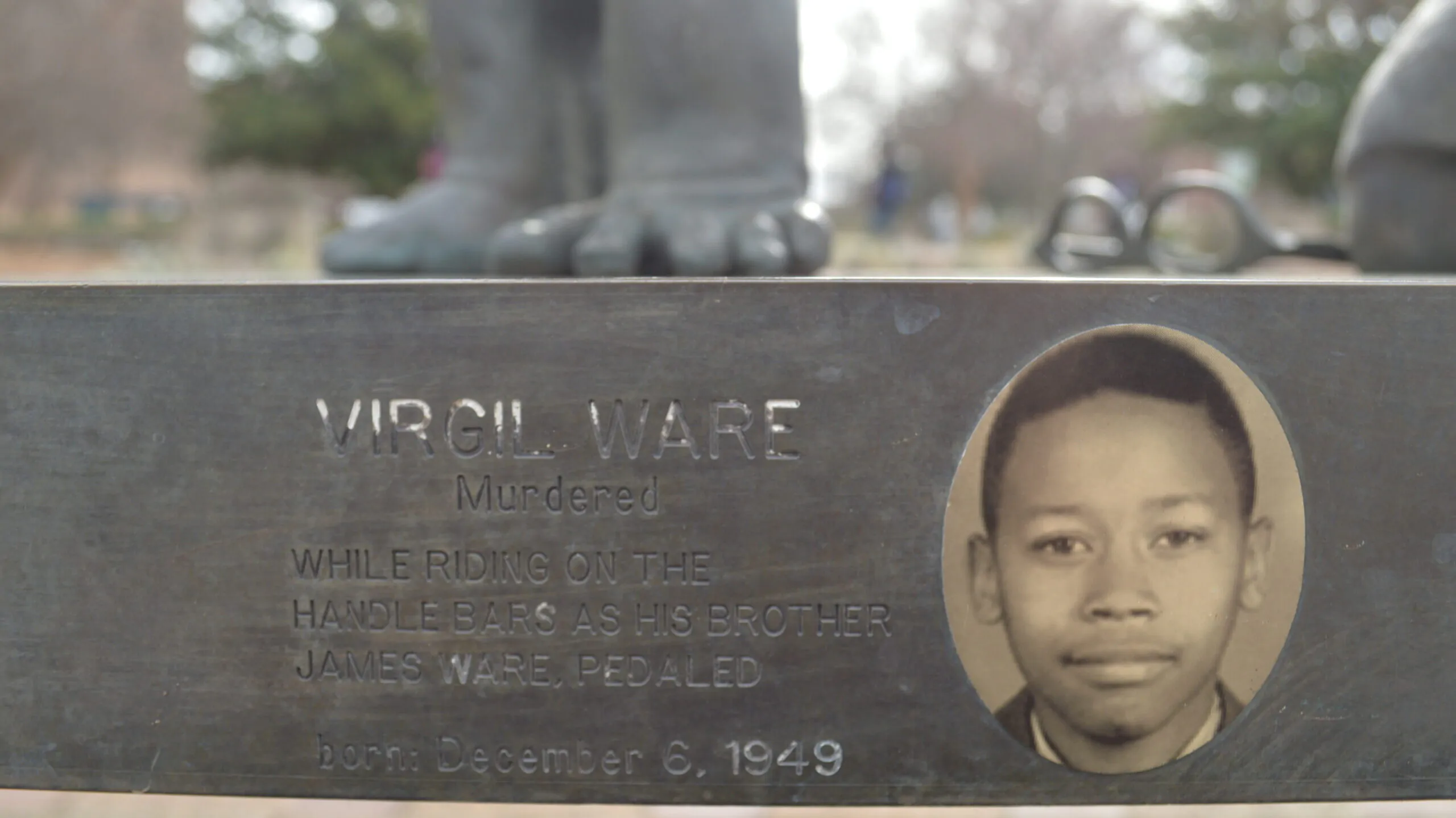

“I can’t get up, I’m shot,” cried 13-year-old Virgil Ware.

