By Lee Hedgepeth

Alabama Political Reporter

BESSEMER – For the first time since his company was named in multiple court documents related to the Lee County public corruption investigation, American Pharmaceutical Cooperative, Inc. CEO Tim Hamrick has spoken out, shining light on some of the earlier events that led to the eventual arrest and conviction of then House Representative Greg Wren, R-Montgomery, on charges of using his office for public gain and misleading investigators.

Last week, Hamrick sat down with veteran Associated Press reporter Phillip Rawls, and what he said was almost as revealing as what he didn’t say.

What he did not say, and what is ultimately (at least part) of the purpose of the Lee County public corruption investigation, is the extent of Speaker Mike Hubbard’s involvement in the addition of language into the 2013 General Fund budget that would have, had the Governor not rejected it, given a complete monopoly over certain Medicaid prescription plans to the company.

Instead, on the topic of the Speaker, Hamrick “declined to discuss Hubbard’s work for APCI because of the investigation and would not say whether he or anyone with the cooperative has been subpoenaed to testify to the grand jury.”

Hubbard has confirmed, though, that he did have a consulting contract with APCI for an undisclosed amount until late last year.

APCI/CEO Hamrick did, though, elaborate on other facets of the equation, including APCI’s relationship with RxAlly, with Representative Wren, and with the State’s Medicaid agency.

In 2013, the State’s Medicaid agency, led by director Don Williamson, began studying the idea of maximizing cost saving by switching to a pharmacy benefit manager, or PBM, a move which internal cost-benefit analysis demonstrated might create fiscal promise.

That move toward studying PBMs, though, spooked APCI, whose individual pharmacy members stood to lose profits from dispensing fees if a large benefits manager came into Alabama. As a result, the group sought to work with the Medicaid agency to develop a plan to limit costs without the use of a PBM. According to Mr. Hamrick, though, that never really happened.

“[Hamrick] said he tried – unsuccessfully – to work with state Health Officer Don Williamson, who oversees Medicaid, to give APCI a chance to develop a plan that would save money while maintaining the dispensing fee,” the AP article explains.

Given his defeat in working with Williamson, Hamrick said that the group switched their focus to the legislative branch, a move that would later turn to haunt some on Goat Hill.

“We were concerned that Medicaid was not hearing our concerns that what was being offered sounds really good, but it’s just not sustainable,” Hamrick told AP, “so that is when we started turning to the Legislature.”

And turn to the Alabama Legislature they did.

In the AP interview, Hamrick was deliberate in distancing APCI from RxAlly, saying that “APCI only owned 2 percent of RxAlly, the company that paid Wren,” despite all approximately 1,300 APCI pharmacies holding an RxAlly membership until the latter group dissipated.

Though he may not be proud of the connection now, APCI certainly was when the partnership began in February 2012. A press release from the occasion read:

“APCI announced the participation of its 1,200 independent member pharmacies in RxAlly, the first-of-its-kind alliance of more than 20,000 pharmacies nationwide, united to help patients achieve better health through personalized pharmacist care while reducing costs.”

And, despite the alleged chasm between the companies, Hamrick apparently had knowledge of RxAlly’s payroll decisions, telling AP that Wren was hired by the group because of his background in the insurance business.

“What happened from there I have no idea,” Hamrick said.

Though there is no evidence, Hamrick’s selective memory about “what happened from there” might have to do with the events described in detail in Rep. Greg Wren’s plea deal, to which the former Representative agreed under penalty of perjury and the revocation of a year suspended jail sentence. The deal, which included a narrative “statement of facts,” said that Wren, after instructions from RxAlly staff, obtained copy of the very PBM cost analysis that Hamrick had wanted, and illegally provided it to APCI’s affiliate via mail.

This information was, in all likelihood, used to construct the language inserted into the 2013 General Fund budget that are at the center of this investigation. The 23 words, which never mention the company by name, provided specific numerical criteria to be met for companies to bid for the contract – criteria which only APCI met.

Don Williamson has confirmed several times that he was aware that the language would have provided a monopoly to APCI, and that he fought to have the language removed, statements that fit in with Hamrick’s claims that the Medicaid agency and APCI were not on the best terms.

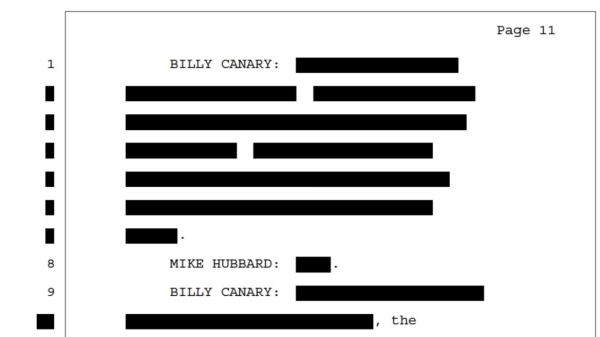

Wren’s plea deal also asserted that Speaker Hubbard not only had legislative staff draft the language, but also that he had “endorsed” the wording himself, a claim the Speaker denies.

Hubbard does say that he realized before he voted for the budget that the Medicaid language benefited only APCI, a company from which he received pay.

“When the language is put in, I find out when I’m walking in the chamber to vote on the budget that the way it was written that the only entity in the state able to do it is APCI,” Hubbard told Opelika-Auburn News earlier this month.

Hubbard went on to vote for that version of the budget in the affirmative not just once, but a total of a dozen times.

Hamrick says that APCI and RxAlly turned to the Alabama Legislature. They did. When they got there, it seems that Speaker Hubbard and Representative Wren opened not just the doors to their office, but the doors to the State treasury.

Speaker Hubbard was officially revealed to be the prime subject of the Lee County public corruption inquest in a letter by Attorney General Luther Strange authorizing supernumerary St. Clair County District Attorney W. Van Davis to investigate the case earlier this month. Until then, Hubbard had denied he was involved.

No action has been taken by the grand jury since the indictment of State Representative Barry Moore, R-Enterprise, on charges of felony perjury at the beginning of June. Having lost a motion to dismiss the charges, Moore’s trial is scheduled for September.