House Bill 312, sponsored by Rep. Ed Oliver, R-Dadeville, doesn’t expressly mention Critical Race Theory anywhere in its text.

But it is one of the bills many have been waiting on in the state’s battle against CRT despite the theory not being taught at the K-12 level according to State Superintendent Eric Mackey.

The critics showed up Wednesday for a public hearing on the bill during the House committee on state government, with 11 people coming forward to oppose the bill.

Oliver told the committee that the bill is not just to ban CRT, but to “fight for a colorblind America” by “banning some racist concepts.”

The bill does not ban the teaching of the divisive concepts, but prohibits teachers from forcing students to “adopt or believe” such concepts.

Committee chairman Chris Pringle, R-Mobile, limited committee members’ debate on the bill, stating that there would be no vote on the bill a this committee meeting, and instead spent the time to listen to the public input.

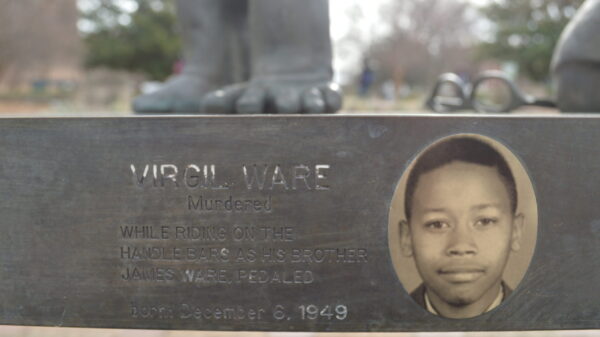

Steve Murray, director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, opposed the bill overall, but asked specifically for the removal of section K of the bill, which states that slavery should be taught only as a betrayal or failure of American values including liberty and equality.

“The evidence tells us that the American experiment is a two sided coin, featuring on one side the promise of liberty and equality while engraved on the other side with chattel slavery, broken promises to indigenous peoples and codified discrimination. The existence of the reverse side of the coin should not displace the founding principles and our image of America. It’s important to be clear about that, but it must be examined alongside those principles as a core part of the American experience and not merely a regrettable deviation from an otherwise ideal progression of the nation’s development. This is difficult work. But the outcome is a healthy patriotism that acknowledges the faults in our history while remaining committed to the process of building a more perfect union.”

He also challenged the committee that the other divisive concepts listed in the bill are not an issue found in Alabama schools.

“During my 16 years at our agency, our staff has never encountered an Alabama educator who seeks to use history or civics to set one group of students against another or to teach students to hate their country,” Murray said.

Sara McDaniel, who identified herself as a professor and former K-12 teacher, took issue with Oliver’s expression of fighting for a “colorblind America.”

“The colorblind ideology is not what we’re going for anymore,” McDaniel said. “If I’m colorblind, I can’t see the beauty of (Rep. Rolanda Hollis, D-Birmingham) as a black woman, legislator and her lived experiences that have brought her here.”

McDaniel said the legislation pushes against difficult conversations that need to be had.

“Unfortunately for educators, students and families in Alabama, a group of all-white. almost all-male legislators have taken what is an opportunity for honest and difficult conversations about how to improve the educational experiences and outcomes for all Alabama students, and chosen instead to present a national political dog whistle, contributing to the current culture war and dragging us backward,” McDaniel said. “They have chosen politics over student wellbeing and performance, ultimately over the future of our state. Nothing in this bill has to do with reality in Alabama. Let me be clear, educators are not indoctrinating, inoculating or compelling assent from students. Some of you have bought into a manufactured crisis. What we have in the list of 11 so called divisive, although he said racist, concepts is veiled language intended to chill important conversations with students and educators regarding bias, history and racism.”

Corinn O’Brien, vice president of policy at A+ Education Partnership, said the bill would create more stress on teachers and could worsen the already urgent teacher shortage.

“It will place a difficult burden on our educators that are already stressed to the max,” O’Brien said. “Alabama is facing a major teacher shortage and COVID-19 has only increased this crisis. A recent poll showed that around a third of educators would consider leaving the field should laws similar to this one be enacted. And additionally, as educators try to navigate the new rules on what they can and cannot discuss in the classroom, they may avoid hard topics altogether to avoid serious consequences like losing their jobs. And that means that our students miss out on the opportunity to foster critical thinking like previous speakers have mentioned and altogether could lose an excellent teacher.”

The bill empowers the relevant agencies or schools to discipline or terminate teachers in violation fo the act.

Several speakers alluded to their lack of confidence that their comments would sway the minds of the committee.

“Regrettably, I harbor no illusion that my comments today will defeat passage of House Bill 312,” said Vanzetta McPherson, an attorney and retired federal magistrate judge. “But its passage would be a mistake. And I believe that when mistakes are willfully made, they should also be knowingly made.”

Educator David Carter said the bill is not based on any issues actually occurring in Alabama’s education system.

“This is a solution in search of a problem and it is not a good solution,” Carter said. “And there is not a problem.”

The bill will come back next week for public debate by the committee ahead of a vote on the bill.