A new report from Return My Vote, a nonprofit focused on restoring voting rights to Alabamians with felony convictions, reveals that Alabama’s so-called “moral turpitude” law disproportionately disenfranchises Black citizens—and makes it harder for them to reclaim their right to vote.

The findings, based on a three-year analysis of nearly 25,000 voter records, are laid out in a new report titled “Alabama’s Moral Turpitude Law Disproportionately Strips Black Citizens of Their Voting Rights.”

“The disparities are not just the result of over-policing or over-incarceration,” said Richard Fording, co-director of Return My Vote. “Black Alabamians are both more likely to be stripped of their voting rights and less likely to get them back. That’s a structural failure—rooted in policy, not just circumstance.”

The researchers obtained the data only after a federal judge ordered the Secretary of State’s Office to comply with a request from Greater Birmingham Ministries under the National Voter Registration Act. Former Secretary of State John Merrill had refused to release the records voluntarily.

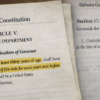

The data covers individuals purged from voter rolls or denied registration between 2017 and 2021—the first four years after Alabama passed the “Definition of Moral Turpitude Act,” which clarified which felonies would result in disenfranchisement.

While Black citizens make up about 26 percent of Alabama’s voting-age population, they accounted for 52 percent of those administratively disenfranchised. And despite their higher rates of removal, Black Alabamians were also 50 percent less likely than their White counterparts to have their voting rights restored. Similar gaps were found between men and women.

“This isn’t an accident—it’s an outcome,” said Dori Miles, the group’s other co-director. “The very system meant to define fairness is producing lopsided results.”

Even after accounting for disproportionate Black involvement in the criminal justice system, the report found that racial disparities in disenfranchisement persisted. “That means the law—and how it’s applied—doesn’t just reflect racial inequality. It reinforces it,” the report states.

Adding insult to injury, the researchers found vast disparities in how counties apply the law. Even when controlling for local arrest rates, some counties disproportionately removed voters from the rolls or denied registration.

Then came Alabama House Bill 100, passed in 2024, which dramatically widened the scope of disenfranchisement. The law made all inchoate felonies—including attempts, conspiracies and solicitations—disqualifying offenses. And it did so retroactively. While HB100 went into effect after the 2024 presidential election and isn’t reflected in the current dataset, researchers warned it could dramatically expand disenfranchisement moving forward.

“The full consequences of HB100 are still ahead of us,” said research assistant Maddie Minkoff. “But based on what we’ve already seen, we have every reason to be concerned.”

The report concludes that administrative discretion, vague statutes and outdated attitudes are converging to deny thousands of citizens—disproportionately Black, disproportionately male—their most basic democratic right.