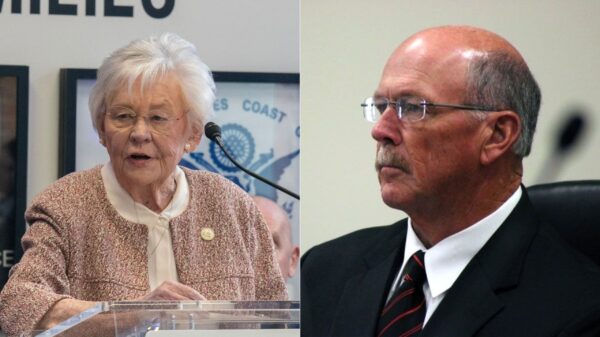

U.S. Senator Tommy Tuberville, who currently leads Republican primary polling in the race for Alabama governor, has once again drawn controversy for his remarks about Islam and his broader campaign against what he calls “Sharia law.” The latest flash point came after New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani took his oath of office on a Quran.

Tuberville responded on social media with a six-word declaration: “The enemy is inside the gates.”

The language is striking. It does not simply disagree with Mamdani’s political agenda. It frames the presence of a Muslim elected official inside American civic life as infiltration—Islam not as one religion among many protected by the First Amendment, but as a civilizational danger. In that framing, the line between peaceful religious practice and extremist ideology disappears. The faith itself becomes the threat.

CAIR renews invitation to Tuberville

Following Tuberville’s recent post, the Council on American-Islamic Relations–Alabama reiterated that its invitation remains open for him to visit a mosque and speak directly with Muslim Alabamians—citizens who live, work, and raise families under the same Constitution as everyone else in this state. The group has also emphasized the constitutional principles at stake. In a recent statement responding to Tuberville’s rhetoric, CAIR National Deputy Director Edward Ahmed Mitchell said that “anyone is free to believe that something is superior to something else and you cannot punish them because of their thoughts that you don’t like. That’s a very basic First Amendment principle.”

Tuberville, for his part, has framed his rhetoric and proposed federal legislation as a defense of what he calls American and constitutional values. He has argued that Islamic law is incompatible with Western democracy and must be rejected wherever it might take root. That argument underlies his push to “ban Sharia law” from American courts—a stance he has reiterated as he campaigns for governor.

What the law already says

But here the law is already clear. American courts cannot enforce any rule—foreign, religious, or otherwise—that conflicts with the U.S. Constitution. That has always been true under the Supremacy Clause.

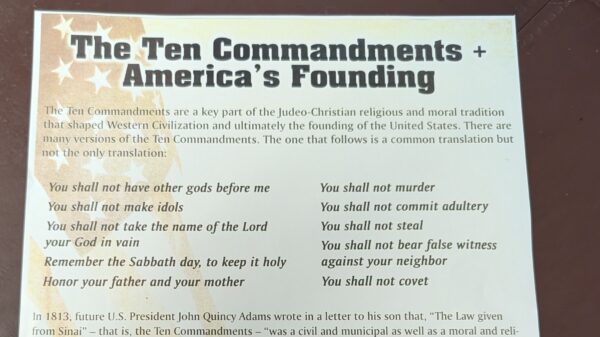

Alabama has already been through this debate. In 2014, voters approved a constitutional amendment—often referred to as the “American and Alabama Laws and Alabama Courts Amendment”—that prohibits state courts from applying foreign or religious law if doing so would violate constitutional rights. In practice, the amendment largely reaffirmed existing law. Courts were already barred from applying any rule that conflicted with the Constitution.

It is telling how carefully that amendment was drafted. Earlier efforts in other states had attempted to ban “Sharia law” explicitly. The most prominent example came in Oklahoma in 2010, when voters approved the so-called “Save Our State” amendment, which singled out Islamic law by name. That measure never took effect. A federal court blocked it, ruling that it unconstitutionally targeted one religion, in violation of the First Amendment. Oklahoma later shifted—as Alabama did—to broader “foreign law” language that does not name Islam at all.

The lesson is straightforward. When legislation singles out Islam, it runs headlong into the Constitution’s ban on religious discrimination. When the language is broadened to include all foreign or religious law, it merely restates the principle that courts may not apply any rule that violates constitutional rights.

Law that doesn’t change—rhetoric that does

So Tuberville’s proposals do not meaningfully change American law. Courts remain bound to the Constitution, as they always have been. What his rhetoric changes is the cultural meaning of belonging—who is presumed to fit comfortably inside American civic life, and who is not.

CAIR-Alabama has warned that framing matters. In a statement responding to Tuberville’s anti-Sharia bill, one of the organization’s attorneys argued that the proposal could “provide the government with the pretext to target and discriminate against Americans who are simply abiding by the tenets of their faith.” The concern is not that courts will suddenly begin enforcing Islamic jurisprudence. They will not. The concern is that an entire faith community may increasingly be treated as inherently suspect inside its own country.

Motive is unknown—pattern is clear

We cannot know, and should not claim to know, what Tuberville privately believes. Motive is internal. But we can observe the pattern. His rhetoric consistently casts Islam as adversarial. His legislation echoes that message, even while restating legal protections that already exist. And his language leaves little room for the idea that Muslim participation in civic life is compatible with the American constitutional order.

There is also political reality. Since 9/11, a current within conservative politics has treated Islam not only as a religion but as a competing civilization. That message continues to resonate with some Republican primary voters who view immigration and cultural change as existential threats. Anti-Sharia rhetoric rarely alters the law, but it sends a strong symbolic signal about identity and belonging.

Where the constitutional tension lies

The First Amendment does not recognize preferred and suspect faiths. It guarantees free exercise of religion and government neutrality toward belief. When a sitting U.S. senator and leading gubernatorial contender responds to a Muslim official swearing an oath on a Quran by declaring, “The enemy is inside the gates,” the question is not merely legal. It is civic.

Do we still understand the Constitution as a covenant broad enough to include all faiths equally—or only those that rest comfortably within majoritarian culture?

CAIR’s renewed invitation is therefore more than politeness. It asks Tuberville to meet Muslim Alabamians as citizens rather than as abstractions—to see the people behind the rhetoric.

Whether his language grows out of conviction, political calculation, or some mixture of both, the practical effect is the same: Islam is treated as a standing threat rather than a faith practiced under the same constitutional guarantees as any other. That may serve a short-term political narrative. It does little to strengthen the civic culture the rest of us rely on—the one that insists the Constitution belongs to every citizen in equal measure.