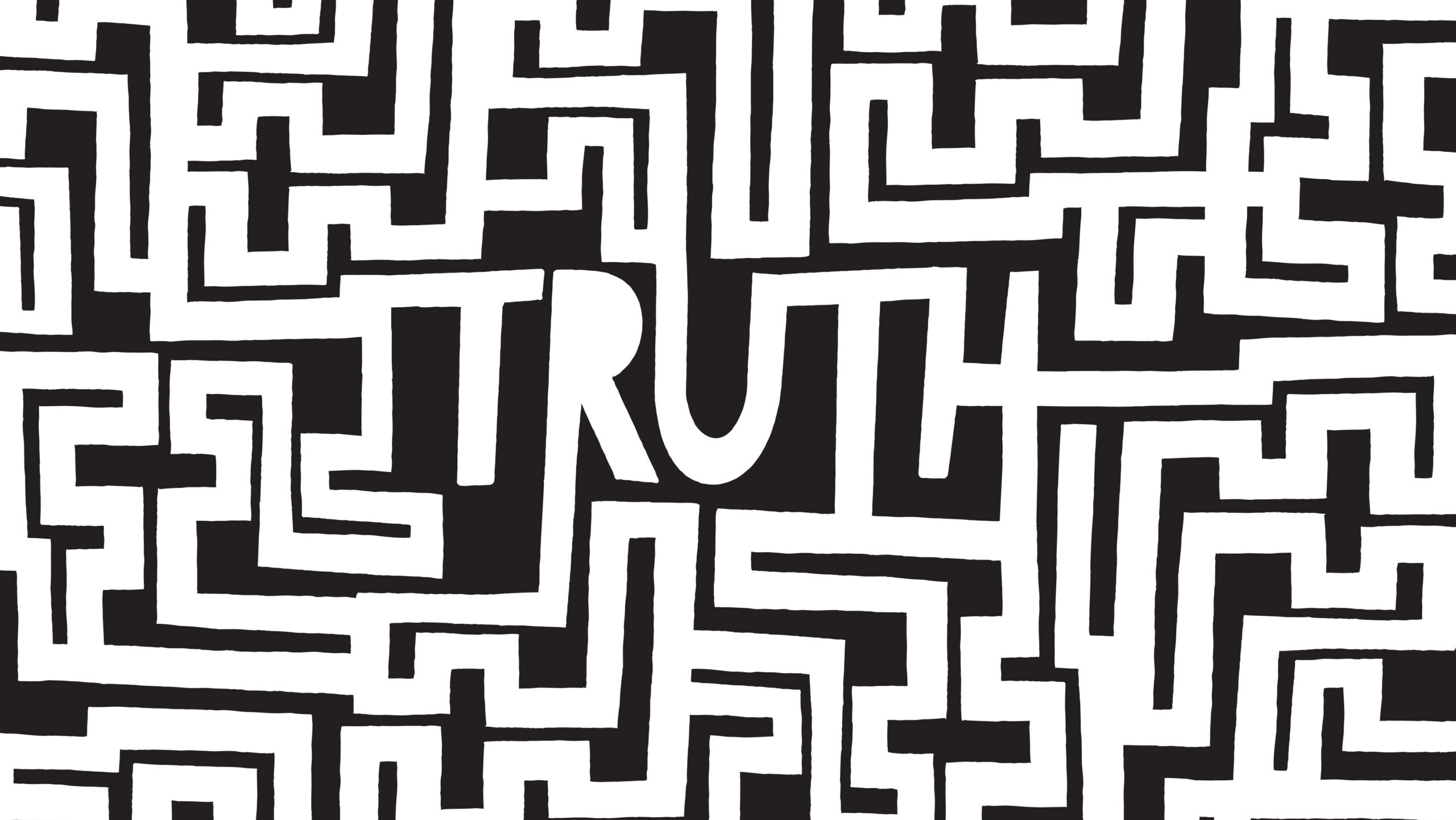

A republic cannot function when reality itself is up for negotiation. Citizens may disagree—even fiercely—about policy, priorities and power, but self-government collapses the moment facts are treated as optional and history becomes a matter of convenience. When truth loses its authority, democracy loses its footing.

That is where we are now.

This is not ordinary polarization or partisan excess. It is the steady corrosion of shared reality—a condition in which lies are no longer aberrations, but instruments, and belief becomes a test of loyalty rather than evidence. Once that line is crossed, the damage is no longer political—it becomes moral.

We watched it happen.

Police officers beaten. Windows shattered. Lawmakers fleeing for their lives. The United States Capitol breached in broad daylight. Not in secret. Not in the shadows. On live television, streamed to millions of screens across the country.

