The Institute for Justice has filed a lawsuit on behalf of three Alabamians challenging the constitutionality of warrantless searches by state game wardens. The case, filed under the Alabama Constitution, asserts that game wardens routinely violate property owners’ rights by entering and surveilling private land, often marked with “no trespassing” signs, without a warrant or probable cause.

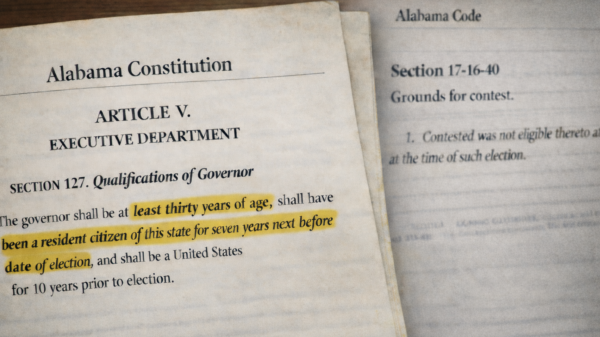

The lawsuit is part of IJ’s broad effort to dismantle the “open fields doctrine,” a century-old U.S. Supreme Court ruling that the federal Fourth Amendment does not protect undeveloped private land from warrantless searches. This doctrine still governs federal officials, but seven states have already rejected it under their constitutions. IJ hopes to make Alabama the next.

The plaintiffs in this case include Dalton Boley, Dale Liles and Regina Williams. All three have repeatedly had their land entered and searched by Alabama game wardens without permission, warrants or prior notice.

IJ attorneys Josh Windham and Suranjan Sen are leading the charge in court.

“The Alabama Constitution makes it clear that if the government wants to come searching on your property, they need a warrant based on probable cause, and game wardens are not exempt from the Constitution,” Sen said. “They’re allowed to ignore ‘no trespassing’ signs. They’re allowed to hop fences. They’re allowed to rummage around in your backyard without your permission, without your knowledge and without a warrant.”

“This used to be a place where I could come to relax and get away from it all, but now that I know someone could be snooping around, I find it hard to just go there and relax,” Boley said.

At the heart of the lawsuit is an Alabama statute that allows game wardens to “enter upon any land … in the performance of their duty.” IJ argues that this law violates the Alabama Constitution’s protections against unreasonable searches and seizures. The Institute is seeking a ruling that affirms that private land, whether used for hunting or recreation, deserves the same constitutional protections as the home itself.

Windham explained that while federal law allows such intrusions, states can provide greater protection for individual rights, and many already do.

“Private property is supposed to be private,” said Windham. “In Alabama, the Constitution guarantees that privacy. We’re asking the courts to enforce that promise.”

Recently, IJ has launched similar challenges in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Louisiana and Tennessee. The Tennessee case, Rainwaters v. Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, ended in a state court striking down warrantless surveillance on private land.