Early last week it said 7,500 would die in Alabama by August.

This modeling from the University of Washington’s Institue for Health Metrics and Evaluation has been cited by the White House’s coronavirus task force.

This modeling — that last week suggested somewhere between 100,000 and 240,000 Americans could die — spurred President Donald Trump’s decision to extend social-distancing guidelines through April and served, at least in part, as a call to action for Alabama to issue its stay-at-home order Friday.

Then it was revised downward again to 5,500. As recently as this weekend, the model projected that Alabama would have the highest per capita death rate in the country and the fourth-highest total death toll.

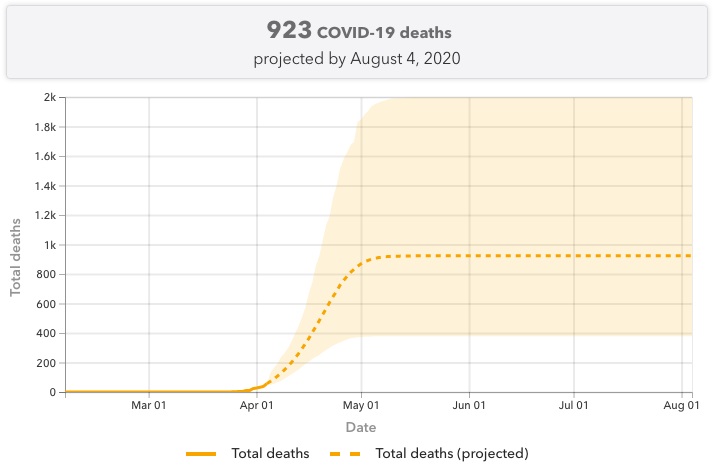

But by Monday morning, it was adjusted again — this time projecting fewer than 1,000 will die by August from the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Instead of the highest per capita death rate in the country, Alabama is now projected to fall somewhere in the middle — 22 out of 51.

The changing numbers and the shifting projections can tell us many things but one is this: that modeling a pandemic is hard, especially when how it pans out depends heavily upon how state governments and the people adhere to social-distancing guidelines. No one knows how this will end.

I spoke with Dr. Ali Mokdad, one of the senior scientists at IHME and a former official at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He helped develop the model. (We spoke before the model was revised downward for Alabama.)

IHME’s model is live. It is updated regularly. It was never meant to be interpreted as a comprehensive prediction of the future. It was intended as a planning tool to help policymakers, hospital officials and the public plan ahead. In fact, the people who made the model hope their projections at present are wrong — that they will be revised downward more.

“By reducing the number of people who have infections by staying at home, you can help the medical system,” Mokdad told me. “And when the peak comes, that shortage that we are projecting will not be as big as we are seeing right now because social-distancing is working.”

The updated modeling shows how social-distancing is working, not that it was never possible that 5,000 or 7,000 people could have died. Had we not acted, had people not changed their behavior, had the state not implemented a stay-at-home order, that could have surely been the case — and it still could be.

State Health Officer Dr. Scott Harris said the model has been helpful in planning for the peak.

“I think the thing that’s been most helpful about that model is really the timelines,” Harris said in an interview with APR.

“The margin of error they have on there is tremendous,” Harris said. “I don’t necessarily think it’s incorrect, but you can almost read what you want to on there. We could have 50,000 deaths or 5,000 deaths or any number. But the timeline makes sense, seeing when we’re expected to have a surge. That was what was most useful to us.”