Lying on the ground with bullet wounds in his chest and face, Virgil Ware went silent.

He died before the ambulance arrived to take him to a Birmingham hospital.

It was September 15, 1963, hours after a bomb exploded at the 16th Street Baptist church, killing four Black girls: Addie Mae Collins, 14; Denise McNair, 14; Carole Robertson, 14; and Cynthia Wesley, 11.

In the aftermath of the bombing, violence reigned across the city and into the evening.

A brief mention in local newspapers the next day noted Virgil Ware’s murder, along with another Black teen, Johnnie Robinson, 16, who was shot in the back by a Birmingham police officer.

“Almost lost in the press coverage and national outpouring of grief and recrimination, the two young boys killed that same Sunday became forgotten footnotes to the central tragedy of September 15, 1963,” says author and emeritus professor Randall Jimerson in his book Shattered Glass in Birmingham.

Arrested by Birmingham police detectives on a lead from a chance encounter with an anonymous tipster, Larry Joe Sims, 16, and Michael Farley, 16, admitted to police that they’d shot and killed Virgil Ware.

Charged with first-degree murder, an all-white, all-male jury convicted each of the two white teens of 2nd degree manslaughter.

The two teens served one year each on probation.

For decades, Virgil Ware was largely ignored until a judge’s false claim about being his older brother made national headlines and rekindled interest in his tragic death.

Sims and Farley quietly apologized to his family, and Birmingham finally started to remember.

Virgil Ware: A teen who wanted a newspaper route

Virgil Ware lived in Sandusky, a neighborhood in northwest Birmingham. He was one of six children of James Ware, Sr., 40, an out-of-work coal miner previously employed at Tennessee Coal and Iron Steel Mill, and Lorene Ware, 36, who worked as a housekeeper.

He was in 7th grade at the all-Black Sandusky Elementary School, where he played football. His favorite tv show was Perry Mason and he aspired to be a lawyer like the show’s star, actor Raymond Burr.

Most mornings before school, Virgil Ware helped his Aunt Carrie Dowdell, 55, clean up the school building before classes started, the local press reported.

He sang in the church choir at St. Luke Baptist Missionary Church.

Virgil Ware and his oldest brother, James Ware, Jr., 16, went looking to purchase a used bicycle so that he could start a paper route with his older brother delivering The Birmingham News.

The two brothers left home early Sunday morning on September 15, 1963, riding double on James Ware Jr.’s bicycle.

World War II veteran, James “Jimmy” Grimmett, had invited the Ware brothers to his home in Docena, an old mining town west of Birmingham. Grimmett offered to take them to a scrapyard where the teens could look for a bicycle and spare bicycle parts.

Unaware of the bombing across town later that morning, they rode around all day, hoping to ride home on two bicycles.

White students & adults protesting the integration of West End High School in September 1963 / Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group.

White teens gather at the National States Rights Party rally

On the same day, Michael Farley, 16, and Larry Joe Sims, 16, who both lived in the Forestdale neighborhood in northwest Birmingham, attended a rally organized by the National States Rights Party (NSRP) at Dixie Speedway in Midfield, Alabama.

Farley and Sims were students at Phillips Academy, an all-white high school in Birmingham. They were Boy Scouts and had received the highest achievement in Boy Scouting, the Eagle Scout Award, for leadership, service and character.

The rally was one of many public demonstrations organized in Birmingham by the NSRP, a pro-segregation, white supremacist group. Since the beginning of September, NSRP held rallies to urge a white boycott of Birmingham schools. After years of advocacy led by civil rights leader Reverend Fred L. Shuttlesworth, integration of Birmingham’s schools had finally begun that month to implement the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v.s. Board.

Minor Heights Baptist Church Minister Farrell Griswold urged students at the rally to go home and avoid violence, according to press reports.

