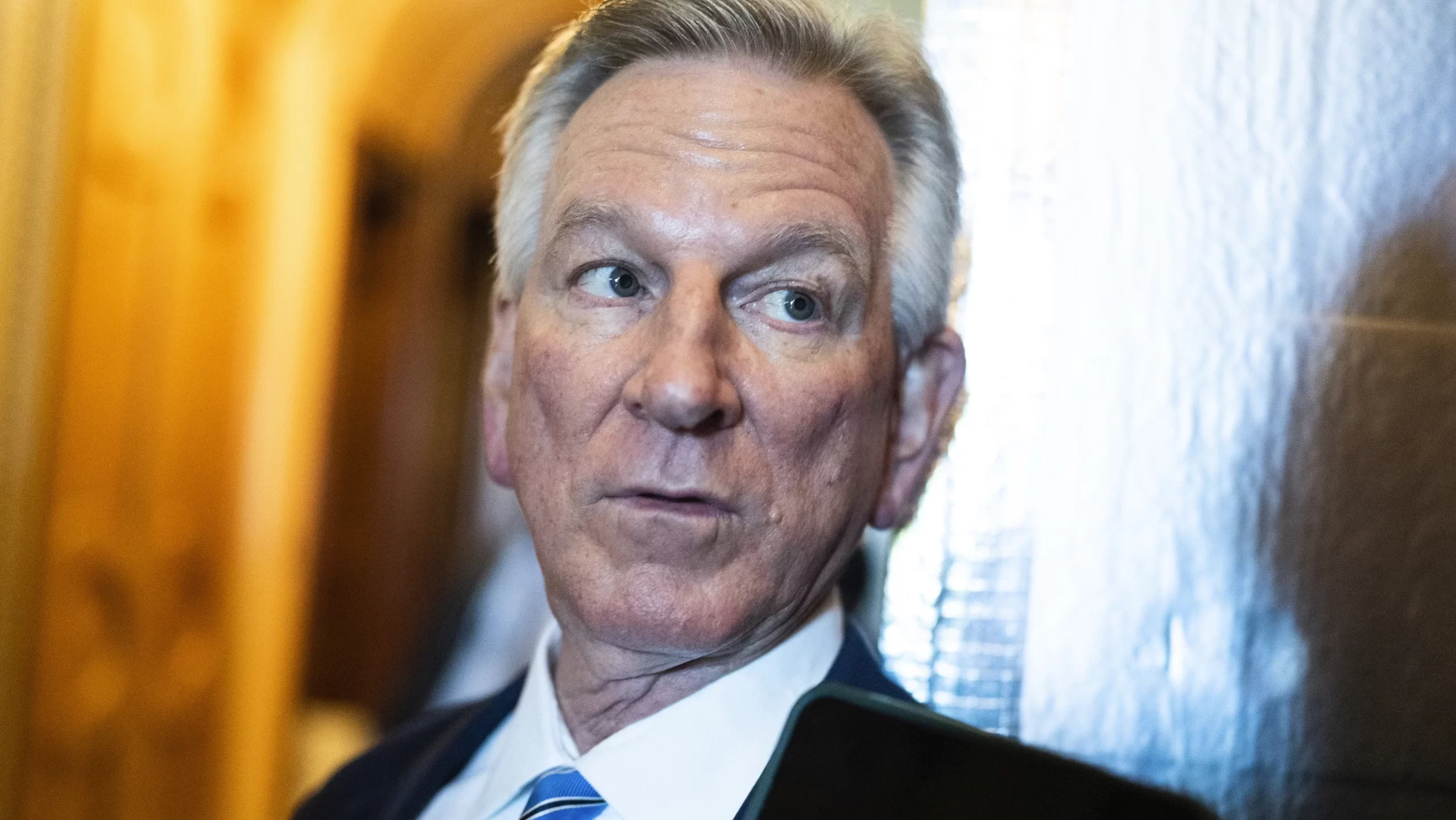

Senator Tommy Tuberville wants you to know he doesn’t think Alabama should have to pay hundreds of millions of dollars in order to keep the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program running.

