There was a time when the word conservative meant something specific—and something serious. It did not mean rage, or spectacle, or a politics built around humiliating one’s opponents. It was not driven by resentment or by the endless need to “own the Left.”

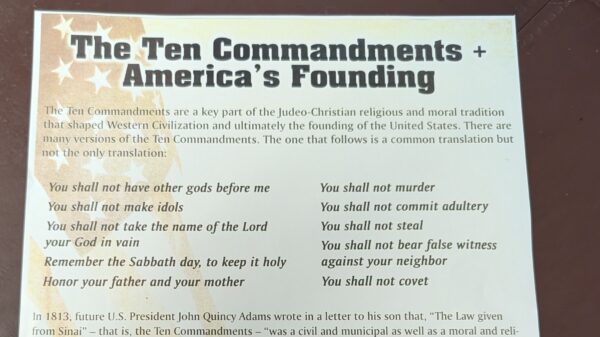

Traditional conservatism—the kind shaped by thinkers like John Locke and Edmund Burke—rested on an older and deeper truth: freedom survives only when it is anchored to responsibility, moral restraint and respect for the institutions that hold a society together.

Locke taught that government exists for one central purpose—to secure the natural rights of its citizens: life, liberty and property. But he also understood that liberty without order eventually dissolves into chaos. So government must be limited, its powers checked and its actions accountable to the people. Civic virtue—the moral discipline to govern oneself—was not optional. It was the foundation of a free society.

Burke added another layer: a healthy society changes, but it changes gradually. Real conservatism meant humility in the face of history—the belief that the past carries wisdom, and that institutions like law, education, faith, community and a free press are not enemies to be conquered, but pillars to be stewarded and improved.

It was not a politics of adrenaline. It was a politics of stewardship.

Conservatives once argued that power—especially their own—should be restrained. That character mattered. That truth mattered. That governing required trade-offs, compromise, patience and the unglamorous work of making the country function a little better than it did yesterday.

They defended the very institutions that make self-government possible—courts, universities, public service, lawful elections—not because those institutions were perfect, but because without them the alternative is chaos, corruption, or eventually, tyranny.

And it is important to remember that American political movements have never been static. Parties evolve, coalitions shift, and ideologies reform themselves over time. Jackson’s Democrats once claimed the populist mantle. Lincoln’s Republicans were the party of union and national purpose. In the last century, both parties repeatedly re-sorted themselves around labor, civil rights, religion and economic change. So the problem is not that politics evolves—it always has.

Our two-party system has never been perfect. The parties have reshaped themselves again and again over time. At their best, that rivalry produces balance and restraint. At their worst—as some believe we see today—it hardens into paralysis and chaos.

And that question—whether change strengthens or weakens the civic foundations of a free society—feels especially urgent now.

Because increasingly, what calls itself the Right is not a philosophy of ordered liberty, but a politics organized around resentment. The work of governing is displaced by politics as stagecraft. Conflict becomes the point. Truth becomes something to be arranged rather than honored. And winning is measured not by whether life improves for ordinary people, but by whether one’s opponents can be publicly shamed and driven from the field.

Layered on top of that is a counterfeit populism.

Historically, populism challenged concentrated power on behalf of ordinary people. It pushed back against systems that rigged the game—monopolies, financial conglomerates, political machines—so that working families might have a fair chance.

Much of today’s “populism” is something else entirely. It borrows the cadence of working-class anger, yet its policies concentrate wealth upward. It rails against “elites,” while shielding corporate power and privilege from real accountability. It claims to speak for the forgotten American, while advancing an economic order that continues to reward the few.

The language is democratic. The outcomes are aristocratic.

That is not populism; it is a politics of resentment dressed up as reform. It converts legitimate public frustration into a permanent state of agitation, while the structural burdens people face—healthcare costs, wages, opportunity—remain largely unchanged.

This is not conservatism either. It is reaction—politics driven by injury rather than guided by principle.

Traditional conservatism believed that character and virtue mattered because power without restraint eventually consumes the society it claims to defend. It understood that a nation cannot endlessly attack its own institutions and expect them to stand. It recognized that democracy depends on leaders who can lose honestly, disagree honorably and tell their supporters the truth—even when the truth is inconvenient.

That doesn’t mean the conservatives of the past were always right—they weren’t. But the best of the conservative tradition at least tried to conserve something worth keeping:

Law. Order. Truth. And the dignity of public life.

Today, too many politicians waving the conservative banner conserve nothing. They burn through institutions, norms and trust like dry tinder—and then campaign on the fire they helped ignite.

America needs a principled conservative movement—one that values liberty and law, markets and opportunity, tradition and reform where needed. But that requires leaders who are interested in governing rather than staging conflict, in character rather than celebrity, in service rather than perpetual combat.

Because in the end, a nation cannot survive on anger alone. Sooner or later, someone has to do the work.

And that—more than the outrage of the moment—is what truly matters.