After school let out for the summer of 1959, 14-year-old Wendell Paris rode his motorcycle daily through the streets of Tuskegee, Alabama.

On one particular afternoon, another Black teen he did not know cussed Paris out as he rode by, seemingly envious that Paris had a motorcycle.

Paris cussed back at him.

Later that day, the same teen came to Paris’s house, knocked on the door and asked Paris to help him find a stolen bicycle that belonged to his younger brother.

Paris agreed to help the teen, Samuel Younge Jr., age 15, and together they rode all over Tuskegee, taking turns driving the motorcycle as they looked for the stolen bicycle.

The two boys became fast friends that afternoon and would go on to high school and college—until January 3, 1966, when Younge was shot and killed by a 67-year-old gas-station attendant, a white man named Marvin Segrest. While a Macon County grand jury indicted Segrest later that year, the trial was moved to Lee County, where an all-white, all-male jury acquitted Segrest.

Younge’s murder on January 3, 1966, was a formative moment for Paris. He made a decision that would define the rest of his life.

“I decided that night that I would fight injustice until I die,” Paris said.

Sixty years later, in December 2025, in an interview at New Hope Baptist Church in Jackson, Mississippi, Paris recalled fond memories of his friendship with Younge and the impact of their work in the civil rights movement.

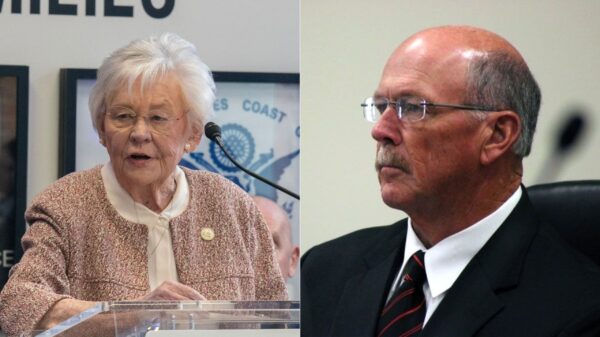

Revered Wendell Paris at New Hope Baptist Church in Jackson, Mississippi, holding a copy of Sammy Younge Jr.: The First Black College Student to Die in the Black Liberation Movement. (Liz Ryan for APR)

Teen years in Tuskegee

At first, the friendship between Wendell Paris and Samuel Younge Jr. was based on wheels. Both teens enjoyed riding on Paris’ motorcycle. They also loved cars.

Paris recalled many occasions during the summer of 1959 that he and Younge would take Younge’s aunt’s car for a drive around Tuskegee. Younge’s aunt, Lottie Waddell, a language professor at Tuskegee Institute, left her car with her older brother, Younge’s father, while she and her husband, Dr. William Waddell worked with Native people in North Dakota.

Younge borrowed a key to the car and rode with Paris on his motorcycle to retrieve the car from a lot for the afternoon.

The teens made sure to return the car by 4:15 p.m. so that it could cool off before Younge’s father arrived home. That way, Younge’s father would not know that they had taken the car out for a drive.

The teens had so much fun during that summer that Younge did not return to the all-male, college prep boarding school, Cornwall Academy, over 1,000 miles away in Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

Instead, Younge joined Paris at Tuskegee Institute High School in the fall of 1959.

In 1961, Paris graduated from high school at age 16 and started college at Tuskegee Institute, studying agriculture.

The following year, Younge graduated from high school.

However, instead of entering college after high school, Younge joined the U.S. Navy. Stationed in Portsmouth, Virginia, Younge was to serve aboard the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Independence. Three months into his service, Younge’s ship engaged in the naval blockade of Cuba, a successful strategy proposed by President John F. Kennedy’s administration to halt a potential nuclear disaster with the Soviet Union, widely known as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

While Younge had enlisted in the Navy for a three-year term, medical issues prevented him from completing his commitment. In September 1963, doctors responded to Younge’s complaints of severe pains in his abdomen by removing one of his kidneys. Weeks later, doctors effectively responded to Younge’s continued complaints of intense pain and saved his other kidney.

With only one kidney, however, Younge could not continue his tenure in the Navy. After another few months, the Navy discharged Younge in July 1964.

During the subsequent six months, Younge worked as a nursing assistant where his father was employed at the VA hospital in Tuskegee, established in 1923 as the first federal hospital entirely staffed by Black veterans to serve Black veterans.

Students turned movement activists

In January 1965, Younge joined Paris at Tuskegee Institute as a freshman with an interest in studying political science.

