There are moments when a state’s criminal justice system reveals more about those who operate it than about the people it seeks to punish. Alabama is living through such a moment now, and Attorney General Steve Marshall, who is campaigning for the United States Senate, has decided that the machinery of execution is the best place to showcase his political toughness.

The result is a disturbing pattern in which the pursuit of death has eclipsed the pursuit of justice.

For years, Alabama’s lethal injection protocol has been a national scandal—not because the death penalty itself is uniquely controversial here, but because the state repeatedly failed to carry out executions without inflicting prolonged and visible suffering. Execution teams spent hours probing for veins, puncturing arteries, and abandoning procedures midstream. Responsible leadership would have treated those failures as a moment of reckoning. Marshall treated them as a reason to press harder.

When lethal injection faltered, he championed nitrogen hypoxia, a method of killing no democracy on earth uses. Witnesses described convulsions, shaking and gasping for air—the unmistakable signs of conscious distress—during Alabama’s first nitrogen execution. The United Nations warned that the method may constitute torture. Veterinary guidelines prohibit its use on animals.

Yet Steve Marshall called the procedure a success and urged other states to adopt it.

This enthusiasm for experimentation reveals something fundamental about the way power is being exercised in our state. Under Marshall, the death penalty has become less a legal instrument than a political performance. The question is no longer whether Alabama can impose the ultimate punishment constitutionally or humanely, but whether the attorney general can project maximum ferocity while doing so.

That dynamic is fully exposed in Hamm v. Smith, now before the U.S. Supreme Court.

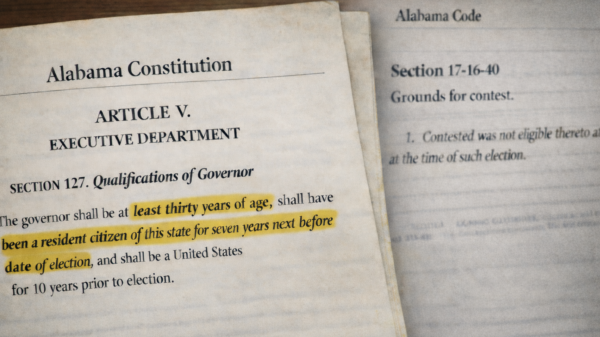

Joseph Clifton Smith is guilty of the crime he committed, but he has documented intellectual disabilities dating back to childhood. That fact—long established and medically supported—cannot be brushed aside simply because the state wants an execution. He took five IQ tests, scoring between 72 and 78. He read at a fourth-grade level, spelled at a third-grade level and performed math at a kindergarten level. His entire educational history reflects significant cognitive limitations. Under Atkins v. Virginia and Hall v. Florida, executing a person with such deficits is unconstitutional.

Yet Alabama insists that only Smith’s highest IQ score should matter—discarding the others, along with the clinical evidence of disability, because that single number serves the state’s desired outcome.

But during oral argument, skepticism came not only from the Court’s liberal wing but from conservative justices Alabama assumed would be firmly in its corner.

Justice Samuel Alito, often a champion of the state in criminal cases, warned that Alabama’s standard risked creating “a situation where everything is up for grabs,” acknowledging the instability and chaos that would follow from reducing intellectual disability to a single datapoint.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh questioned how Alabama’s “highest score wins” rule could coexist with Hall, which explicitly rejected rigid IQ cutoffs. Disability, he noted, “requires more than just a number.”

Chief Justice John Roberts pressed Alabama’s solicitor general on why the state elevates one IQ score “over an entire clinical history,” a quiet but pointed recognition that Alabama’s cherry-picking distorts both law and science.

And in the most striking exchange, Justice Neil Gorsuch suggested the state’s approach might “eliminate the protection” the Court recognized in Atkins—in other words, that Alabama’s rule nullifies the Eighth Amendment safeguard entirely.

When even the Court’s conservative bloc expresses doubts, the fault lies not with the law but with those attempting to bend it beyond recognition.

This should not surprise us. The founders feared the unrestrained use of state power. James Madison wrote that government “is the greatest of all reflections on human nature,” and must therefore be hemmed in by structure and principle. William Blackstone insisted that when facts are uncertain, “the law should incline toward mercy.” Cesare Beccaria, whose writings shaped the Eighth Amendment, warned that cruelty is “the surest sign of a weak government.”

Even the English Bill of Rights of 1689—the ancestor of our own constitutional protections—prohibited “cruel and unusual punishments,” an admonition meant to check rulers who confused power with righteousness.

Steve Marshall’s approach defies every one of these principles.

It is also out of step with the country. More than half of U.S. states have halted or abolished the death penalty. Only three have even contemplated nitrogen executions, and Alabama is the only one that has carried them out. Instead of learning from national caution, Marshall has made Alabama ground zero for experimental killing.

That is not leadership. It is political theater at the expense of human dignity.

A quiet truth hangs over this moment: cruelty has become a form of signaling in certain corners of American politics—a way to demonstrate allegiance, not seriousness. Marshall is not operating in a vacuum. His posture reflects a broader pattern in which punishment becomes performance and constitutional restraint becomes optional when it interferes with ambition.

A state’s power to take a life is the most solemn authority it possesses. It demands humility, caution and fidelity to the Constitution. Alabama today displays none of those virtues. Under Steve Marshall, the state’s death machinery has become a stage on which to act out political toughness, even as the law urges restraint and the facts plead for mercy.

The founders designed a republic, not a killing machine. They believed that a nation’s character is revealed not by how fiercely it punishes, but by how carefully it restrains itself when punishment is within reach. They understood that power without moral limits eventually devours the very principles it claims to defend. And they trusted that future leaders would inherit not only their laws, but their wisdom.

That trust is being tested in Alabama.

If we allow ambition to outrun decency—if we accept cruelty as competence and spectacle as justice—then we are not merely bending the Constitution. We are hollowing out the moral core that gives it meaning. What remains afterward is not a republic, but its shadow.

Alabama must choose whether we stand with the principles that built this nation… or with the politics now threatening to undo them.