Election after election, most citizens sit out the process. Turnout remains low. Districts are drawn so safely that outcomes are rarely in doubt. Straight-ticket voting replaces deliberation. And a quiet but corrosive belief takes hold: my vote doesn’t matter.

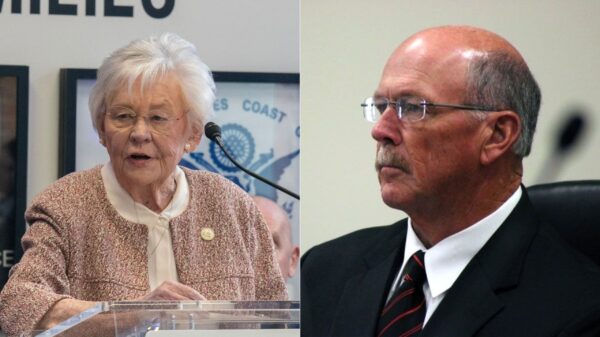

The result is not representative government. It is selection by a minority, power exercised without meaningful consent, and leadership insulated from accountability.

That is not how self-government is supposed to work.

When citizens disengage, they do not preserve their freedom. They relinquish it—often without realizing they have done so. Choices do not disappear when people stop making them. They are simply made by someone else. In that vacuum, control replaces representation, habit replaces judgment, and power consolidates not because it is demanded by the people, but because it is no longer challenged by them.

This is not merely a structural problem. It is a moral one.

A society that loses the habit of participation also loses the habit of responsibility. When people stop choosing, they stop practicing judgment. Over time, that atrophy shows itself not just at the ballot box, but in civic life itself—fewer questions asked, fewer expectations placed on leaders, fewer consequences when authority is abused. What replaces engagement is not peace, but passivity. And passivity has never been a stable foundation for freedom.

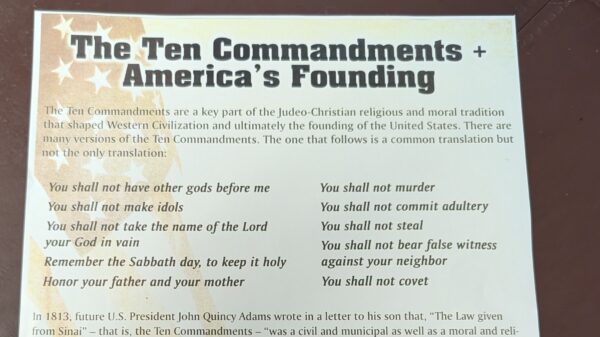

Alabama has lived under one-party rule long enough to test the argument that dominance produces stability or progress. It has not. What it has produced instead is drift—away from the realities of daily life, away from the way most people actually live, work and think. Freedom is increasingly shaped through a narrow ideological lens that does not reflect the complexity of real communities. Choice is constrained in the name of doctrine. Autonomy is filtered through politics. Government no longer responds to the people so much as it instructs them.

Survey after survey shows that a majority of Alabamians believe Montgomery does not care about them. That is an extraordinary indictment of a democratic system. But the deeper question is not whether people feel ignored. It is whether they are willing to act on that belief. Resignation has replaced resistance. Frustration has replaced organization. People sense something is wrong, but too many have accepted it as inevitable.

For many Alabamians, disengagement does not look like apathy. It looks like exhaustion. It is the feeling that decisions are made long before a ballot is cast, that power circulates among the same names, the same donors, the same insiders, regardless of public sentiment. When participation feels symbolic rather than consequential, people stop seeing themselves as citizens and start seeing themselves as spectators. Democracy does not collapse in that moment, but it thins. It becomes procedural rather than participatory, a system that functions without fully listening.

None of this is irreversible. It is only entrenched by silence.

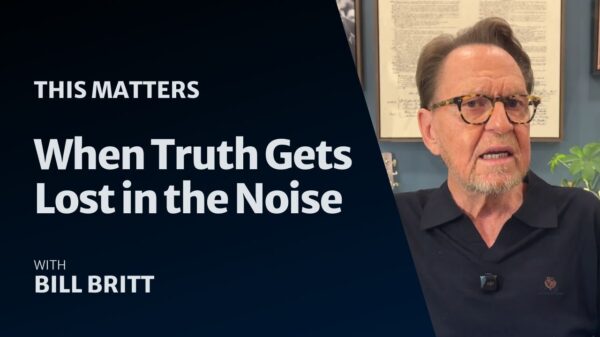

More than two centuries ago, Thomas Paine understood something essential about free societies. He warned that long habit could make injustice appear normal, that people could grow so accustomed to being ruled that they forgot they were capable of ruling themselves. Freedom, he believed, did not survive on slogans or sentiment. It survived on participation, judgment and the refusal to accept authority simply because it existed.

But Paine was not cynical about the people. He trusted them. He believed ordinary citizens were capable of extraordinary responsibility—if they were spoken to honestly and treated as adults. He appealed not to anger, but to dignity. He called people upward, not inward.

That lesson remains painfully relevant.

Alabama has always been a conservative state. What we are witnessing now, however, is not conservatism in its traditional sense. True conservatism once emphasized restraint, skepticism of concentrated power, respect for individual conscience, and humility in governance. What has replaced it is something closer to a nationalized political machine—more interested in dominance than deliberation, conformity than conscience, power than good government.

This is not a call to abandon conservatism. It is a call to remember it.

The modern version would be unrecognizable to those who believed government exists to serve society, not command it, and that liberty is protected not by enforcing uniformity, but by limiting power. Conservatism was never meant to insulate leaders from accountability. It was meant to keep authority answerable to the people.

Every generation inherits a choice it did not create but must still answer: whether to accept the politics it is handed, or to insist on something better; whether to be governed by habit, or by conscience.

Self-government does not fail all at once. It fails slowly, when people decide the effort is no longer worth the trouble.

Voting for individuals instead of labels requires work. It requires attention. It requires the willingness to ask who actually understands your community, who respects your autonomy, and who believes government answers to the people rather than the other way around. That responsibility cannot be outsourced. It never could be.

The question facing Alabama is not whether Montgomery cares.

The question is whether the people of this state are ready—once again—to take responsibility for the power that has always belonged to them.