Paris and Younge both became active in the Tuskegee Institute Advancement League, TIAL, an organization founded in 1964. TIAL was a local group that worked collaboratively with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC, a grassroots organizing group of young activists dedicated to confronting segregation through peaceful, direct action protests across the U.S. South.

The TIAL office was located in downtown Tuskegee at 300 Fonville Street in a duplex with a shoe shop. “We had a mimeograph machine and a telephone, and a very small desk and some chairs,” said Paris. “We would stay at the TIAL office at night.”

TIAL issued a bi-monthly student newspaper, The Activist, to which both Paris and Younge contributed articles and assisted in publishing.

“Why are there over 100 percent registered white voters?” wrote Paris in his essay, “The Poor of Macon County,” in the first issue of The Activist.

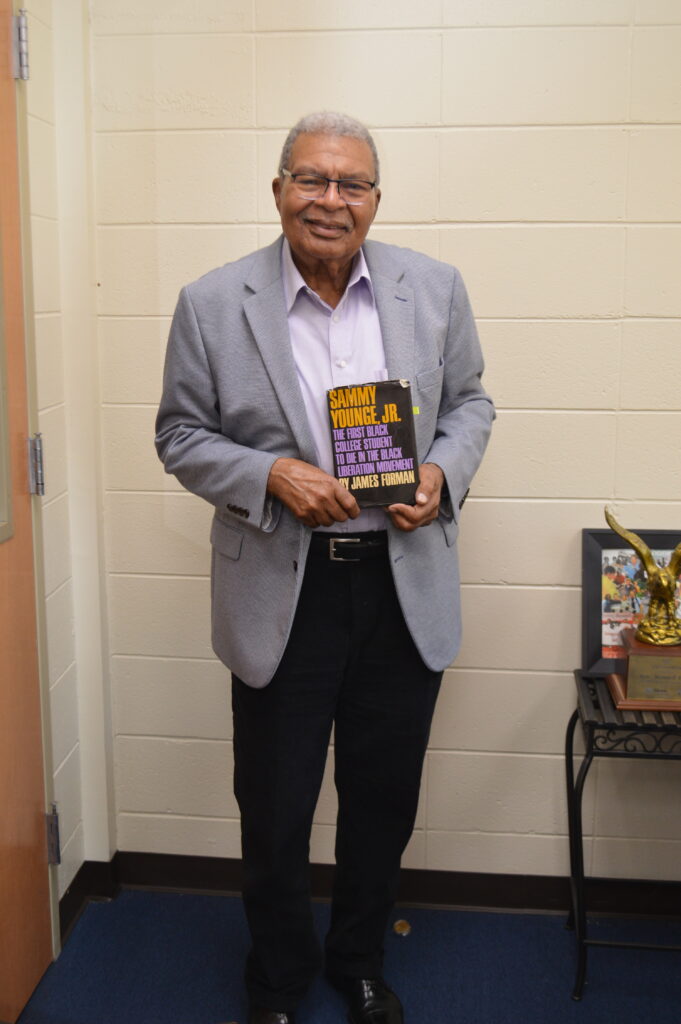

On March 10, 1965, Paris and Younge attended a protest in Montgomery, with 700 other activists, where they met SNCC Chairman James Forman, who later wrote a book about Younge, Sammy Younge Jr.: The First Black College Student to Die in the Black Liberation Movement.

One of the most memorable direct actions that Paris and Younge participated in was their trip to Ruleville, Mississippi, during Easter vacation in late April 1965 to assist with a voter registration campaign.

In Ruleville, they worked under civil rights leader and grassroots community organizer, Fanny Lou Hamer, who’d requested assistance from the students on the upcoming municipal elections on May 11, 1965.

“We helped Mrs. Hamer to register about 200 people there in two weeks time,” said Paris.

Paris recalled the two-week stint with Hamer vividly.

While Paris and Younge were having breakfast in her home, Hamer opened a window shutter and pointed out the hospital across the street from her house. She told them that if she ever became ill, not to take her to that hospital, but to take her to the Black hospital in Mound Bayou, some 30 miles away. Hamer told Paris and Younge that Black women who went to that hospital returned sterile.

“She was one of the greatest community organizers I’ve run across because she was so ingrained and devoted in the community,” said Paris. “She was a natural genius.”

Paris and Younge learned other lessons from that trip, including how to evade klansmen while on the backroads of the Deep South. One of the student activists whom klansmen shot and injured while he’d gotten into his car in Mississippi advised them to remove the light bulb from the interior dome light in their car.

“You take the light bulb out of that dome so that you won’t give folks a clear shot at you,” said Paris.

