By Bill Britt

Alabama Political Reporter

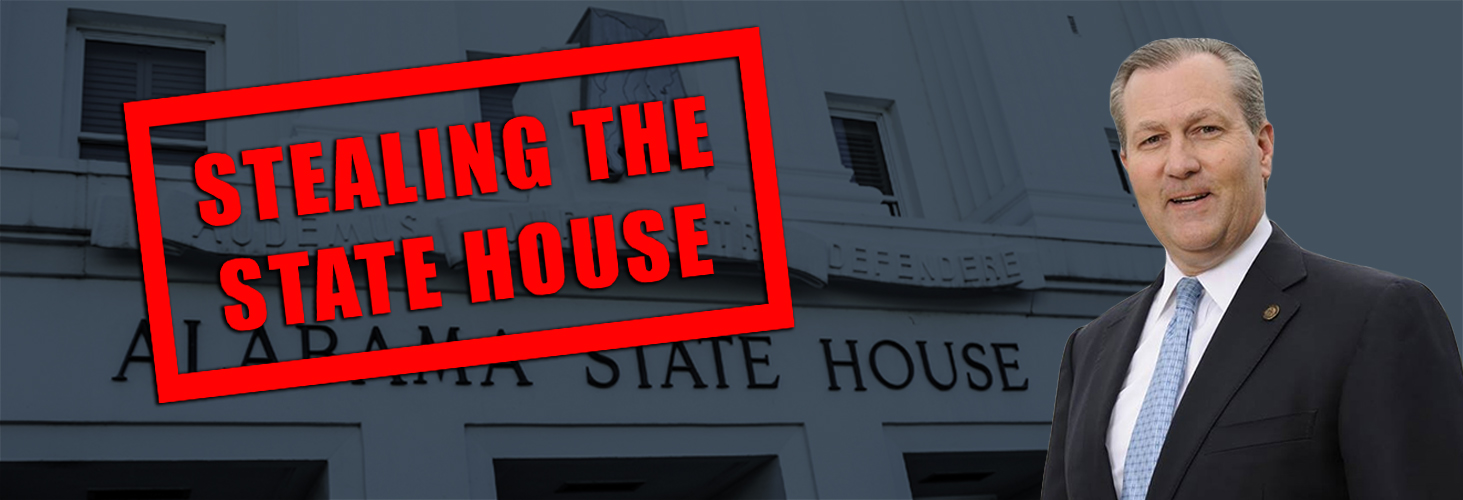

MONTGOMERY—The evidentiary hearing demanded by Speaker Mike Hubbard to expose prosecutorial misconduct and selective and vindictive prosecution concluded with only six of the 37 witnesses having given public testimony.

The six who gave testimony were, Henry T. “Sonny” Reagan, Howard “Gene” Sisson, James Sumner, Hugh Evans, Tom Albritton and Mark Colson.

The biggest takeaways from the three-day hearing were, Reagan has selective memory, Sumner has a scholarly grasp of the State’s Ethics laws, Albritton isn’t anyone’s lapdog, and Colson had a surprise.

Reagan, who took the stand for around three hours, gave a stellar, if dishonest, performance under direct examination by Hubbard’s attorney, J. Mark White. Reagan offered no new evidence but as if by rote, recited the various threats he claims Deputy Attorney General Matt Hart made against Hubbard. White would have the court believe that these alleged threats rise to the level of prosecutorial misconduct.

During direct, Reagan had total recall of every conversation with Hart, but under a withering cross examination, Reagan could not recall a series of conversations with Hubbard’s former chief of staff, Josh Blades. When questioned by Solicitor General Andrew Brasher, Reagan could not remember several conversations with Blades where he revealed Grand Jury information he gathered at the Attorney General’s Office, and could not recall discussing employment as the Speaker’s legal counsel. Brasher made it clear he believed Blades had a different recollection of events. This has left the impression that Blades has fully cooperated with the prosecution as this publication speculated more than a year ago.

The facial expression of the Judge’s staff showed telltale signs of unbelief as Reagan repeatedly claimed he could not remember specific events or statements, not even when and why he hired Rob Riley to represent him, even though it was clear that Riley became his counsel before he filed the personnel complaint against Hart and before being called to testify to the Grand Jury.

The second witness for the defense was former Attorney General Special Investigator Sisson. He was on the stand for less than ten minutes because the testimony the defense wanted presented was inadmissible. Hubbard’s attorney, Lance Bell, tried to introduce testimony about an ethics complaint filed by Sisson. The complaint, based solely on hearsay, was ruled inadmissible by Judge Walker. A visibly angry Sisson stormed from the courtroom in a rush. Hubbard and White had repeatedly stated the first three witnesses would prove devastating to the prosecution leading to dismissal of many of the charges.

