Almost half of Alabamians experienced a loss in income since the COVID-19 crisis began, and more than 13 percent said they hadn’t had enough to eat during the prior week, according to a recent survey, but there is help for families with children struggling with food insecurity.

Two federal programs combined can help keep Alabamians fed during coronavirus’s continued impact on health and finances, but there’s work to be done to ensure those programs are fully used, and will continue to help during this time of need, according to Alabama Arise, a nonprofit coalition of advocates focused on poverty.

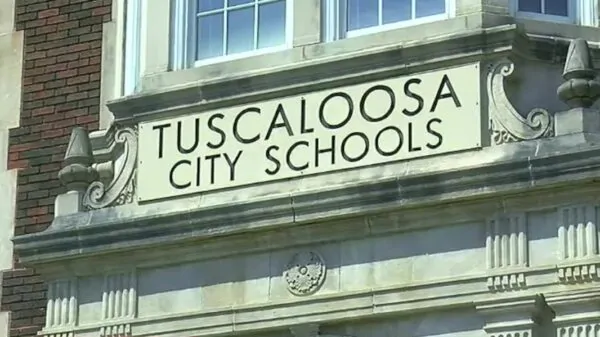

Celida Soto Garcia, Alabama Arise’s hunger advocacy coordinator, on Friday discussed the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), which allows schools with high poverty rates to serve breakfast and lunch to all students, regardless of a parent’s income.

There are still a little more than 100 school systems in Alabama that would qualify under the program, but haven’t yet applied to do so, Garcia said.

“Schools that had implemented CEP prior to the pandemic made it a lot easier to distribute food. They didn’t have to worry about eligibility and delayed distribution,” Garcia said.

Garcia said the coronavirus crisis has brought attention to the CEP program and that some school board officials and child nutrition professionals are beginning to identify which school systems could qualify for the aid.

“So that of course was a benefit prior to the pandemic, and now there’s just an increased need for it,” Garcia said.

Carol Gundlach, a policy analyst at Alabama Arise, discussed with APR on Friday the pandemic Electronic Benefit program (P-EBT), which gives parents of children who receive free and reduced lunches a debit card loaded with value of each child’s school meals from March 18 to May 31. The cards can be used at any grocery store.

Immigrant families with children enrolled in school can also receive the P-EBT cards, Gundlach said.

“We of course hope that Congress will see their way to continuing pandemic EBT for the remainder of this summer, because of course, children still have to eat, whether school is in or not, and families are still going to have to pay for those extra meals,” Gunlach said.

Just more than 13 percent of Alabamians polled said they didn’t have enough to eat during the week prior, according to a survey by the U.S. Census Bureau, and 43 percent said they’d experienced a loss of income due to the COVID-19 crisis.

“So clearly parents are going to have a very difficult time continuing to feed the whole family through the summer,” Gundlach said. “It’s really a serious crisis and continuing Pandemic EBT would make a really big difference.”

Many individual school systems across the state are working hard to supply sack lunches to students in need, but without federal aid it will be hard to keep those meals coming all summer, Gundlach said.

There was an expansion of P-EBT for the remainder of the summer, and a 15 percent increase in regular Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, known as food stamps, in the $3 trillion Heroes ACT, which Democrats in the U.S. House passed last week. Gundlach said she hopes the U.S. senators from Alabama get behind the Heroes Act.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Kentuky, said last week, however, that if the Senate takes up another round of coronavirus relief legislation it won’t look like the House version, according to NBC News.

Gundlach also wanted those without children to know that there’s additional food assistance available to them.

The Family’s First Act temporarily suspended SNAP’s three-month time limit on benefits, and Gundlach said that even if a person was denied assistance before because they hit that time limit, they can reapply and receive that aid.