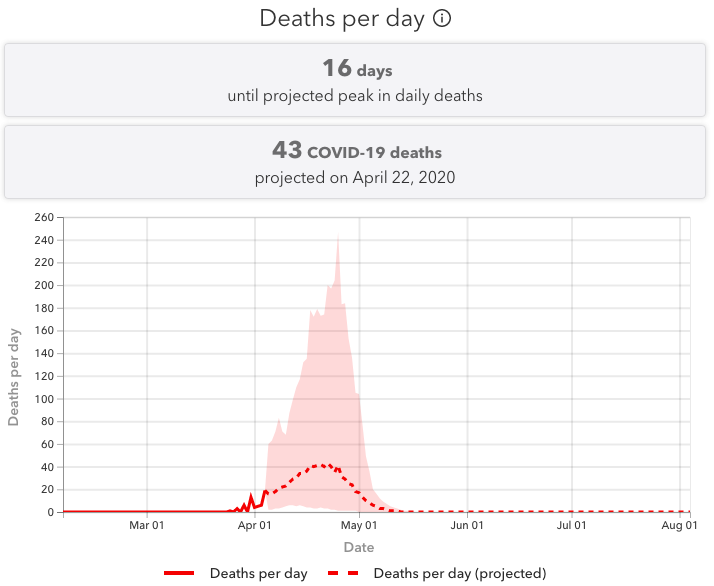

The shaded area indicates uncertainty in the modeling, ranging from 1 to 247 deaths per day on April 25.

A model is only as good as its inputs. Last week, IHME’s model for Alabama had little data to work off of. The state had only just begun to report deaths. And when the state changed its reporting of deaths, and the death toll spiked as a result, IHME’s model — which is primarily based on deaths per day — adjusted.

“So one day they just kind of flipped the switch, and suddenly our numbers changed dramatically in one day even though the situation on the ground was the same,” Harris said. “I am not saying they are wrong, but the timeline is most useful.”

Even though the number of deaths per day is still increasing, the state hasn’t seen a similar jump since last week. The model, as a result, has stabilized, too.

The shaded area indicates uncertainty in the modeling, ranging from 400 to 2,000 total deaths by August.

As more data becomes available, the model will adjust again. The projections could worsen if deaths begin to spike, or the projections could get better if deaths level off before the projected peak in mid-April.

“People are working tirelessly not only to make sure that we’re going to be able to handle the need for ventilators in the coming weeks but also that we have the surge capacity to figure out if we do exceed the number of beds that we have, how we can deal with that,” Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo, the director of the infectious diseases division at UAB, said last week. Marrazzo is also a member of Gov. Kay Ivey’s coronavirus task force.

There are a number of assumptions in the model, including complete adherence to social-distancing measures through August. If Alabamians flout the stay-at-home order that began Saturday evening, the projections could surely be wrong — the reality could be worse. The death toll could be much higher than nine hundred because Alabama remains particularly susceptible to the virus.

“When you look at Alabama, there are more people who have risk factors in Alabama and the Southeast in general,” Mokdad said. “More obesity, more high blood pressure, more diabetes and more cardiovascular disease, and more cancer there than really anywhere else.”

If we try to return to normal earlier, then the projections could be worthless because the model assumes social-distancing continues through August. If we stop social distancing, about 97 percent of the population would still be susceptible to the disease. The virus would surge again. Until a vaccine becomes available, the virus and the threat of mass casualties could return.

“Our bodies as a species, we have never seen this virus,” Marrazzo said. “And that’s why so many people are having such a hard time handling it after getting infected.”

That threat could be mitigated by a nationwide mass testing regime, which would enable widespread contact tracing and targeted quarantines. That testing regime would have to include the large number of people who show no symptoms. We are nowhere near the capability of testing the number of people we would need for that to work.

The revision of the death toll from 5,500 down to 900 should not be taken as an all-clear. The modeling is based on the actual death toll, which could change if our behavior changes.

Below is a Q&A of our conversation. It was edited for length and clarity.

Q: Why does the modeling look so bad for Alabama?

Dr. Mokdad: It doesn’t look good, but let me explain why. We are modeling mortality. We take the death rate and model off that. We project the death rate into the future.

Then we back-calculate the number of beds, ICU beds and ventilators that are needed. Because we know from hospitals right now how many people with COVID-19 showed up at the hospital, how many were on a ventilator, how many of them needed to be in an ICU bed, how many died and how many survived. So we can do that by calculation.

