Three hundred years ago this month, in a dockside community in the East End of London, John Newton was born. Following in his father’s footsteps, he would become one of the hordes of Englishmen who “go down to the sea in ships.”

Initially, he served on a commercial vessel, but while at port, he was “pressed” into service, or basically kidnapped, by the Royal Navy. The brutality of naval service was difficult, and Newton deserted his ship only to be captured and severely beaten in front of the crew. He was fortunate not to be summarily executed.

This experience initially drained him emotionally, but he was later emboldened to persevere and learn all he could about sailing. When Newton had conflicts with the captain of another ship, he was indentured to a native princess in Sierra Leone and treated as a slave.

Hearing of his son’s plight, Newton’s father launched a search, which eventually found him, freed him, and returned him to England. But even in all of this, he was never dissuaded from sailing and refused his father’s entreaties to become a planter in the New World.

Newton’s return to England was eventful and marked one of the most significant experiences in his life. When storms threatened his voyage home and tossed his ship in the ocean, he prayed that his life might be spared and bargained that if God would allow him safe passage, he would come to faith.

Not soon after his prayer, the storm stopped, and fair winds and following seas returned. Keeping up his side of the bargain, he began to read his Bible and renounced swearing, drinking and gambling. Newton marked this turn of events as a spiritual awakening and his conversion to Christian faith. He would celebrate the anniversary of this experience as the day he was born again and became a Christian.

Inasmuch as Newton gave up such obvious vices, generally condemned by priest and parishioner alike, there was one controversial aspect of his life that he retained—direct engagement in the slave trade.

Even after his conversion, roughly 10 years would pass before Newton would be persuaded that the buying and selling of humans was morally wrong and against his faith.

As a sailor, he saw firsthand the inhumane conditions of the trade, but he also profited from the lucrative trading system among England, Africa, and the New World. His active involvement captaining ships stacked with slaves as cargo would conclude when his health deteriorated from a stroke. But while not an active slave trader, he remained a financial partner in a business that profited greatly from the sale of slaves.

Eventually convicted that trading in slaves was sinful, Newton would renounce his former life, explaining that while he did experience a conversion, it took time for him to fully realize the inhumanity and brutality of slavery to change his heart and become a fierce advocate for its abolition.

No longer able to sail and completely disassociated from the slave trade, he was appointed the tax collector in Liverpool, which proved a lucrative position at it was a port city, and taxes in the forms of import duties increased as the trade of the British Empire grew.