However, Griswold also encouraged students to ask their parents to sign permission slips provided by the West End Parents for Private Schools, Inc. to allow students to miss school the next day in a white boycott of school integration.

After the rally, Farley and Sims had planned to participate in a mass march against integration in Birmingham.

As organizers called off the march because of violence across the city after the church bombing, Farley and Sims went to the NSRP headquarters offices five miles south in Bessemer. Farley purchased a Confederate flag for 40 cents.

They hitched a ride home with their school classmate, Rodney Wallace, 16, according to his testimony later in court.

At around 4:00 pm, Farley and Sims boarded a red motor scooter, belonging to Farley’s parents. They rode around and ended up going west on Sandusky Road.

Farley’s newly purchased Confederate flag flapped in the wind on the back of the red motor scooter.

Sandusky Road sign. (Liz Ryan)

Black teens on a bicycle

“I will see you, Jughead,” said Virgil Ware around 4 pm on Sunday, September 15th.

He handed Grimmett $3 to give to a teen who was selling a used bicycle. Grimmett offered to bring the bike to the Wares’ house later.

The brothers left Grimmett’s house to head home. James Ware, Jr. steered with both hands and peddled. Virgil Ware sat on the handlebars holding on with both hands and resting each foot on the outside of the front wheel.

The Wares were going east on an open stretch of Sandusky Road when they heard an old car from behind them.

To avoid the car, James Ware Jr. steered the bike to the left side of the road.

The car followed them.

Peering out from the car windows, James Ware, Jr. and Virgil Ware saw two white teens they did not know, Clark Robbins, 18, and Ronnie Cork, 18.

Robbins and Cork drove past them, then stopped suddenly and started to back up the car in the direction of James Ware, Jr.’s bicycle.

Unsure of what the two white teens were up to, James Ware, Jr. turned the bike around and started riding in the opposite direction, away from home.

When James Ware, Jr. heard the car finally drive off, he turned the bike around to ride in the original direction, east towards home.

“We didn’t say anything to the boys in the old car and they didn’t say anything to us,” said James Ware, Jr. in a statement he later gave to the police.

Sandusky Road where Virgil Ware was shot. (Liz Ryan)

Shooting on Sandusky Road

Robbins and Cork kept driving east on Sandusky Road and encountered Farley and Sims riding towards them on the red motor scooter.

The teens stopped their vehicles for several minutes.

Robbins told Farley and Sims not to go further on Sandusky Road because there were two Black boys throwing rocks, according to a statement Robbins later gave to the police.

Farley opened his jacket. Robbins and Cork could see Farley’s .22 pistol in his belt.

Looking at the gun, Farley told them that he intended to use the gun to handle any encounter with the Black teens.

Farley handed the pistol to Sims.

Robbins and Cork drove away riding east.

Farley and Sims continued riding west on the red motor scooter.

A few minutes later, James Ware, Jr. and Virgil Ware were talking about their plans for the paper route when they heard a motor scooter coming towards them from the other direction.

As the red motor scooter got closer, James Ware, Jr. saw Farley and Sims, two white teens he did not know.

Even though James Ware Jr., Larry Joe Sims and Michael Farley were all 16 years old and lived within a few miles of each other, the teens did not know each other. They attended different schools because of Jim Crow segregation.

James Ware Jr. saw the driver, Farley, turn his head towards Sims, the teen on the back of the motor scooter, and say something that he could not hear, according to his statement to the police.

The teen on the back of the scooter, Sims, nodded his head up and down, appearing to agree with what the driver, Farley, had said to him.

A second later, Sims pulled out a .22 pistol.

Sims pulled the trigger. Then Sims pulled the trigger again.

Two blasts hit Virgil Ware in the chest and face.

Virgil Ware fell forward off the handlebars and into a ditch by the side of the road.

