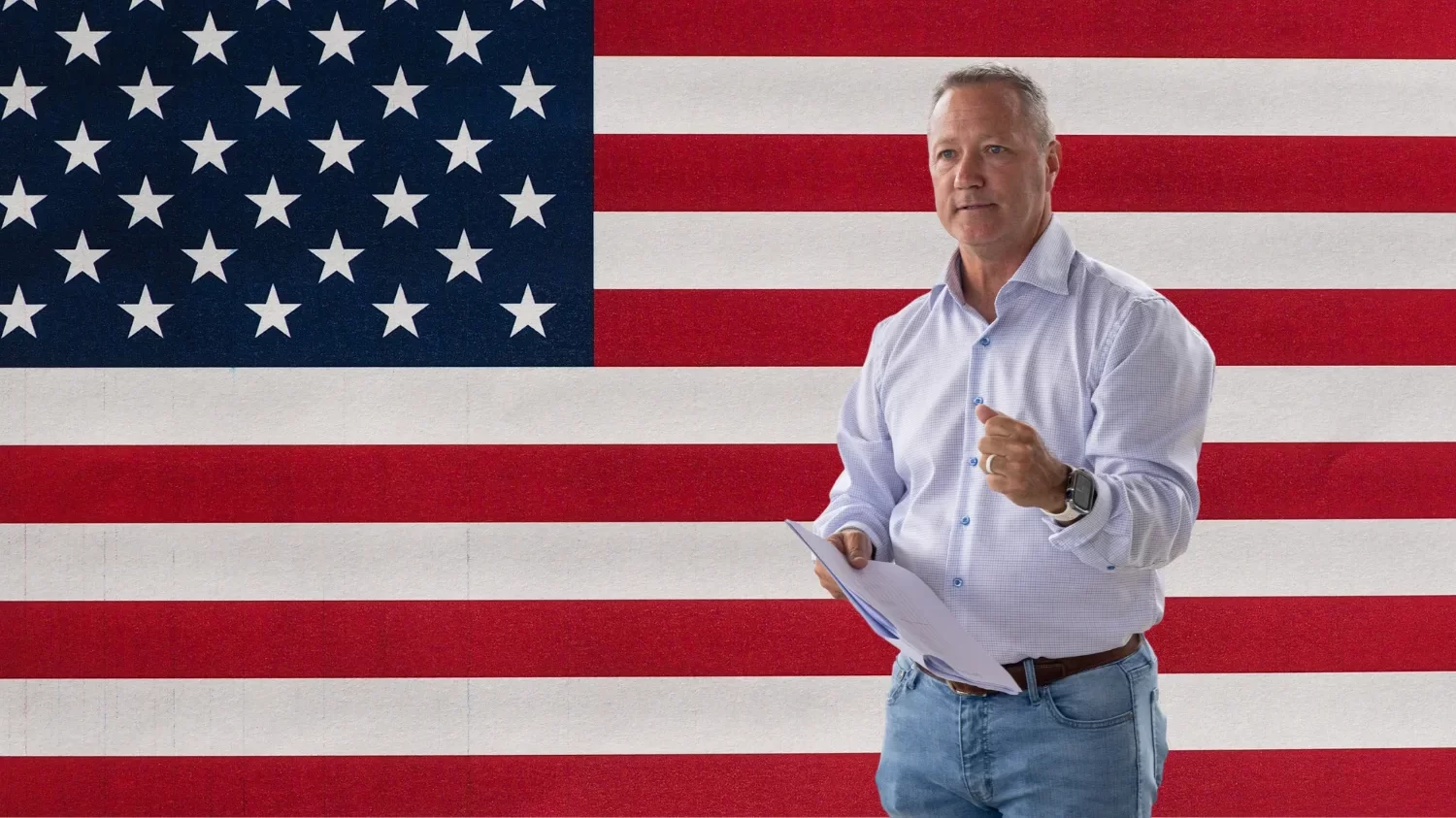

In campaign ads and stump speeches, Dustin Beaty presents himself as a casualty of the opioid crisis, a man who stumbled into addiction, lost his business and now seeks redemption in politics. It is a tidy story of struggle and survival. But in the files of the Alabama State Board of Pharmacy, and in the recollections of the investigators who tracked him, a very different picture emerges: not of a victim, but of a supplier.

Over the past several weeks, APR spoke with dozens of Walker County residents, law enforcement officers, other pharmacists and people who had firsthand knowledge of Beaty’s 2009 case before the Pharmacy Board. All persons interviewed were granted anonymity to speak freely, as law enforcement sources were not authorized to comment publicly on the matter. Together, their accounts—combined with legal filings—draw a portrait far removed from the narrative Beaty now tells.