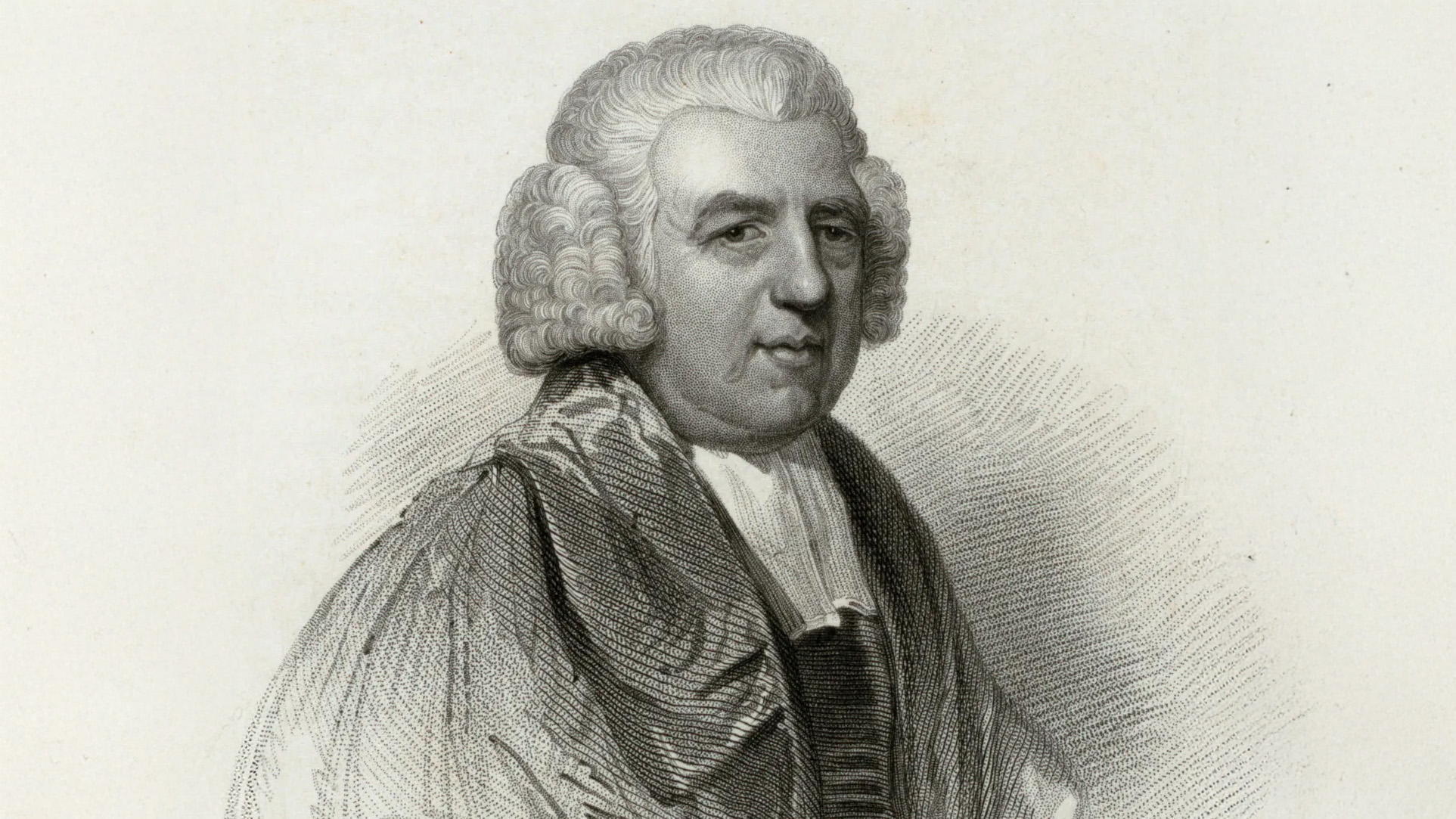

In his spare time, Newton studied the Bible and various works of theology, and, feeling a call to serve, he sought ordination as a priest in the Church of England. He was not immediately accepted and eventually became a lay minister after applying to other independent denominations.

He was an engaging preacher and his popularity attracted many people to hear his sermons. Eventually, Newton was ordained into the Church of England, but he continued his association with other denominations inspiring a tolerance for varying beliefs so long as the general tenets of the Christian faith were respected. His church added an extra balcony to accommodate crowds that came to hear him.

He inspired many who fell under his teaching and was a leader in the growing abolition movement of the late 18th century. William Wilberforce, a member of parliament, would seek Newton’s counsel on how faith should influence politics and was advised to use his position to support legislation for the abolition of slavery.

Publishing pamphlets and other articles explaining his experience with the slave trade and merging his religious convictions with politics, Newton developed a coalition that eventually enacted abolition.

Within a few months of the passage of the Slave Trade Act in 1807, Newton, who had long suffered from ill health and failing eyesight, died. He was buried in a crypt beneath the communion table at the Church of St. Mary Woolnoth.

His life’s work is perhaps best summarized by his most lasting legacy – authoring the hymn “Faith’s Review and Expectation” known popularly today as “Amazing Grace.” This hymn, sung by saint and sinner alike, is one of the most beloved in history. Estimates are that it is sung thousands of times each month in churches throughout the United States.

The influence of the hymn is so profound that it is celebrated even outside religious services as singers from every genre of music have recorded this song, performed it at concerts, and included it in their set lists. The power of the song is contained in the first verse and expresses Newton’s view of himself and his relationship to God. Only someone with his life experiences could publicly call himself a “wretch,” but only someone that low—and Newton had been there—could see the forgiveness in God’s grace as nothing short of amazing.

Newton’s early life was filled with humiliation and degrading moments. When close to death, he had been spared and realized his life had new meaning, but, even amid this righteous conversion, it took many years before he saw that slave trading was a wicked endeavor.

Once he was convinced of this evil, Newton’s status as a wretch was confirmed and made the gift of extraordinary grace — God’s unmerited favor toward him—even more pronounced.