Black teen dies

“Get up Virge, you trimmin’ me,” said James Ware, Jr., according to the statement he later provided to the police.

“I can’t get up, I’m shot,” responded Virgil Ware.

“No, you’re not. You are going to have a heart attack like that,” James Ware Jr. said.

Virgil Ware didn’t respond.

Farley and Sims took off, leaving James Ware Jr. alone to fend for help for his brother, who was lying on the ground with two bullet wounds.

Five minutes later, a white couple in a green 55 Chevrolet stopped on the road to ask what happened.

Several other cars also stopped.

The driver in one car left to call the police, according to James Ware Jr.’s statement to the police.

When James Ware, Jr. saw blood on his brother’s teeth, he believed his brother was dead.

Virgil Ware died before the ambulance arrived to take him to the hospital, according to the coroner’s report.

Teen hides .22 pistol

Later that day, Robbins and Cork, driving around in their old car, encountered Farley and Sims for a second time on the red motor scooter.

Sims told them that he had shot one of the Black teens in the leg, according to the testimony Robbins later gave in court.

After that, Sims and Farley went to see Rodney Wallace.

They asked him to hide the .22 pistol.

Wallace went into the woods near his home. He dug a hole and put the pistol in and covered it with dirt.

He returned to his home, likely not realizing that he’d be called later to testify in court about it.

That same evening, Mountain Brook police officer, Paul Allen Couch, 28, heard on a police radio dispatch that Virgil Ware had been shot. Although he was off duty, Couch drove his car to the area where the shooting had taken place, and saw two white teens on a red scooter fitting the description on the dispatch. The scooter had a license plate M-5403 that belonged to an L.L. Farley.

Couch called Jefferson County police to share the information, according to press reports.

County police investigate

At 10:30 pm, Jefferson County Chief Deputy Raymond Earl Belcher, 42, spoke with police detective Edward Daniel “E. Dan” Jordan, 39, and assigned him to work the case with Detective James Alfred “Mac” McAlpine, Jr., 41.

“Dan, I hope you and Mac can solve the Ware case,” Belcher said, according to Jordan’s written account of the police investigation.

Jordan met up with Belcher, and the two detectives drove to the location where Virgil Ware was murdered.

It was too dark to examine the scene.

The two detectives arranged for a deputy police officer to inspect the scene the next morning.

White teen lies about his involvement

“Do you own a motorbike with the tag number M-5403?” asked Detective Jordan to the teen who answered the door the next day.

Detectives Jordan and McAlpine were at the home address provided to Jordan by police officer Paul Couch.

“Yes,” Michael Farley responded, according to Jordan’s written account of the police investigation.

Jordan continued to question Farley about whether he was riding it with another teen the day before.

“I was not riding my bike with anyone yesterday, I didn’t ride it either,” replied Farley.

After hearing Farley’s response, Jordan and McAlpine recognized that the teen had lied to them because Paul Couch had provided the tip that Farley and a friend had been on the scooter the day before.

The detectives decided to leave to gather more evidence.

Anonymous tipster provides lead

Detectives Jordan and McAlpine stopped for a quick bite at a local shop. After they purchased some snacks and walked outside, a grey-haired man walked out of the store behind them.

Jordan asked the man if he had heard anything about who had killed Virgil Ware.

The man said he did know and would only share information if he could remain anonymous.

Jordan agreed.

According to Jordan’s written account, the man told Jordan and McAlpine to check with the Wares’ insurance agent. The agent’s daughter was dating a young man who knew the two teens who’d killed Virgil Ware.

Although the tip sounded far-fetched, the detectives decided to follow up as they had little to work from at that point.

Jordan and McAlpine drove to the Wares’ house on Dekalb Street.

Mrs. Ware provided them with her insurance agent’s contact information.

Jordan called and spoke to the agent’s wife, who’d answered the phone. She gave him the name of the teen that their daughter was dating.