And then, almost immediately, we were told it didn’t happen—or that it happened differently than we remembered. That what we saw with our own eyes was exaggerated, staged, misunderstood or somehow patriotic. The lie did not wait for time to dull memory. It arrived while the footage was still fresh, while the smoke still lingered—one of many examples we see today of how lies, when repeated and rewarded, replace reality, particularly when those in power profit from spreading them.

That moment marked something deeper than a political fracture. It signaled something far more dangerous: the breakdown of reality itself.

John Adams warned that facts are stubborn things. He understood that a republic does not require unanimity, but it does require reality. When facts become negotiable, accountability collapses by design. When history becomes optional, power becomes unmoored.

The harder question—and the one we must confront honestly—is this: why are so many willing to spread lies, and why are so many eager to believe them?

Part of the answer is uncomfortable. It has less to do with ignorance than with human need.

For many, lies offer something truth does not: comfort. Reality is complicated. It demands adaptation, humility, and sometimes reckoning with the painful truth that promises made were never kept, that sacrifices did not lead where expected, that the world has changed in ways no one fully controls. Truth asks people to live with ambiguity and responsibility.

Lies simplify. They offer villains instead of complexity, certainty instead of nuance, belonging instead of doubt. They tell people they are not wrong or left behind, but robbed. And once a lie begins to explain why someone feels diminished, it stops being a falsehood and becomes shelter.

That explains belief. But it does not explain power.

Those who knowingly propagate falsehoods are rarely confused. They are strategic. Truth constrains power. It creates records, standards and consequences. Lies dissolve those limits. When nothing is stable, the loudest voice wins. When everything is disputed, nothing can be judged.

This is why attacks on journalists, historians, educators and civil servants always accompany the rise of authoritarian politics. These institutions do not dictate belief; they anchor reality. Remove the anchors, and power floats free.

There is another truth that must be named, even if it makes people uncomfortable.

I have watched politicians I have known personally bend themselves into lies they knew were lies. I have seen men and women who understood the consequences of their votes cast them anyway—not because they believed the policy was right, but because it was expedient. Because it protected their position. Because it advanced their careers. Because it kept them in the game.

This raises an unsettling question: did their conscience change—or were they always capable of this?

In many cases, the answer is neither. What we are witnessing is political self-preservation allowed to metastasize—the slow trade of principle for proximity to power, and the illusion that the trade is temporary. The quiet decision, made once and then repeated, that survival matters more than truth.

Most do not begin by telling themselves they are doing harm. They tell themselves they are being pragmatic. That this is one bad vote to preserve influence. One lie to prevent a worse outcome. One compromise to live and fight another day. They tell themselves that once they secure power, they will use it for good.

But conscience does not work that way.

What begins as exception becomes habit. What is justified once becomes easier the second time. And eventually, the distinction between necessity and convenience disappears altogether. At that point, it no longer matters whether someone believes the lie—only that they are willing to repeat it.

We often say that evil prevails when good people do nothing. But what are we to make of those who do not merely stand aside, but actively enable falsehood? Who lend their credibility, their votes and their silence to things they know are wrong—not out of conviction, but calculation?

This is not moral neutrality. It is moral abdication.

And when abdication becomes routine, it reshapes character. The lie stops feeling like a lie. The vote stops feeling like a betrayal. The harm becomes abstract. At some point, the question is no longer whether someone is doing bad things for good reasons, but whether they have become the kind of person for whom the reasons no longer matter at all.

History is unsparing on this point. Systems of injustice are rarely sustained by villains alone. They depend on people who know better—people who convince themselves that their participation is temporary, necessary or harmless. It is not.

Character is not revealed only in moments of courage. It is formed in moments of rationalization.

This moral collapse does not stop with individuals. It spreads outward, into institutions and memory itself. We see it in efforts to sanitize slavery, soften segregation, and recast the Civil Rights Movement as excess rather than necessity. History is not being debated; it is being bleached. The goal is not understanding, but absolution.

A society can survive fierce disagreement. It cannot survive when large segments of the population inhabit incompatible realities. Law becomes arbitrary. Elections lose legitimacy. Violence becomes justifiable. Cynicism replaces citizenship.

There is no quick fix for this. No single election or lawsuit will restore a shared sense of reality. The road back is longer and harder. It requires rebuilding trust in institutions that can be corrected but not destroyed. Teaching history honestly—not to shame, but to understand. Restoring civic literacy so citizens know not only what they believe, but why.

Most of all, it requires moral courage.

The courage to say what happened, happened. The courage to insist that facts matter. The courage to live with truth even when it costs comfort, tribe or applause.

A free people can argue passionately about policy, priorities and power. That is democracy at work. But a free people cannot survive without reality. A republic does not fall when it disagrees. It falls when too many decide that truth no longer matters.

And once truth becomes optional, freedom is never far behind.