Long before Alabama voters cast a single ballot, the legality of the next governor’s election may already be in question.

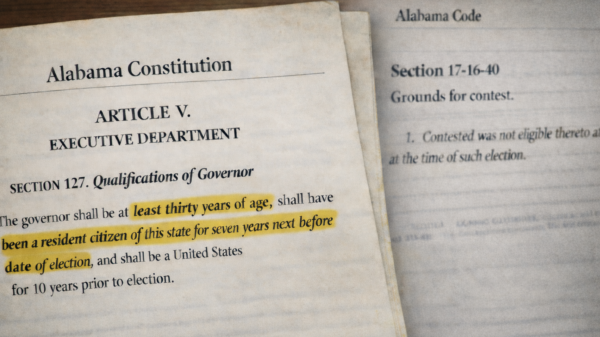

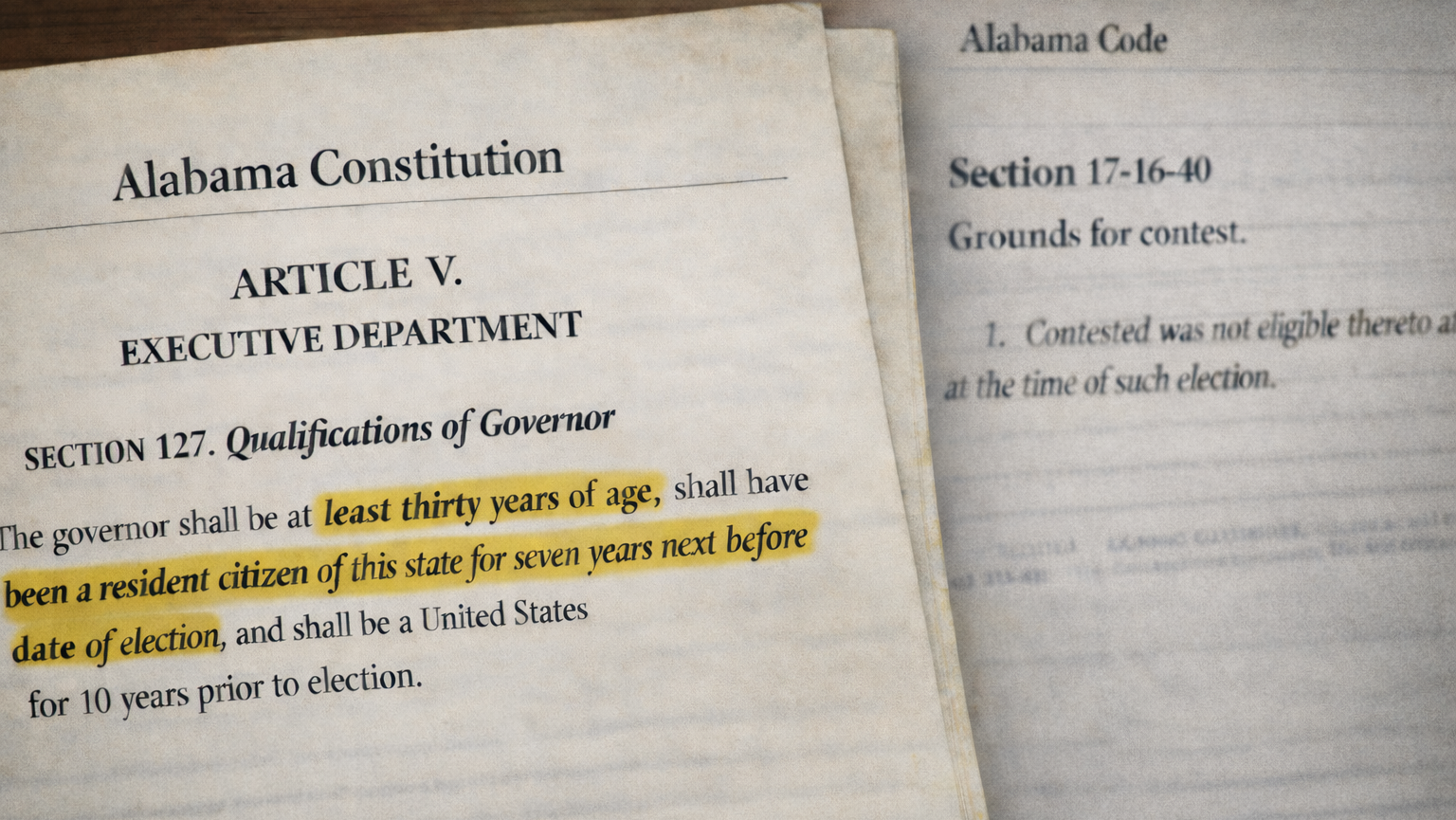

Since U.S. Senator Tommy Tuberville announced his intention to leave the Senate and seek the governorship, attention has fixed on a constitutional requirement that does not bend to campaign messaging or real-estate paperwork: a governor must have been a “resident citizen of Alabama at least seven years next before the date of their election.”