Jordan and McAlpine drove to the house of the teen, Clark Robbins. As no one was home, they left a note. The teen’s father, Jack Robbins, 52, called them back and agreed to meet up at the #78 Motel, 7 miles west of downtown Birmingham.

Clark Robbins brought his friend Ronnie Cork to speak to the detectives about their two encounters with Farley and Sims the day before.

The teens went to the Birmingham police precinct downtown and provided formal statements.

Teens confess

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” said Sims when Detective Jordan asked him what had happened the day before, on Sept. 15.

At Sims’ home with his parents present, Detective McAlpine told Sims that they’d spoken with Mike Farley and were aware that Sims shot Virgil Ware.

Sims then confessed that he’d shot Virgil Ware. He said he didn’t mean to kill anyone.

He began to cry. His parents did not say anything.

Jordan arrested Sims and put him in the back of the police car.

McAlpine and Jordan then drove to Farley’s house and brought Sims into the house.

With Farley and Sims facing each other, Farley looked at Sims and told him that he should not have confessed.

During the police interview, Farley told detectives that he’d purchased the .22 pistol for $15 from his friend Lester Hardin, 16, two days before the shooting, and that he’d asked his friend Rodney Wallace to hide the gun afterwards.

McAlpine and Jordan arrested the teens and drove to the Jefferson County jail.

Lt. David Orange, 32, of the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department, told reporters that Sims and Farley signed statements admitting that they killed Virgil Ware with a .22 caliber pistol.

“They didn’t give any reason,” said Orange. “They were very emotional and cried a lot,” he said.

Jefferson County Sheriff Melvin Bailey, 39, later told reporters that he had come up “with nothing that provoked the shooting.”

Police retrieve .22 pistol

Rodney Wallace answered the door when Detectives McAlpine and Jordan arrived at his home.

Aware that the pistol was no longer a secret, Wallace walked out of the house into the woods to show the detectives where he’d buried it.

Wallace removed the dirt over the gun and handed it to McAlpine.

The next day, McAlpine flew to DC with the pistol for an examination by the FBI.

The FBI conducted an analysis.

Two days later, the FBI sent a report to the Birmingham Police confirming that the two bullets from Virgil Ware’s body matched the .22 pistol.

Teens charged with first-degree murder

On September 20, the Jefferson County Circuit Court held a preliminary hearing on the case.

Under Alabama law, all 16 and 17-year-olds were automatically prosecuted as adults in circuit court prior to the Alabama Juvenile Court Act of 1975. The law subjected youth to placement in adult jails and prisons and adult sentencing, which could include execution for a murder case.

Sims and Farley sat at the defendants’ table handcuffed together.

Roderick Beddow, 74, a well-known criminal defense attorney, represented Sims. Nicknamed the Silver Fox, Beddow previously defended wrongfully accused, indigent clients in high-profile cases such as the Scottsboro boys, as well as white supremacists such as Ku Klux Klansmen. He served as the President of both the Birmingham and Alabama Bar Associations.

The courtroom was half full. About a dozen Black people attended, including Virgil Ware’s parents, James and Lorene Ware. Fifty white people were there as well. The parents of the defendants, Harrison Glendon Sims, 48, and Edith Sims, 49, as well as Louie Farley, 45, and Wynelle Farley, 42, attended.

No words were exchanged between the victims’ and defendants’ parents, according to press reports.

When asked to identify the two teens involved in the shooting, James Ware, Jr. pointed to Sims and Farley. The two white teens looked down at the defendants’ table rather than look at James Ware, Jr., news outlets reported.

During the hearing, Beddow never mentioned Virgil Ware by name, referring to him only as, “this colored boy.” Beddow could not remember or did not know the victim’s name, according to Mary McGrory, a columnist for The Washington Evening Star.

At the conclusion of the four-hour hearing, Jefferson County Circuit Court Judge Elias Calvin Watson, Jr., 53, announced that Sims and Farley would be denied bond and held pre-trial in jail.

