A new grassroots organizing coalition aims to demystify the redistricting process for voters across the state. While its leaders don’t expect to affect how congressional and state legislative districts are drawn, they anticipate changes at the layers of local government beneath them.

Felicia Scalzetti, a former census worker, is one of four fellows hired by the network. She covers central Alabama and the Wiregrass region. She will study the census data when it is released so her team can begin constructing their own maps to present at redistricting hearings.

“We’re all waiting kind of on pins and needles for the rough data to come out in mid-August, and then the official cleaned-up data will be out by Sept. 30,” Scalzetti said.

The Alabama Election Protection Network was formed last year and is partnering with three existing outreach organizations. Two are Black-led: the Ordinary People Society, a faith-based national nonprofit and AEPN’s lead founding organization, and Alabama Black Women’s Roundtable, headed by Jefferson County Commissioner Sheila Tyson. The third is the Hometown Organizing Project, founded by Montevallo resident Justin Vest.

Vest has been doing a series of one-on-one virtual trainings to teach volunteers how to spread the word about redistricting. He founded his group two years ago in response to the tornado that killed 23 people in Lee County in March 2019. Its focus is building sustainable and inclusive rural communities across Alabama, and the majority of the work has been disaster response and preparedness. In the first months of the pandemic, they formed a 1,000-strong statewide network of volunteers who made masks for frontline workers facing shortages of Personal Protective Equipment.

An important part of disaster preparedness and response is having local government that is responsive to the needs of its constituents, Vest said.

He grew up in small-town Alabama and currently lives in a community of fewer than 7,000. The workings of government are less visible in rural communities that don’t have local reporters keeping tabs on public officials, making it easier for them to do what they want without anyone holding them accountable, he said.

That leads to the low-income, working-class residents of those areas giving up on government.

They are Vest’s target audience. Part of educating them about how redistricting can change their realities is acknowledging that their cynicism is justified.

“Like, you’re absolutely right — the government is not working for you and it is by design,” he said.

Their participation is crucial to changing a status quo that is often defended by people in positions of power. In Alabama, many of them are Republican, but AEPN’s Our Districts, Our Alabama initiative recognizes that gerrymandering is a tool for consolidating power used by anyone in control.

“Quite frankly, it doesn’t matter what political party they’re a part of,” Vest said. “Their interest is maintaining their own elected positions, and so they want to keep their districts. Essentially, they want people in their districts who will not ask questions, not demand a lot of them.”

The campaign is advocating for changes both short-term and long-term. Education is a main component. If voters learn how redistricting works and what the rules are, it creates a level of accountability for the office-holders drawing the maps.

Vest starts with people who are already actively trying to improve their communities. The best organizers he trains are people who’ve been doing a lot behind the scenes without much attention, he said; people who others know to contact when help is needed because they’ll help if they can or connect them with someone who can. Helpful neighbors act as informal mutual aid networks that can be drawn on for civic engagement outreach, especially because they know the local issues intimately.