After classes ended in May 1965, Paris and Younge spent the summer working on TIAL’s voter registration drives, including the first “Freedom Day” in Brownsville. Located 17 miles from Tuskegee, Brownsville was targeted by TIAL because Black people there owned their own land, which meant that they didn’t have to face retaliation from white landowners for registering to vote.

Paris recalled that he and Younge assisted more than a hundred people to vote on the first day of the drive.

That action not only upset the Macon County clerk’s office but also the Tuskegee Civic Association, TCA, a Black-led organization. The Macon County clerk and TCA had an agreement not to bring more than 12 people a day to register to vote.

“We had to tell him, we didn’t make that agreement,” said Paris about his conversation with the Macon County clerk. “We’re here with 100 people today.”

Later that summer, Paris and Younge led efforts to integrate Tuskegee’s churches. After one direct action at a church, alleged Klan leader and Pat’s Cafe owner, Ossie Ross, hit Younge with a .32-caliber gun on the side where doctors had removed Younge’s kidney. Another man hit Paris in the head, where a scar still shows the blow.

As Paris and Younge worked to desegregate institutions in Tuskegee and registered more voters throughout the summer, that impacted the political balance in the city among Black and white leaders. “They saw us as a threat because here we were messing up that ‘model city’ image,” said Paris.

Paris’ parents were supportive of his participation in the movement, even attending and speaking out at movement meetings.

At a mass meeting called after Paris and Younge were injured while trying to desegregate a church, Paris recalled his father speaking out in favor of Paris, Younge and other movement activists to urge them to allow the youth to continue to engage in civil rights activities.

In retaliation for Younge’s civil rights activism, klansmen made anonymous phone calls to Younge’s mother, threatening to bomb her house. In response, Younge moved from his residence on the Tuskegee Institute campus back to his parents’ home. Younge made the move to protect his mother and younger brother, especially as his father was out of town during the week, having taken a job in Atlanta as a group relations specialist in the U.S. Forestry Service.

Over the subsequent two weeks, additional support watching the Younge’s home came from the Deacons for Defense, a self-protection group founded in 1964 by Black World War II veterans with 20 chapters across Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana.

In the fall, Tuskegee Institute officials placed Younge on academic probation due his low grades during the previous semester and advised him to focus on his studies rather than on his civil rights activities.

Despite the warning, Younge continued his involvement in civil rights activities along with Paris.

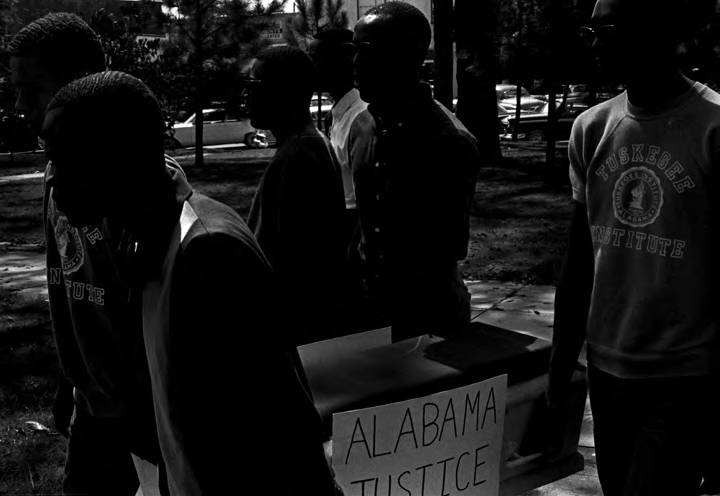

Tuskegee Institute students carrying a mock coffin with a sign “Alabama Justice’ in reaction to the Lowndes County jury’s acquittal of Tom Coleman in the death of civil rights activist Jonathan Daniels. (Alabama Department of Archives and History/Jim Peppler/Southern Courier)

Fall 1965

One of the direct actions that Paris, Younge and members of TIAL organized in October 1965 protested the acquittal of Thomas Coleman for the murder of civil rights activist Jonathan Daniels, a 24-year-old white Episcopal seminarian in Hayneville, Alabama.

Activist Gwen Patton wrote about this direct action in her book, My Race to Freedom: A Life in the Civil Rights Movement, stating that Younge wrote out the words “Alabama Justice” on a poster board and placed it on an empty coffin that he’d secured.

Fifty students joined the demonstration with the mock coffin in Tuskegee’s downtown square in front of the Confederate monument that had stood in the square since 1909, funded and placed by the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

“That was our stage, our platform,” said Paris about the Confederate monument.

