The Alabama House Judiciary Committee on Tuesday sent a bill who’s sponsor says would strengthen criminal penalties for rioting, but that others worry would criminalize peaceful protesting, to a subcommittee for further work.

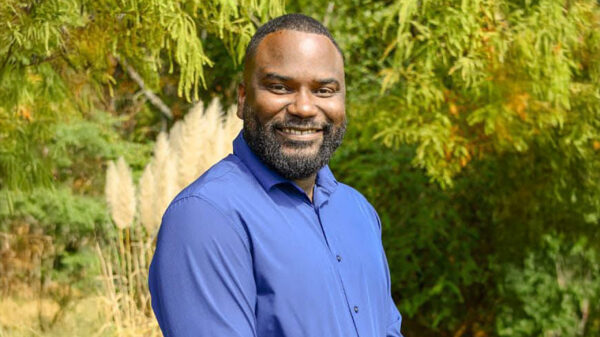

Rep. Jim Hill, chairman of the Judiciary Committee, sent the bill to a subcommittee at the conclusion of a public hearing on the bill, and at the request of the bill’s co-signer and of Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa, who voiced concern that the bill could have dramatic “unintended consequences” that could result in the felony arrests of peaceful protestors.

Rep. Allen Treadaway, R-Morris, former assistant police chief of the Birmingham Police Department, said his House Bill 445 does not aim to stifle free speech, but rather to prevent violence seen at protests in Birmingham and elsewhere over the summer.

The bill would also penalize cities by withholding state funds if a city “abolished or disbanded, or substantially abolished or disbanded” a law enforcement agency without plans to immediately restart the agency, or if the city were to cut the agency’s funding by 10 percent or more without redirecting a majority of the money to other policing programs.

Treadaway’s bill would also require anyone arrested for participating in a riot, blocking traffic during a protest or assaulting a first responder to remain in jail for 48 hours before becoming eligible for bail.

“What took place was very disturbing in the city,” Treadaway said, adding that the night before the protest “individuals came to Birmingham and planted incinerate devices, sledgehammers, brick in the shrubbery around our businesses downtown.” Treadaway said that came to light by looking at security footage after the incident, and that was done during the process of investigating some who’d been arrested that night.

It was unclear Tuesday whether such activity has been mentioned by Birmingham police prior to Tuesday’s public hearing. A search of news accounts covering the protest didn’t reveal mention of any such security footage of people placing those items in bushes, and attempts to reach Treadaway on Tuesday were unsuccessful.

The protest began peacefully on May 31, 2020, at Birmingham’s Kelley Ingram Park, where a Confederate monument was at the center of a court battle and between city officials, who wanted it removed, and Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall. Protestors that night tried to pull the monument down but were eventually moved by police out of the park, and some in the crowd damaged buildings as they left.

Birmingham Police Chief Patric Smith said at the time that 14 businesses reported burglaries and 13 had extensive damage.

“Approximately 70 people were arrested, or more, but about two-thirds of them were from out of town,” Treadaway said during the public hearing.

More than 70 people were arrested on charges ranging from curfew violations, failure to disperse and disorderly conduct, according to Birmingham City Attorney Nicole King at the time, reported by AL.com. King said that 27 of those arrested or 38 percent, were from Birmingham, and charges against them would be dropped. Those facing property crime charges would be prosecuted, however, she said.

Birmingham police later arrested another 10 people on charges related to burglary and property crimes. Of those arrested, seven are from Birmingham, one from Talladega, one from Guntersville and the last person could not be located in court records, according to APR‘s search of those records.

Protests in Birmingham, Huntsville and across the country followed the death of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis. The Black Lives Matter campaign came to prominence over the summer, with people of all colors coming together and urging for police reform and an end to the killing of unarmed people of color by police.

Of the four visitors to Tuesday’s public hearing who spoke out against the bill was David Gespass of the National Lawyers Guild, which trains attorneys to act as observers during protests.

“Our experience has made it clear that the primary threat everywhere is not to law enforcement personnel, but to the First Amendment,” Gespass said. “Thousands of dismissals and not guilty verdicts have been won by guild lawyers around the country. Tens of millions of dollars have been recovered in civil actions for violations by police of protesters’ rights. This is the reality we see daily, and yet this bill seeks to strengthen the hands of the police and further punish protesters.”

Dr. Howard Robinson, archivist and associate professor of history at Alabama State University, said that as a historian the bill looks familiar to him.

“In that it is part of a long Alabama tradition, intended to intimidate, crush and incarcerate citizens, minority citizens, who like minority citizens the world over seek redress of government through protest,” Robinson said.