The reason we are modeling mortality and not how many cases we have is because we are concerned that we are not testing everybody who needs to be tested. So the number of confirmed cases that we are releasing as a country is not totally reflective of reality. And this is not a criticism of the country; it’s just the reality. But we are reporting as positive the people who came and got tested. And we have still a shortage of tests.

Second, there are people out there who may have COVID-19 but are asymptomatic. We have studies showing that they don’t have any symptoms. We know people who were tested here in our hospital, who were positive, but they never had any symptoms. They were tested and they were found out to be positive. But they can still pass the virus, even though they don’t have any symptoms. We also know that many have mild symptoms and may not require hospitalization. Or some who have symptoms but may think it’s something else, like allergies, especially in a state like Alabama, which is beginning its allergy season.

So we decided to model mortality. We project a peak of demand — demand of the medical system — in mid-April.

The reason why Alabama would be much worse than most other places is a number of factors. When you look at Alabama, there are more people who have risk factors in Alabama and the Southeast in general. More obesity, more high blood pressure, more diabetes and more cardiovascular disease, and more cancer there than anywhere else.

So we would expect people who are high risk to use more resources because they have conditions that would make mortality higher and there will be more demand for resources.

Q: Gov. Kay Ivey just issued a stay-at-home order. A lot of people have said that came too late. How does that play into this model?

Dr. Mokdad: So in our model, we monitor all of these decisions. We know that you closed schools. We know that you closed non-essential businesses and services should be closed. But at this time, we have not added the stay-at-home order. That happened today.

It’s really too late, unfortunately. From our perspective, it should have been done much earlier. We cannot change the past, but we can change the future. So the lesson here is that these orders should have been in place earlier, but from now on, what we really need to stress for people in Alabama, is by staying home and adhering to these social distancing guidelines, you can reduce the number of deaths. The most important part for Alabama is that it could have a shortage of facilities to take care of patients.

By staying at home, you can reduce the burden on the hospital system. You can allow your physicians to have at hand the resources they need to deliver the best medical care for everybody who needs it. By reducing the number of people who have infections by staying at home, you can help the medical system and when April 17 comes, that shortage that we are projecting will not be as big as we are seeing right now because social distancing is working.

Q: Can you talk about the timeline and why this might have come too late for the peak demand?

Dr. Mokdad: I’m not saying it’s too late to do anything. The decision was made too late. It should have been done much earlier. I’m not picking on Alabama. Even in Washington, I would have liked my governor to make that call much earlier.

I and everybody in this country, we saw a pandemic unfolding in China. We saw how aggressive their measures were. We know they suffered. We saw it. So why didn’t we prepare ahead of time for it? We knew this was coming in December or January. We had January and February.

We had over a month and a half to prepare. Let’s be realistic and say a month because the first case was in Seattle. So let’s say we had a month. Why are we having this discussion now about our capacity to produce ventilators? We are the United States of America. We have the best resources. We have the best minds here. We are a resilient population. If you inform the public and give them the right information at the right time, Americans love their country and want to protect each other. So they would have stayed at home. All of us should have made this call much earlier. It’s too bad that Alabama did it on April 4th, when other states started doing it in mid-March. Even those states should have done it earlier.

Q: What should people take away from your modeling?

Dr. Mokdad: We can still make a difference here by staying at home. We have to be very careful. At this time, especially in a state like Alabama, where I worked a lot with the CDC. I worked a lot in Alabama. We know the state has underserved populations. It has many minorities and vulnerable populations. We need to be compassionate.

It’s time for all of us right now, all of us in other states, to help Alabama. Alabama should not be left alone to deal with this burden. It’s time for us to focus on Alabama. I know New York is in the media, and they deserve that, but we should still not forget Alabama. You should not be left alone to deal with this.