Third up was former Ethics Director James Sumner. He was called to testify to the constitutionality of some of the State ethics laws, primarily the section on a Party Chairman being placed under the code dealing with public officials:

“A public official includes the chairs and vice-chairs or the equivalent offices of each state political party as defined in Section 17-13-40.”

Hubbard is charged with using his office as Chairman of the Republican Party to enrich himself.

Sumner did not back down from his assertion that the code followed “Black Letter Law,” and had never been challenged in the two decades since it codification into law in 1995.

On this and other issues Sumner adroitly countered White’s attempt to paint State ethics laws as vague and confusing.

On cross examination, Summer carefully explained the difference in formal and informal ethics opinions. Sumner said, formal opinions are official ethics opinions voted on by the ethics commission. Alabama law affords a great deal of weight to formal opinions, going as far as providing a great deal of protection from prosecution for those whose conduct remains within the confines of behavior outlined in a formal ethics opinion.

Informal opinions, according to Sumner, are distinguished from formal opinions in that the commission itself does not approve of the advice, and it affords no protection from prosecution for those seeking informal opinions. Sumner said he has provided informal opinions in forms ranging from letters to phone calls to conversations while standing in line at Starbucks.

As this publican reported in 2013, Hubbard in January 2012, signed a contract with Southeast Alabama Gas District (SEAGD) which paid him $12,000.00 a month for economic development.

In an informal opinion, the ethics commission’s legal counsel Hugh Evans wrote, “The general prohibition continues to apply, in that the Speaker may not use his position or mantle of his office to assist him in obtaining consulting opportunities or providing benefits to his consulting business or his clients. Otherwise other than this we see no problems.”

But the indictment shows that Hubbard did use the mantle of his office as Speaker in lobbying Gov. Robert Bentley, and other members of the Executive Branch on behalf of his client without their knowledge.

Sumner sternly took exception to White’s misquoting and pulling his statements out of context. Sumner was a formidable witness, just not for the defense as they had hoped.

No startling new information came from the first three witnesses as Hubbard and his team had promised. With the exception of a partial revelation that Blades had obviously spilled his guts to the prosecution, little of note came from the first three witnesses that wasn’t already known.

The fourth witness was Hugh Evans, chief legal counsel for the Ethics Commission. Evans testified the commission had searched and produced all records requested by the defense.

Current Director to the Ethics Commission Tom Albritton was the fourth witness and echoed much of what Sumner had stated earlier. Augusta Dowd was tasked with taking Albritton’s testimony. The pair had a tense exchange when Dowd questioned why Albritton had not returned her calls.

Albritton countered by saying, Dowd had texted him, but did not call him, as agreed upon. Dowd seemed unprepared for the push back. Albritton went further reminding the defense that he had a job to do for the people of Alabama, and could not be at White’s beck and call.

The last witness to testify in open court was Mark Colson, Senior Vice President for Governmental Affairs and Chief of Staff for the Business Council of Alabama (BCA), led by Billy Canary, who is named in the Hubbard indictment.

Colson’s testimony was designed to show a selective and vindictive prosecution.

He was asked, in a series of questions, if he knew Jessica Medeiros Garrison, Melissa Strange and Luther Strange. Colson acknowledged that he did. The defense then produced an email in which Garrison had asked if he could meet with Mrs. Strange about a company she represents which processes credit card payments. Colton acknowledged that he had received the email, and had indeed met with Mrs. Strange. The defense then asked the money question. Did BCA change credit card processing providers after the meeting with Mrs. Starnge? Colton leaned into the microphone and said, “No.”

Court observers and several seasoned defense attorneys noted, that only amateurs ask such questions without knowing the answer ahead of time. There were no Perry Mason moments like the defense was hoping for. At best, they were unprepared, and at their worst, incompetent.

On day three, the hearings continued behind closed doors, and is yet a secret to the public.

Several legislators were scheduled to testify about events which took place during Grand Jury testimony, among them was Rep. Ed Henry, who states he was never called to the evidentiary hearing.

White informed the press that “He couldn’t have been more pleased,” with the hearings. Chances are he is lying to himself or the public.

The consensus among the several defense attorneys who observed the hearing is that Hubbard had a bad few days that will not lead to any dismissal. Most agreed the only good turn for Hubbard was the biased media coverage especially coming from his home town paper the Opelika-Auburn News, where the reporting might taint the jury pool.