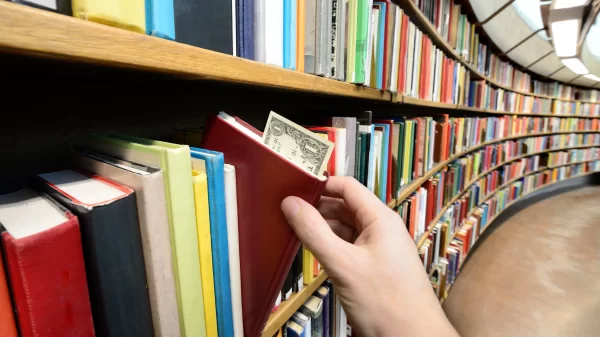

After writing a story last week about a federal judge striking down a Florida law that would allow for school libraries to remove books containing “sexual conduct,” I wondered whether I should write an opinion further explaining how it correlates to Alabama’s situation or whether that might be too repetitive.

But then I saw an opinion written by Autauga-Prattville Public Library attorney Laura Clark on the far-right media site 1819 News rebutting my article and clearly misunderstanding or misrepresenting it. It made me think, if this attorney who emphasizes her expertise in Constitutional law could be so far off the mark, surely I need to explain it again for the layperson.

The most significant finding in the ruling issued by U.S. District Judge Carlos Mendoza, in my opinion, is that the extent of the government’s ability to restrict speech as obscenity for minors depends on the Miller-for-minors test.

The Miller-for-minors test is an offshoot of “The Miller Test” for obscenity established by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1973 that lays out three prongs for the consideration of whether material is obscene. The Miller-for-minors test comes from Ginsberg v. New York and gives an altered version of that test to account for differences in what is obscene between minors and adults.

This Miller-for-minors test serves as the basis for both Florida and Alabama definitions of “material harmful to minors” already enshrined in law. It is the very law State Representative Arnold Mooney, R-Indian Springs, has been attempting to change for the past three years in increasingly complex and nonsensical ways to effectively keep books promoting more than two genders away from minors in libraries.

Any books about transgender people for children removed from minor sections under Mooney’s law—if it were to ever pass—would be ripe for a lawsuit if nothing else due to the first prong of the Miller-for-minors test, which states that a book is obscene as to minors if, when taken as a whole, it appeals to the prurient interest of minors (which has been defined as a morbid interest in sexuality). Very few, if any, of the books challenged in Alabama libraries containing representations of transgender stories discuss sex at all. The state would be hard-pressed to argue that any book removed under the statute, especially when viewed holistically, would appeal to a morbid interest in sexuality.

The Alabama Public Library Service code also likely runs afoul of the argument in this ruling, although APLS has a distinct layer, as they are not outright forcing libraries to remove or move books but instead conditioning funding on moving books. That would likely run afoul of the “unconstitutional conditions doctrine” if the mandate itself were found unconstitutional.

The mandate itself aligns closely with the Florida law allowing schools to remove books for “sexual conduct” outside of the scope of the state’s “harmful to minors” statute–which it bears recalling is almost identical to the Miller-for-minors test.

As far as Mendoza is concerned, Florida’s law is patently unconstitutional.

“Here, neither a prohibition on content that ‘describes sexual conduct’ nor that which is allegedly ‘pornographic’ takes the third Miller prong into account,” Mendoza wrote. “Both prohibitions lack the specificity required in identifying obscene material. Given that obscene material as to minors is already prohibited under Florida law, these terms must, therefore, target non-obscene material. Thus, the applications of the law plainly slip into those barred by the First Amendment.”

Mendoza made it clear that the only blanket prohibition the government can place on library materials for minors is that which aligns with the Miller-for-minors test. But the APLS code goes far outside that scope by ignoring the requirement that the material be looked at as a whole, whether it has literary, scientific, artistic or political value for minors, or even whether it is patently offensive for minors. It takes an overbroad approach to denying all descriptions of sexual intercourse, no matter the context, no matter how brief. APLS Chairman John Wahl has tried to rely on the flimsy definition of “sexually explicit” by pointing to a federal statute regarding child pornography, but that does nothing to address the clear First Amendment hurdles the provision faces.

Mendoza actually goes so far as to call the state of Florida’s argument “bewildering” in that the law not only fails under strict scrutiny, the highest bar for the government to clear, but fails even lower standards.

“Defendant’s final salvo bewilderingly argues that Plaintiffs have failed to show that the statute would not survive strict scrutiny. But Plaintiffs established it would not survive an even weaker form of scrutiny. To put it another way, if the statute cannot clear a three-foot hurdle, there is no need to demonstrate whether it can clear a six-foot hurdle. Strict scrutiny is the least favorable standard of review for the government. To make this argument even more baffling, the burden there is on the government … Therefore, it is readily apparent to the Court that the statute fails strict scrutiny. The statute’s prohibition of material that “describes sexual conduct” is overbroad and unconstitutional.”

Clark’s opinion bizarrely misses explicit references to the Miller-for-Minors standard in both my article and Mendoza’s ruling, which references the concept six times in a multi-page exploration of how it applies to the Florida case. Yet Clark claims that the concept is “something Mendoza and APR have skipped over entirely.”

It is distressing that a lawyer representing one of our libraries either did not read the ruling or completely misunderstood it, and it is even more disturbing that legal theory so similar to Clark’s is serving as the basis for Alabama and Florida’s blatantly unconstitutional censorship.