After the semester ended, Paris and Younge joined SNCC activists in creating a Tent City on seven acres of land in Lowndes County. Friends of the civil rights movement purchased the land for families facing eviction from their white landowners. The evictions were a retaliatory action by landowners against people who’d participated in voter registration drives earlier in the year.

Service station attendant shoots Younge

On January 3, 1966, Paris and Younge supported an all-day voter registration drive, one of two days per month that the county permitted voter registration, registering over 100 new voters in Macon County.

Later that evening, Paris and Younge were hanging out at the Freedom House in Tuskegee with other activists.

Paris recalled putting a sticker with a Black Panther on it on Younge’s car before Younge left the Freedom House that evening.

Just before midnight, Younge drove to Tuskegee’s only all-night service station, located next to the bus depot on U.S. Route 80.

Younge got out of his car and walked over to the nighttime attendant, Marvin Segrest, 67, and asked to use the bathroom.

The two men argued and Segrest pulled out his gun and told Younge to leave, according to witnesses.

Segrest aimed his gun at Younge, and as he pulled the trigger, Younge ducked down behind his car.

Younge ran over to a nearby bus, entered and then exited. As he started to run away, Segrest shot him in the back in front of multiple witnesses, press reported at the time.

When the police arrived, officers found Younge dead on the ground, shot in the back of the head, in a pool of blood, alongside the taxi stand next to the service station.

Paris recalled learning about Younge’s death from a friend who had a two-way radio and had heard about the shooting.

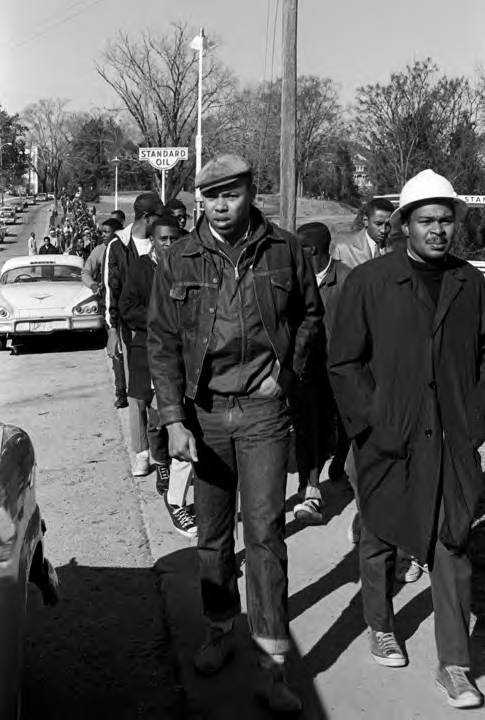

Wendell Paris leads a student protest over Samuel Younge Jr.’s killing. (Alabama Department of Archives and History/Jim Peppler/Southern Courier)

Students protest Younge’s killing

In response to Younge’s death, Tuskegee students marched the next day. Over 3,000 people turned out for the march in the rain, led by Paris and other TIAL activists. Marchers walked by the service station where Segrest shot Younge, through the downtown business district, and to City Hall, where they met Tuskegee Mayor Charles Keever and city council members on the building’s steps.

“Justice should be swiftly served,” Keever said to the students.

Keever read a prepared written statement to the crowd: “It is regrettable and tragic that this thing happened. The city of Tuskegee will do all in its power to see that every citizen gets justice regardless of race,” he said.

Younge’s father, Samuel Younge Sr., told reporters that segregationists had threatened Younge’s life for the past few months because of Younge’s involvement in advocating for civil rights.

Five Tuskegee students signed sworn statements on what they witnessed at the service station, according to press reports.

“If the federal government cannot provide protection for people seeking civil rights guaranteed by the Constitution, then people will have no protection but themselves,” said John Lewis, then-SNCC chairman, in a press release that day. “We find it increasingly difficult to ask the people of the Black Belt to remain nonviolent. We have asked the President for federal Marshals for over three years. If our plea is not answered, we have no choice.”

Funeral

The following day, on January 5, 1966, the People’s Funeral Home handled the arrangements for Younge’s funeral.

Mt. Olive Missionary Baptist Church in Tuskegee, Alabama (Liz Ryan)

Over 1,000 people attended the funeral at Mt. Olive Missionary Baptist Church in Tuskegee. Younge’s family arranged for an open casket. Reverend Sinclair T. Martin said that Younge had been “cut down as a flower,” reported media outlets.