Sims and Farley both sobbed when they heard the judge’s announcement.

However, that changed as a result of Sims and Farley’s attorneys filing a request with another judge to challenge the legality of their detention.

In a highly unusual decision in a murder case, Judge Wallace Clifton Gibson, 49, allowed Sims and Farley to be free on $10,000 bonds.

Harrison Glendon Sims, who worked as a manager at Sears, told news reporters that he did not understand the reason or motive for his son’s actions. He and his wife were not members of and did not attend meetings of segregationist groups. He had disallowed his son from attending.

“What Larry did was contrary to everything in [his] life and training,” he said.

Funeral held for Virgil Ware

“There should be no malice in anyone’s heart toward anyone else,” said Reverend J. R. Hicks to the more than 500 mourners attending the Noon service on Sunday, September 22, 1963 at St. Luke Baptist Missionary Church, as reported by news outlets.

“Virgil was a good boy. The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away,” he said.

Alabama state troopers with shotguns lined up along the road leading to the church appearing to be on hand to prevent any potential violence, according to published accounts.

Only two white people attended the funeral services, including Reverend Norman “Jim” Jimerson, 40, head of the Alabama Council on Human Relations.

During the services, mourners could hear “loud, sorrowful wails,” news sources reported.

After the services, the family arranged to bury Virgil Ware at Roberts Cemetery.

“They’re carrying my baby down the hill,” cried Lorene Ware as the hearse drove from the church down the steep hill on DeKalb Street on the way to the Roberts Cemetery, according to press reports.

Virgil Ware’s family laid him to rest in an unmarked grave a couple of miles from his home.

In solidarity with the Ware family and the other five families whose children were killed on September 15, 1963, thousands of people marched and prayed in cities around the country. Reportedly, New York and Washington, DC held the largest gatherings.

On the same day, the coroner signed Virgil Ware’s death certificate, indicating that he died of a massive hemorrhage from a bullet wound to the aorta and that his death was a homicide.

Grand jury indicts, white teens plead not guilty

On Friday, October 11, 1963, a Jefferson County grand jury indicted Farley and Sims on first-degree murder charges, according to Jefferson County District Attorney’s office records.

Even though they’d signed statements to police confessing that they’d shot and killed Virgil Ware, both Sims and Farley entered pleas of not guilty on November 1, 1963.

Trial starts, Self-defense argued

Judge Wallace Gibson started proceedings for Larry Joe Sims’ trial in Jefferson County Circuit Court on Monday, January 13, 1964.

The trial lasted all week.

Sims testified that his intent was to scare the two Black teens.

“I closed my eyes and fired at what I thought was the ground,” said Sims during his testimony. “I did not aim the pistol as I brought it out,” he said, according to news reports.

Deputy Coroner W.L. Allen testified that Virgil Ware died from a bullet wound to the chest that punctured his lung and severed the main artery in his heart. A second bullet hit Ware’s cheek and lodged in his jawbone.

“I believe I shot one of them in the leg. He fell,” said Clark Robbins in his testimony about what Sims told him after the shooting.

During the hearing, Judge Gibson made a remark to Sims and Farley about their lapse in judgment.

After hearing this, Virgil Ware’s mother, Lorene Ware, started to “break down in the courtroom crying and hollering,” recalled her son Melvin Ware in an interview with Time magazine.

In Beddow’s closing statements, he argued that Sims shot Virgil Ware in self-defense. He repeated Sim’s claim that Virgil Ware had thrown a rock at him.

The self-defense argument contradicted James Ware, Jr.’s statement to police that neither he nor his brother had rocks.

“They said we had rocks. We didn’t have anything,” said James Ware, Jr. in the book Foot Soldiers for Democracy: The Men, Women, and Children of the Birmingham Civil Rights Movement. “Virgil had both his hands on the handlebars, and it took all I could for pedaling, so we didn’t have anything,” he said.

