Welcome to Alabama, where regressing 12 years is actually progress.

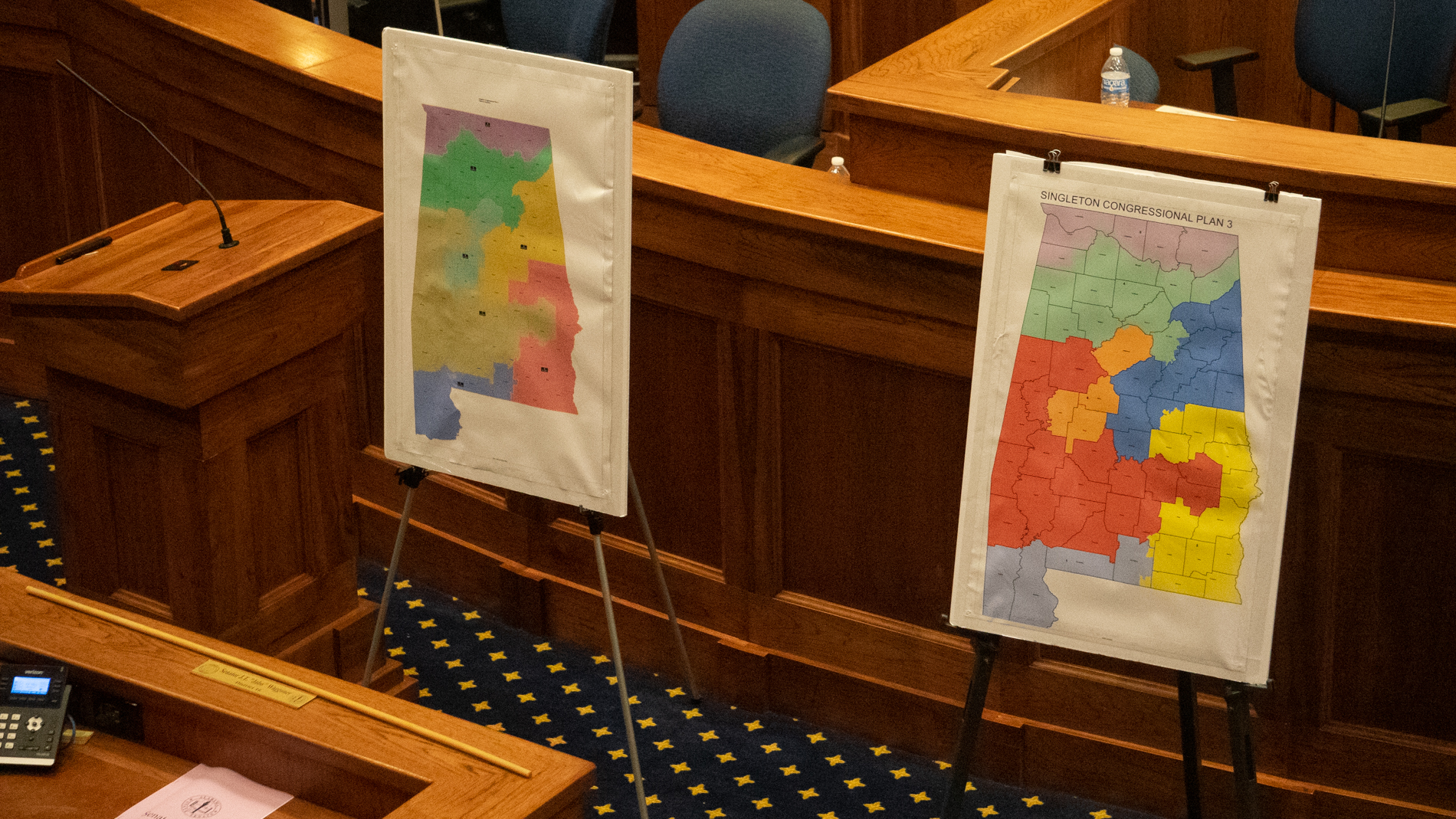

On Thursday, a federal three-judge panel ruled that state lawmakers here had been so unapologetically racist in drawing their congressional voting maps – and then so cavalierly defiant when told to correct their racism – that the court could see no way that it couldn’t be exactly what it appeared to be: Blatant racism.

That, of course, is no surprise.

The federal court ruled back in 2022 that Alabama’s maps were improper and infringed upon Black voters’ rights to equal voting power. State Republicans accomplished this by dividing the state’s voting districts in such a way that Black voters were packed in a handful of districts, making it impossible for them to achieve appropriate representation.

The math didn’t lie. Despite the state having a Black population of more than 25 percent, less than 15 percent of its congressional districts contained enough Black voters to meaningfully affect an election’s outcome.

The Supreme Court, surprisingly, agreed with the lower courts and ordered Alabama lawmakers to redraw their maps and provide for at least two districts in which Black voters had the opportunity to elect a candidate of their choosing.

Republicans scoffed. Then whined. Then chose defiance in the hope that the Supreme Court would, at some point in the future, take up their cause and do away with the Voting Rights Act completely.

And maybe it will — that particular incarnation of the Highest Court has proven it cares nothing about precedent and decency — but if it does so now, it will have to act in the face of a state Legislature — one with a supermajority — behaving in such a blatantly racist manner than it now faces being thrust back under preclearance requirements.

That was the determination of the three-judge panel last week: That Alabama Republicans had behaved so discriminatorily by drawing maps that not only defied their orders but were worse than the original maps that the court would now consider placing the state back under preclearance. That would require Alabama lawmakers to seek court approval before any significant changes were made to voting laws in the state.

Alabama, because of its very, very racist past, was under preclearance for much of the last 60 years – from 1965 until the egregious 2013 Shelby v. Holder decision by the Supreme Court struck down Section 5 of the VRA.

The state celebrated being removed from preclearance by immediately changing a slew of voting laws that made it more difficult for Black voters to cast ballots. But what most people failed to realize, while appropriately weeping for the loss of Section 5 protections, is that preclearance can still be applied by federal courts in response to egregious acts by states and other jurisdictions.

Like, for example, if a state legislature received an order from a federal court to draw a second minority district and instead drew maps that were even more racist.

It’s worth noting here that this particular three-judge panel isn’t exactly a panel of bleeding heart libs, either. It’s constructed of two judges appointed by Donald Trump and another appointed by Bill Clinton (but who was originally nominated to the federal bench by Ronald Reagan). It is generally viewed as one of the more conservative courts in America.

That court wrote this: “try as we might, we cannot understand the 2023 Plan as anything other than an intentional effort to dilute Black Alabamians’ voting strength and evade the unambiguous requirements of court orders standing in the way.”

It’s worth reminding you, I think, that Alabama Republicans did this while governing a state in which no Black person holds elected statewide office. Only one Black person sits on the state appeals courts. No Black person sits on the Alabama Supreme Court.

It also comes during a time when Alabama Republicans have relentlessly attacked diversity, equality and inclusion efforts around the state, have sought to ban the teaching of history lessons that accurately reflect the country’s and the state’s history of racism and discrimination and have sought to protect various confederate symbols and statues.

All of it summed up by this pathetic, yet telling, reality: Should Alabama be placed once again by this federal court under preclearance requirements, it would be like returning the state to 2012.

And somehow, going backwards a dozen years would be tremendous racial progress.