Rep. Mary Moore, D-Birmingham, said the bill took her back to the days of Bull Conner and described the former Birmingham commissioner of public safety driving away civil rights protestors from city parks, including herself.

“I can promise you every day Bull Connor chased me. He would get in that white tank and chase us out of the park,” she said.

England focused on the bill’s definition of a protest, expressing concern that the broadened definition would place the burden on defining what is and isn’t a riot on a police officer and could result in the arrest of peaceful protestors.

The bill defines a riot as: “A tumultuous disturbance in a public place or penal institution by five or more persons assembled together and acting with a common intent which creates a grave danger of substantial damage to public, private, or other property or serious bodily injury to one or more persons, or substantially obstructs a law enforcement or other government function.”

“One thing that you’re missing from this definition is an act. So essentially an officer could find what a protester said to be objectionable and arrest that person for it,” England said. “But not just any normal arrest, because what happens from that point forward is there’s a mandatory hold.”

England said under the bill an officer would have to determine whether a protest was in fact a “tumultuous disturbance” versus a “regular disturbance,” as well as whether a person is “substantially” obstructing or just obstructing.

“All these decisions have to be made by somebody in a split second, on the street, in the middle of a protest, so in itself, this language is unenforceable on the street and is certainly un-prosecutable in a courtroom,” England said.

Treadaway responded that the definition in the bill including the definition of a riot has been on the books for years.

“The intent of this bill is a conviction on some serious crimes. This is to protect the public. Protect free speech. Protect protesters. That’s what this bill does,” Treadaway said.

England later spoke again during the hearing and said the bill’s definition of riot is in fact a new definition.

“There’s no question about it. This is a brand new definition. It’s specifically constructed for this bill because it is giving law enforcement the ability to engage in content-based restrictions,” England said.

England said the bill’s proposed 48-hour mandatory hold is longer than a hold a person who’s arrested for spousal abuse would receive.

“The reason why I can’t stand the fact that people rioted and busted out windows and all these sorts of things is because it gives people the ability to ignore why we were there in the first place,” England said.

Rep. Merika Coleman, D-Pleasant Grove, said she’s concerned that her own children, who have become politically active, could be arrested for taking part in a peaceful protest if the bill becomes law. Under the bill, if someone in the crowd were to throw a brick, everyone in that crowd could be arrested and charged with crimes related to rioting, those who spoke out against the bill noted.

“This impacts my children. This is not a piece of public policy that I will never see how it impacts folks,” Coleman said.

“My kids are college students. You talk about possible felony convictions for the things that they want to achieve in life? You put a record or a spot on them for the rest of their lives. Unintended consequences,” Coleman said.

Rep. David Faulkner, R-Mountain Brook, spoke in support of the bill, and said he hadn’t studied the bill as closely as he should have, and that he’d do so after the hearing, but that he “didn’t see an attack on peaceful protestors” in the legislation.

“I have always felt that your intention of this was to protect peaceful protest,” Faulkner said.

England, responding later to Faulkner’s statement, said “but you pass it to humans.”

“When you pass a law to humans, you pass it to their biases,” England said. “You pass them to their prejudices.”

England said there are cases across the Supreme Court history that throw such laws out because “they’re unconstitutionally vague” and could result in the arrest of people for lawfully expressing their First Amendment rights to free speech.

“Alabama will become one of the few places in the world where the truth can get you arrested,” England said.

Treadaway stressed that his bill doesn’t intend to clamp down on free speech and that outsiders have begun arriving at protests to “hijack the situation and create chaos for their agenda, that I’m not going to get into.”

“I’ve got my own personal … but I’m dealing with facts,” Treadway said, seeming to refer to his personal beliefs about the agendas of those outsiders he spoke of. “So that’s what’s occurring. This bill, to me, is going to keep all life safe.”

Rep. Allen Farley, R-McCalla, a former Jefferson County assistant sheriff and co-sponsor of the bill, said he supports the legislation, but also supports England’s request to place the bill in a subcommittee for further work

“I look forward to your bill becoming law,” Farley said. “But I think we need to slow it down a little bit. Let’s bring the backgrounds and the paths of these individuals around a table at a subcommittee. Close the door. Let’s talk about things that we sometimes don’t talk about, and make this bill stronger.”

Hill placed the bill in a criminal subcommittee to be brought back up to the House Judiciary Committee on March 17.

Hill also said he was attaching Coleman to the subcommittee so that she could partake in those discussions.