With an American flag draped over his coffin, Younge’s family prepared for his internment at the Greenwood Cemetery in Tuskegee. Over 300 people attended, including a handful of white people.

At the funeral, Paris spoke with James Forman, who urged Paris and other activists to protest Younge’s death to federal officials in Washington, D.C., along with SNCC.

Students protest; FBI declines to investigate

The day after the funeral, Paris and four other TIAL activists drove to Atlanta and then took a flight from Atlanta to Washington D.C., funded by donations from several churches in Tuskegee, to protest Younge’s murder with federal officials.

SNCC organized a memorial service at the Lincoln Memorial, which Paris and the other TIAL activists attended. Afterwards, TIAL and SNCC activists met with the U.S. Department of Justice’s Community Relations Service and other federal agency officials.

“We will not ask the federal government to protect us anymore,” said Paris, speaking for the TIAL activists, to DOJ officials. “From now on, we will protect ourselves.”

At the same time, hundreds of students in Tuskegee continued to protest daily.

When students attempted to protest on Saturday, January 8, the sheriff stopped them.

“You do not have a parade permit. This march will not proceed,” said Sheriff Harvey Sadler to the students.

In response, the students sat down in the middle of the street. Student protests continued daily for another week.

Alabama State Troopers showed up on Sunday, January 16, 1966, in response to Sadler and Mayor Keever’s request to Governor George Wallace. Tuskegee’s Director of Public Safety also stationed police officers near groups of white men congregating on corners after receiving reports that the white men were armed, according to news reports.

Despite pleas to DOJ officials in Washington and the student protests in Tuskegee, President Lyndon Johnson’s administration declined to investigate Younge’s death.

“An extensive investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation has failed to produce evidence of a violation of a federal criminal statute,” wrote John Doar, assistant attorney general, to Tuskegee’s student body president, Gwen Patton.

Activists carry on

“We didn’t stop the voter registration when they killed him,” said Paris. “You had to keep right on going.”

In May 1966, Lucius Amerson won the Democratic primary for sheriff of Macon County over the incumbent, Sheriff Sadler. Amerson won the primary runoff by over 300 votes.

“It was a margin of what we did,” said Paris about the voter registration drives that he led after Younge’s death. Six months later, Macon County voters elected Amerson as the first Black sheriff in the Deep South since Reconstruction.

In that same election, Macon County voters elected the first two Black members of the Alabama state Legislature since Reconstruction: Fred Gray—attorney for the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—and Thomas Reed, a businessman and Macon County’s NAACP president.

Segrest’s trial, acquittal

Marvin Segrest was charged with 1st degree murder. His trial took place in Lee County rather than Macon County. Segrest’s lawyers successfully secured a change of venue, arguing that the jury pool had been tainted by all the activists protesting in Tuskegee.

“The case was lost when the motion for a change of venue was granted,” Fred Gray told reporters.

By the time the trial of Marvin Segrest took place, Paris had graduated from Tuskegee Institute and was working with the Southeast Alabama Self Help Association to support Black farmers in securing ownership of their land and accessing farming equipment and materials.

Paris attended the two-day trial at the Opelika courthouse, one of the few friends of Younge in the room, where an all-white jury sat. Segrest’s defense team successfully filed motions striking down prospective Black jurors from the jury.

Paris heard witnesses testify, including Marvin Segrest, and recalled that District Attorney Tom Young spent only five minutes cross-examining Segrest, asking very few questions.

“‘What’s your name? Do you live here? What happened?’ That’s it,” said Paris.

After the jury deliberated for just over an hour, the jury foreman issued a statement that the jury acquitted Segrest of all charges.

“We knew it was going to be a kangaroo court,” said Paris.

Impact of Samuel Younge Jr.’s death

Paris has devoted his life’s work to civil rights. Since Younge’s death, Paris has worked with Black farmers to expand land ownership, access to tools and materials, and decision-making over their lives and communities.

Historical Marker (Liz Ryan)

Paris believes that Younge was killed not because he was attempting to use a restroom at the gas station, but because of his success in registering voters.

“It was that we were registering more people than had ever registered before in Macon County,” said Paris.

Paris attributes his work with Younge as impacting the election of the first Black sheriff and the first two Black state legislators in Alabama since Reconstruction.

Their work also sparked the protest movement by Black students against the Vietnam War. A TIAL activist, Simuel Schutz, was the first Black student to resist the draft.

While SNCC is widely credited with originating the slogan “Black Power,” Paris said its origin started earlier with the work that he and Younge did in Tuskegee with TIAL.

“We ushered in the Black Power movement,” said Paris.