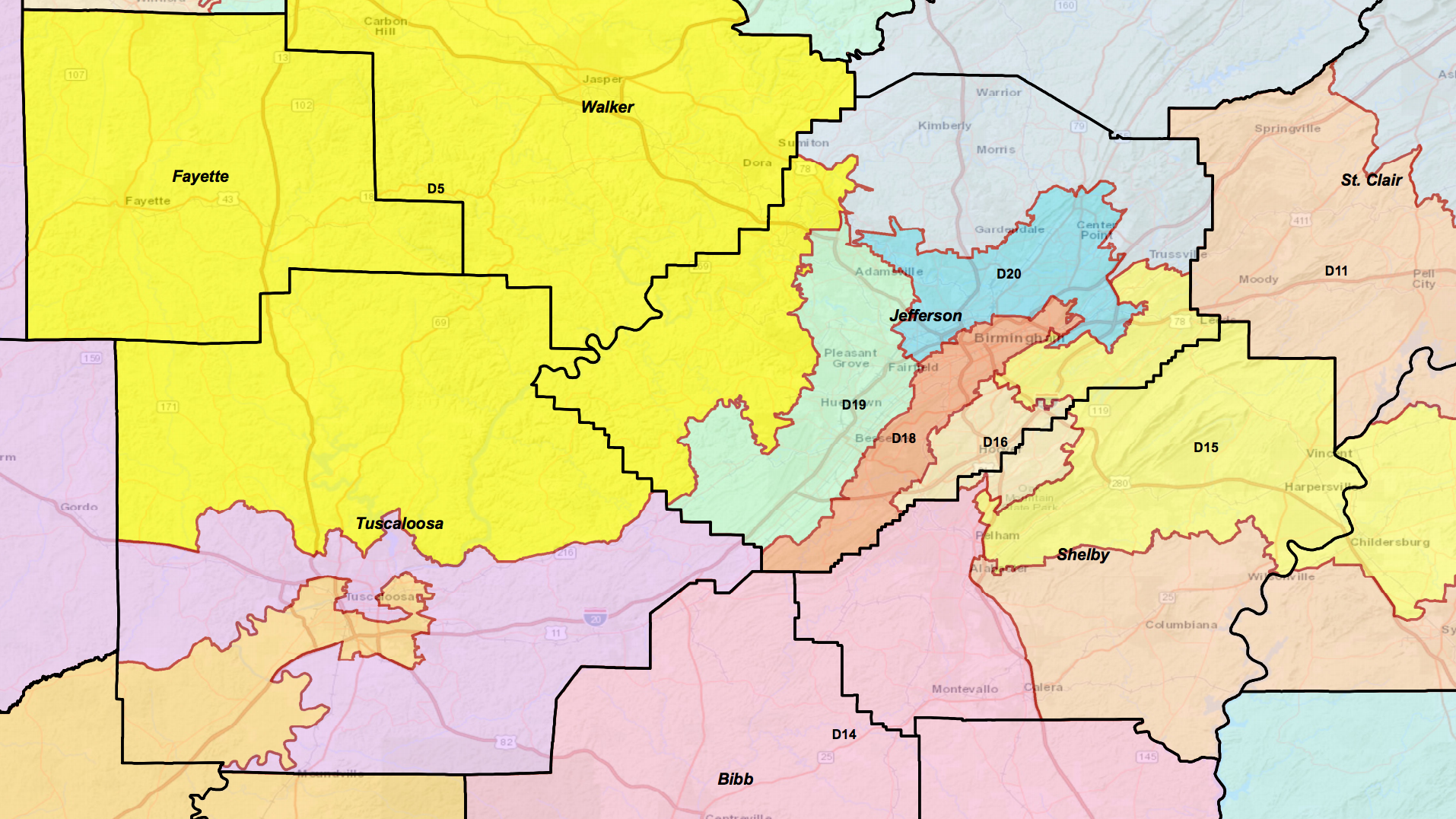

State legislators don’t do much to publicize the process or make it accessible to the general public, Vest said. But local residents know what their communities’ shared interests are and where neighborhoods begin and end, which matters for things like city council districts. While gerrymandering has gotten more attention in recent years, people forget about local districts, Vest said. County commissioners have to draw their maps just like state legislators do.

“I think that’s where we’ll really see change,” he said.

Scalzetti said she’s eagerly awaiting what the data will reveal about changes in population. The easiest way for an incumbent to stay in office is for them to keep their map the same, but because districts are required to have the same approximate number of people, population changes mean borders will have to change.

Due to significant growth in Alabama’s population in the last two years, Scalzetti said, some officials will have to go to the drawing board.

Her outreach strategy is informed by her census work. She learned to communicate with people who were distrustful of government surveys by listening to their concerns and working around them, like keeping their responses anonymous but making sure they were counted.

For her, it’s about explaining why people should care. Local maps determine where kids go to school, if an area gets its own water district or whether a representative is splitting your community in half, which would require their office to coordinate with a second office for disaster response and other important actions.

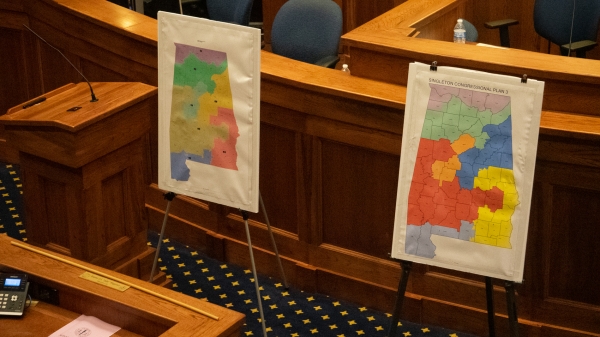

She’ll be teaching people how to use Dave’s Redistricting, a free online tool that anyone can use to draw their own district maps to better understand the process or that they can bring to the upcoming hearings “and show legislators exactly what you’re talking about and why it’s possible,” she said.

Scalzetti is worried that hearings are being planned for early September before the official data is released. It still hasn’t been announced whether they will allow public comment. They’re expected to be held during working hours on weekdays when few people can show up. If she submits maps, they’ll be based on the rough data that was released, which enables officials to dismiss them because the official data won’t be released yet.

“That is just a fundamentally messed up situation. You’re not actually trying to do anything fairly, you just want to get this over with,” she said.

As more people get informed, however, more can get involved. Scalzetti and her colleagues want to build a critical mass of residents who know what redistricting is and who can provide accurate information about their communities that can be compared to the maps that officials propose.

“And I can look at this and go no, no, no — this is what they’re doing, and we can change it,” she said.

A long-term goal of hers is to push for an independent or citizen redistricting commission that would be elected. Nine states have independent commissions. Thirty allow the party in control of the state legislature to control the process. Alabama is one of 21 states where the process is controlled by Republicans. Nine are Democrat-controlled and 11 states split control between the two parties.

A citizen board that is elected would be the best way to make sure that maps that are submitted will be looked at, Scalzetti said.

Vest said he’ll continue his trainings, using the network he has developed throughout the state to multiply the coalition’s message.

“It’s really a tremendous opportunity for small town residents to come together around their shared interest and demand better from their elected officials, if you’re not happy with the way things are going,” he said.