State Auditor Andrew Sorrell has spent the last several years selling Alabamians a brand: fiscal discipline, moral clarity and the promise of clean government.

But when APR examined the public record of his political and financial activity in July 2025, what emerged was not a single mistake or a harmless paperwork error. It was a pattern that sits squarely in the gray space Alabama politics has long tolerated. Not hidden. Not subtle. But corrosive, because it depends on loopholes, delayed disclosures, and a system that reveals just enough to satisfy the law while concealing far more from voters.

At the center of the story are three things: Stable Revolution LLC, the Alabama Christian Citizens PAC and Sorrell himself.

And then, quietly, after reporters began connecting the dots, the company disappeared.

You can call that legal. You can call it careless. Sorrell has called parts of it a “tough lesson.”

But it is not what ethical government should look like.

A company that appeared at exactly the right moment

According to Alabama Secretary of State business records, Stable Revolution LLC was formed on January 12, 2024. The registered agent is listed as “Sorrell, Justin A.” at a Muscle Shoals address—an identity APR confirmed refers to Andrew Sorrell.

Within weeks, campaign finance reports show that Allen Long’s campaign for the State Board of Education began paying the company substantial sums.

Those filings list: $207,050 in payments categorized as “advertising,” $17,615 labeled as “consulting” and a post-election $12,000 transaction described as a “refund.”

Together, the payments totaled $236,661.59 routed through Stable Revolution in just a few months.

Sorrell told APR he was helping a longtime friend, said he did not take a percentage of advertising placements and described his personal compensation as a one-time “win bonus.”

Those explanations may be accurate.

But the amount of money routed through a company tied to a sitting statewide official is extraordinary for a down-ballot education race—an office that historically draws modest fundraising and little public attention.

Even when something is legal, scale matters.

A structure that invites abuse

The same public records show that a significant portion of Long’s early campaign funding came from the Alabama Christian Citizens PAC, which Sorrell chairs and controls.

At roughly the same time, Long’s campaign was paying Stable Revolution.

So the structure looked like this: Sorrell chaired the PAC. The PAC funded Long. Long paid a company registered to Sorrell.

No statute explicitly forbids this arrangement. But laws are meant to prevent conflicts of interest, not merely catalog them.

Even if every dollar was spent exactly as Sorrell says, the design places a public official in the middle of political fundraising, campaign spending and private business income.

That is not a technical problem. It is a structural one.

A disclosure that changed after questions were asked

When APR reviewed Sorrell’s Statement of Economic Interests, Stable Revolution was not listed.

Only after questions from APR’s Josh Moon did Sorrell amend the filing. The revised disclosure added Stable Revolution and several other businesses, representing tens of thousands of dollars in previously undisclosed income ranges.

Sorrell said the omission was a mistake.

Perhaps it was.

But it is also true that voters learned about a substantial financial interest only after journalists asked why it was missing.

That matters—especially because Sorrell briefly ran for secretary of state, the office that oversees campaign finance reporting and ethics disclosures.

He later withdrew from that race.

He is now running again for state auditor, the same office he held while these disclosures were incomplete.

The Georgia investment that became something else

Campaign finance filings also show that the PAC chaired by Sorrell loaned $29,000 to First Liberty Building & Loan, a Georgia firm now accused by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission of operating a $140 million Ponzi scheme.

The PAC later reported receiving interest payments.

Sorrell has said the PAC believed it was making a legitimate investment and that he personally lost money as well.

There is no public evidence he knew the firm was fraudulent at the time.

But political action committees exist to influence elections—not to function as lenders or speculative investment vehicles. Sending political money to a private out-of-state lender that later collapses into a federal fraud case is, at minimum, a profound lapse in judgment for a statewide financial watchdog.

The quiet end of the company

Secretary of State records show Stable Revolution LLC was dissolved on December 9, 2025.

There was no public explanation. No accounting. No announcement.

The company that had taken more than $236,000 from a single campaign and had been omitted from an ethics filing simply ceased to exist on paper.

That may be routine business procedure.

It is also convenient.

Now he wants another term

Andrew Sorrell is no longer running for secretary of state.

Instead, he is asking voters to return him to office as state auditor—the official tasked with guarding financial integrity in government.

He is not asking to be trusted with a new responsibility.

He is asking to be trusted again.

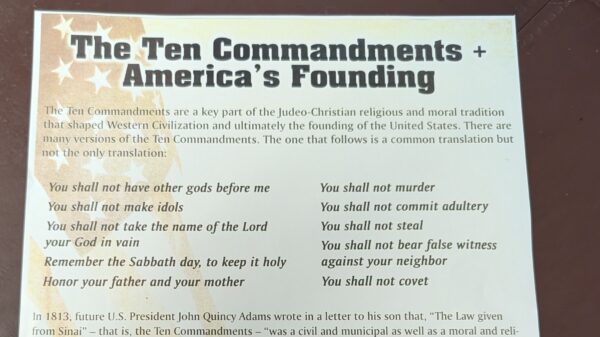

What Alabama is really being asked to accept

Defenders will say none of this violates the letter of Alabama law.

They may be right.

But law is the floor, not the ceiling.

Should public officials be allowed to own private consulting firms that are paid by political campaigns they help finance?

Should political action committees be allowed to function like shadow banks, lending campaign money to private, out-of-state companies?

Should candidates be allowed to omit businesses from mandatory ethics filings, correct the record only after reporters notice, and hide the true scope of their income behind disclosure ranges so broad they inform no one?

These are not technical questions.

They are moral ones.

And they go to the heart of whether Alabama wants elections governed by trust—or by clever compliance.

Andrew Sorrell did not invent this system.

But he has shown that he understands how to operate inside it.

The question for voters is whether that is what they want rewarded with another four-year contract.

Because public office is supposed to be a duty.

Not a business plan.