Tuberville maintains that he satisfies that requirement, pointing to a home in Auburn as his primary residence rather than his long-time property in Santa Rosa Beach, Florida. Whether that claim would withstand formal scrutiny remains an open legal question. What is not uncertain is how a challenge would proceed if he were to win.

Under Alabama’s election-contest statutes, the decisive post-election fight would not be tried in court. It would be tried in the Legislature.

That distinction matters, because the Legislature is not a neutral tribunal. It is a political body.

Two challenges, two different systems

A residency challenge could arise in two phases.

The first would occur during the Republican primary. Political parties in Alabama retain broad authority to determine whether a candidate may appear on their primary ballot. Any such challenge would be initiated and resolved under party rules through internal party processes. Courts have historically been reluctant to substitute their judgment for party decisions on candidate qualifications, particularly where those decisions rest on party rules and associational rights. In practice, challenges of this type are rarely successful when directed at major candidates.

The second challenge would occur only after the general election, if Tuberville were certified as the winner. At that point, the process becomes a formal election contest governed entirely by state law.

When and how a gubernatorial election may be contested

Alabama law expressly allows a gubernatorial election to be challenged when the winning candidate was constitutionally ineligible.

Alabama Code §17-16-40 provides that an election may be contested when “the person whose election to office is contested was not eligible thereto at the time of such election.”

Residency, therefore, is not a technical formality but a constitutional qualification. A candidate who does not meet it for the required seven years preceding the election is legally ineligible to hold the office, regardless of the vote total.

Who decides the contest

Alabama does not assign gubernatorial election contests to the judiciary.

Under Alabama Code §17-16-65, contests for the office of governor are tried by the Alabama Legislature sitting in joint convention.

The statute states that the House and Senate “shall constitute the tribunal for the trial of all contests for the office of Governor” and that their final judgment “shall have the force and effect of vesting the title to the office.”

The Speaker of the House presides. Evidence is presented. Arguments are heard. A simple majority of the combined membership decides all questions of fact and law.

In practical terms, the Legislature functions as both trial court and jury.

Why courts play almost no role

Alabama law sharply limits judicial involvement in election contests.

Alabama Code §17-16-44 states that “no jurisdiction exists in or shall be exercised by any judge or court to entertain any proceeding for ascertaining the legality, conduct, or results of any election,” except where specifically authorized by statute. The law further declares that any court order attempting to interfere with certification or election results is null and void.

In practical terms, this means a circuit court cannot block certification, disqualify a candidate or decide residency eligibility in a post-election contest. The Legislature alone exercises that authority.

Courts may still be asked to consider narrow collateral or constitutional questions in extraordinary circumstances, but they do not conduct the contest itself and do not determine eligibility in the first instance.

What happens if the winner is disqualified

Disqualifying a winning candidate does not elevate the runner-up.

Alabama courts have long held that when the candidate receiving the most votes is ineligible, the election fails and the office is treated as vacant.

That rule was established in State ex rel. Stacy v. Stearns (1955) and reaffirmed in Banks v. Zippert (1985). In those cases, the courts made clear that votes cast for an ineligible candidate do not transfer to the second-place finisher, because that candidate was rejected by the electorate.

For a gubernatorial race, the consequences are unusually stark.

If Tuberville were elected and later ruled constitutionally ineligible by the Legislature, the office of governor would be deemed vacant, and succession would occur under Alabama’s constitutional vacancy provisions, under which the lieutenant governor would assume the office.

The voters’ second choice would be legally irrelevant.

The political reality beneath the law

This system produces an uncomfortable truth.

A residency challenge would not be resolved by neutral judges weighing property records and tax filings. It would be decided by elected lawmakers, many of whom would share political affiliations, donors and institutional interests with the candidate whose eligibility they are judging.

The process is legal. It is constitutional. It is long-standing.

But it is also unavoidably political.

The risk Tuberville is accepting

Modern campaigns often operate on the assumption that winning cures every defect.

Alabama law does not share that assumption.

Votes do not override constitutional qualifications. Certification does not erase eligibility requirements. Popularity does not create legal residence.

If Tommy Tuberville wins the governorship and his residency is challenged, the question will not be whether he prevailed at the ballot box.

It will be whether he was ever legally qualified to appear on it.

And under Alabama law, that decision would rest not with a judge, not with the voters and not with any neutral body of referees — but with the Legislature itself.

That is the system Alabama has chosen.

And it is the system every candidate, including Tommy Tuberville, accepts the moment they ask to govern.