According to narcotics investigators who worked Walker County at the time, Beaty was already on their radar before federal authorities stepped in. “We had been up on him for a good little while, and we knew that he was very likely the source of some of the things we found,” one former narcotics officer told APR. Another recalled raids where they uncovered giant, 1,000-count pharmacy bottles of opioids. “We knew at that point that we likely had a pharmacist involved because no thefts had been reported by pharmacies,” the investigator said. “We were building a case but just couldn’t get a solid, reliable informant that we could use … (before) the feds came in.”

A federal audit later found that Beaty’s pharmacy could not account for thousands of controlled pills, according to investigators who reviewed the audit. They told APR they believed it confirmed what they had long suspected: that opioids were flowing directly out of Beaty’s pharmacy into the community.

The scope of even the legally sold opioids is staggering. Beaty’s pharmacy, Hospital Discount Pharmacy, was one of the top opioid sellers in the country for a six-year period, according to DEA data made public in 2018. Between 2006 and 2012, the pharmacy distributed more than 5 million opioid pills—enough for every man, woman and child in Walker County to receive at least 11 pills per day for those six years. And while those pills were flooding out, Walker County was paying a terrible price. Between 2008 and 2017, the county recorded at least 250 opioid-related deaths and thousands of overdoses.

The Pharmacy Board’s Consent Order makes the record plain. The official file—IN THE MATTER OF DUSTIN J. BEATY, LICENSE NUMBER: 13754, BEFORE THE ALABAMA STATE BOARD OF PHARMACY, and HOSPITAL DISCOUNT PHARMACY, PERMIT NUMBER: 102015—charges Beaty with, among other violations, “selling, furnishing, giving away delivering or distributing unknown amounts of Methadone, Oxycontin, Hydrocodone and/or Norco to (four named individuals) and/or to persons unknown to the board.” He was also cited for “failing to maintain inventories and records of controlled substances,” for theft of cash from Hospital Discount Pharmacy, and for “allowing/assisting unlicensed persons to practice pharmacy.”

Confronted with that evidence, Beaty struck a deal. The Consent Order shows that while he and his business denied the allegations “for all legal purposes other than this proceeding,” they stipulated that the Board could present sufficient evidence to prove them. Based on that stipulation, the Board found Beaty guilty of multiple violations of state pharmacy law. His license was suspended for ten years, he was fined $12,000, and he was required to sign a decade-long monitoring contract. He was barred from managing or operating a pharmacy, prohibited from being present in any prescription department, and stripped of the right to hold keys to any pharmacy. His business was suspended for ten years and fined another $11,000. He waived all rights to a hearing or appeal, signing voluntarily and acknowledging he fully understood the order.

For reasons that remain unclear, Beaty was reinstated after just five years, even though his suspension was set for ten. His license was returned, but he remained under a monitoring contract for the full decade. A former Alabama Pharmacy Board employee told APR that while such agreements were common during the height of the opioid epidemic, Beaty’s case was “a bit unusual because of the clear evidence that he was also selling opioids illegally.” That, the source explained, was likely why his suspension was originally set at ten years, when most were five.

This is not the paperwork of a man who was merely an addict. It is the record of someone who, according to investigators and the Board’s own findings, profited from the crisis in his community and avoided criminal prosecution through a carefully negotiated arrangement.

Despite this, Beaty has recast himself as nothing more than a victim. But omission is not repentance. He initially agreed to sit down with APR, only to go silent when the time came, ignoring calls and messages. His refusal to answer leaves a series of questions that voters deserve to hear addressed. Were you really an addict, or was that your shield against trafficking charges? How many pills did you sell, and what did you do with the money? Why did DEA audits show your pharmacy could not account for thousands of opioid pills? How did you win back your license in half the time most others served? And beyond the illegal sales, how do you justify the more than 5 million opioid pills your pharmacy dispensed in just six years?

These questions remain unanswered. And Beaty’s silence speaks louder than his campaign ads. Walker County has paid dearly in the opioid crisis. Families continue to bury loved ones, neighborhoods continue to carry the scars, and the crisis is still raw. In that reality, Beaty’s carefully curated story of redemption is more than incomplete—it is misleading. He wasn’t just swept up in the epidemic; by the record of his own admissions, DEA data and the Board’s findings, he helped fuel it. Redemption in politics, as in life, begins with the truth. If the Board’s own record shows he was selling opioids into his community, can voters really believe he was only a victim—and not also a supplier?