In deputy solicitor Robert W. Gwin’s, 51, closing arguments for the prosecution, he called on the jury as the conscience of Birmingham and Alabama, according to press reports.

“If the race of the defendant and victim were reversed, you would not be in the jury room but a very short time before returning a verdict in one of the highest degrees of homicide in this case,” he said.

Guilty verdicts

In an uncommon move, the judge continued the trial proceedings into the weekend, on Saturday, January 18, 1964.

After the jury deliberated for nearly four hours, John D. Bullock, the jury’s foreman, read the verdict. The jury issued a guilty verdict of 2nd degree manslaughter.

Larry Joe Sims put his head down and started sobbing. Sim’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Harrison Glendon Sims, also broke down and sobbed, news outlets reported.

A few days later, Judge Gibson signed an order to imprison Sims for 7 months in the county jail to be followed by 2 years on probation, according to Jefferson County District Attorney’s office records.

On March 9, 1964, an all-white, all-male jury found Farley guilty of the same charge of 2nd degree manslaughter and also sentenced him to 7 months in the county jail and two years’ probation, according to Jefferson County District Attorney’s office records.

However, Judge Gibson suspended Sims and Farley’s sentences at the county jail and retained their terms of probation, according to a U.S. Department of Justice memo.

The following year, Judge Gibson reduced their probation from two years to one year.

Their terms of the teens’ probation concluded on June 29, 1965, which coincided with their graduation from high school.

Both Sims and Farley finished high school.

Legal fallout

“The verdict wasn’t right,” says James Ware, Jr. in Footsoldiers for Democracy. “I figured that they would have gotten way more than what they did for what they did.”

Melva Jimerson, 40, wife of Reverend Norman “Jim” Jimerson, attended one of the days of the trials to show her concerns and support for the Ware family.

“This was not something she would normally do,” says her son Randall Jimerson in a telephone interview from his home in Washington State in May 2025. “There was a real sense of injustice about the trial,” he said.

Criminal justice experts assert that the sentences would have resulted in significant prison time, and possibly execution, if the defendants were Black and the victim was white.

“No question if the situation had been reversed, the Black youth, if still alive, would be in jail,” says former Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley in a telephone interview from his law offices in Vestavia Hills, Alabama, in April 2025. “In my mind, they would have been treated differently,” he said.

Judge’s false claim rekindles case

For more than thirty years, Virgil Ware’s death went unnoticed until a 1997 article in the Birmingham News. The family of Virgil Ware disputed a judge’s claim that he was Virgil Ware’s older brother James. The judge asserted that his younger brother’s death was what motivated him to seek justice. His name was also James Ware, and he was from Birmingham.

With the false claim exposed, Judge James Ware asked President Clinton to withdraw his nomination for a federal appeals judgeship in California.

Birmingham attorney Mark White represented the Ware family and handled the media calls during this period.

“The demand to talk with James Ware, Jr. was overwhelming,” says White in an interview in his law offices in April 2025.

White brokered a meeting with Judge Ware and Virgil Ware’s family, where the judge could apologize.

“The meeting was compelling on both sides,” says White.

All of the publicity about the judge’s false claim prompted Michael Farley to contact the Ware family to apologize for his role in the murder.

“I was shocked when that guy called to apologize,” said James Ware, Jr. in Footsoldiers for Democracy. “I went on and accepted the apology because you can’t go around hating the world. Let the lord take care of that.”

Candias Wilson, 54, James Ware, Jr’s daughter, first learned as a teenager about her uncle’s murder when press reports about the judge’s false claim surfaced and she spoke with her father about it.

“He never wanted to talk about it. He was actually there when it happened and my uncle died in his arms,” says Candias Wilson in a telephone interview from her home in Birmingham in April, 2025.

“He thought that one of the bullets was supposed to be for him,” she said.

