides’ … means legal residence and is equivalent to domicile.” The Court reinforced the same rule in Mitchell v. Kinney, explaining that “residence, when used in connection with political rights, means domicile.”

Those cases do not announce new doctrine. They reflect settled law.

Domicile, as Alabama courts define it, is a person’s true, fixed and permanent home—the place where the individual actually lives and intends to remain. Both elements must exist together. Physical presence alone is not enough. Intent alone is not enough. And once established, a domicile continues until it is affirmatively abandoned and replaced by a new one elsewhere.

This is where much of the public confusion arises.

Modern life makes it common for people to divide their time among multiple locations. Careers span states. Families relocate. Property is bought and sold. Alabama law recognizes all of that. But it draws a firm distinction between residences and domicile, and that distinction matters when constitutional eligibility is at issue.

A person may have several residences. A person may have only one domicile.

The Alabama Supreme Court stated the rule without qualification in Sachs v. Sachs, holding that “a person may have several residences, but only one domicile.” That rule controls here. No matter how many homes a candidate owns, the law recognizes only one place as the candidate’s permanent legal home.

Property ownership does not create domicile, and it does not preserve domicile once it has been abandoned. Alabama courts do not treat deeds, tax records or mailing addresses as dispositive. Those facts may be considered, but they are never controlling.

Instead, courts look to objective, real-world conduct. Where is daily life centered? Where are professional and personal obligations rooted? Do the individual’s actions demonstrate an intent to remain indefinitely? Intent is not inferred from statements alone. It is drawn from conduct over time.

This framework exists for a reason. Constitutional qualifications are not meant to be satisfied by paperwork or convenience. They are designed to operate predictably, without bending to political circumstance. That is why Alabama courts have consistently rejected efforts to blur the line between residence and domicile when political rights are at stake.

Article V, §117 applies to only two offices: governor and lieutenant governor. The framers did not require that a candidate merely own property in Alabama. They required that the candidate be a resident citizen of this state for a defined period. Under Alabama law, that phrase has a single, settled meaning.

It means domicile.

Political committees may make administrative determinations, and campaigns may offer explanations. But if eligibility is ever tested in court, the analysis will not begin with property records or travel schedules. It will begin—and end—with domicile, proven by conduct and intent.

That is not a partisan standard. It is not a novel theory. It is the law Alabama courts have applied for generations.

And it is the only standard that matters.