Grave site moved, headstone placed

Candias Wilson says that her Dad told her several times that, “If I ever hit the lottery, one of the first things I’m going to do is have my brother’s body exhumed from where it’s at.”

After readers of Time magazine donated funds in response to a 2003 article about Virgil Ware, the Ware family arranged to exhume him from the unmarked grave at Roberts Cemetery and reinter him at the George Washington Carver Memorial Gardens.

They placed him next to his mother, Lorene Ware, who had passed away in 1996. A new headstone was placed on the grave.

The reporting on the 2003 Time magazine article spurred Sims to also contact the Ware family to quietly apologize.

FBI opens, closes case

The FBI opened Virgil Ware’s case on February 20, 2009, under the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Act (P.L. 110-344). Signed into law on October 7, 2008, by President George W. Bush, the law required the FBI to investigate civil rights crimes that resulted in a death before December 31, 1969.

During the FBI’s investigation, they were unable to locate court transcripts or local investigative reports.

The U.S. Department of Justice memo on the case indicates that they contacted the Jefferson County family court and were advised that the youths were likely prosecuted in juvenile court and that the state trial transcripts were likely destroyed years before.

However, Sims and Farley were prosecuted in circuit court. Before 1975, Alabama law required that all 16 and and 17-year-olds be processed in circuit, not family court.

The case was only open for two months before the FBI closed it on April 22, 2009, stating that “the subjects were already prosecuted for this matter.”

According to a U.S. Department of Justice memo, the FBI contacted Ware family members who “did not want to speak to the agents about the victim’s death because they considered the matter completed.”

Birmingham remembers Virgil Ware

Birmingham has begun to take more visible steps to recognize Virgil Ware, especially in the past decade and a half.

The City Council placed a plaque for Virgil Ware in the city’s Gallery of Distinguished Citizens in Birmingham’s City Hall in 2011.

Birmingham also placed two markers in memory of Virgil Ware, one across the street from where he lived on DeKalb Street and one at the bottom of the hill on the corner of DeKalb Street and Cordova Avenue.

On the 50th anniversary of the church bombing, Birmingham unveiled Four Spirits, the first large-scale public sculpture about the lives that were lost. The sculpture is in Kelly Ingram Park diagonally across from the 16th Street Baptist Church.

Created by world-renowned sculptor Elizabeth MacQueen, Four Spirits incorporates four figurines of the girls and doves representing the impacted children, including Virgil Ware, along with photos of each.

During her childhood in Mountain Brook, a city east of Birmingham, MacQueen had not heard about Virgil Ware’s murder. MacQueen felt that it was very important to include Virgil Ware and Johnnie Robinson along with the four girls who were killed in the sculpture.

“It’s time that they were honored,” says MacQueen in a telephone interview from Paris, France, in May 2025. “I looked up their stories and decided to put their names on the bench.”

After seeing Four Spirits, MacQueen hopes that people walk away with a very strong message.

“I want people to say no more. Stop killing children,” she said.

Next to Kelly Ingram Park, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (BCRI) houses a permanent exhibition about the children who were killed on September 15, 1963, including Virgil Ware.

One of BCRI’s public outreach and education programs, Beyond King, brings together Jefferson County high school students who meet weekly for 13 weeks to learn about all the institute’s exhibitions. The students then create presentations about people who have been forgotten, such as Virgil Ware. After the program concludes, the students share their presentations with their classmates.

“Every Tuesday night I’m here with a group of 25-30 young people to work with them to change the world,” says BCRI historian Barry Neely, 55, who has worked at the institute for more than thirty years. “Enough people have died already that we can find our way to justice without anyone else being killed,” he said.

Virgil Ware’s family continues to ensure he is remembered.

Candias Wilson works in the hotel industry in Birmingham and meets visitors to the city every day as part of her job.

“I always tell visitors to go to the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute,” says Candias Wilson. “I tell them that I know someone there, my Dad’s brother,” she said.