Formerly known as food stamps, today SNAP helps 1 in 7 Alabamians afford their groceries. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act passed by the House last month would require state governments to cover a share of SNAP benefit costs for the first time ever. The federal share of administrative costs would also be cut in half from 50 percent to a quarter.

According to estimates by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and the Center for American Progress, the House bill would cost Alabama north of $119 million in the 2026 fiscal year alone and possibly far, far more than that because of some ridiculously punitive quality control incentives.

Earlier this month, Tuberville told Politico “everybody that’s going to be in state government is going to be concerned about it.” A bit understated perhaps, but I fully agree with the senator.

“I don’t know whether we can afford it or not,” he matter-of-factly stated. Several anonymous Republicans also told the outlet Tuberville had actually been lobbying Senate leadership behind the scenes to adjust the proposal.

And a week ago, Tuberville said those talks had been “real good” and “better than expected” according to the Alabama Daily News.

Credit where credit is due, Alabama’s senators and representatives really ought to be fighting cuts to the social programs helping hundreds of thousands of Alabamians pay their bills.

I just have two questions: When did Tuberville start caring about SNAP? And did those talks actually change anything?

Back in 2021, the Biden administration utilized a clause in the 2018 Farm Bill to raise the price of the Thrifty Food Plan by $1.20 per person per day, or around 21 percent. Because the TFP is used to calculate the value of SNAP benefits, Urban Institute researcher Laura Wheaton estimated this adjustment by itself decreased poverty in Alabama by 8.1 percent.

From his seat on the Senate agricultural committee though, Tuberville has spent the past few years describing reevaluating the TFP as the height of fiscal irresponsibility, an abject waste of money that would have been better spent on more subsidies for farmers.

Just this past January, Tuberville attacked the increase in spending on SNAP as “over the top” and called the adjustment a “massive increase in the TFP.” When Democrats put together a Farm Bill proposal in 2024, he explained he opposed the proposal because it “prioritizes spending on nutrition and conservation instead of farm programs.”

Even more recently, while questioning Trump’s nominees to lead the Department of Agriculture this past April, Tuberville griped that the reevaluation discouraged people from working and said “we can’t help everybody just because they don’t wanna do anything.”

Again, I cannot stress enough that reevaluating the TFP increased SNAP benefits by a whopping $1.20 per person per day. Forty cents a meal.

Now, having laid out Tuberville’s statements on SNAP over these past few years, I’m not so convinced he’s adequately concerned about the over 750,000 Alabamians who need SNAP to buy food every month.

What I do believe is that Tuberville’s pretty sure he’s going to be elected governor next year and doesn’t want to be stuck with a $119 million bill he’ll have to figure out how to pay. So he decided he could try actually legislating for a week to make his life in Montgomery a tad easier.

Well, after Tuberville’s purported work behind the scenes, the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry released its budget reconciliation proposal last week. How much might Governor Tuberville still have to find in the state coffers after all those “real good” talks?

In a phone call yesterday, Alabama Arise senior policy analyst Carol Gundlach explained to me that the Senate proposal is “so minisculely better that it doesn’t make any difference.”

“It’s going to do exactly the same thing. It’s going to cut people off of SNAP; it’s going to cut people with young children off of SNAP who cannot jump through the hoops; and it’s going to cost the state a whole bunch of money,” Gundlach said. “We are very disappointed in the Senate because we had thought that they would fix some of this, and they have clearly not.”

The Senate version does lack the baseline 5 percent SNAP benefit cost share found in the House version, but would still make states pay a share of SNAP benefit costs as penalties for high payment error rates. (Payment error rates are the rate of both over and under payments and are meant to “measure the accuracy of each state’s eligibility and benefit determinations,” not the level of fraud.)

If the “quality control incentives” went into effect this year and Alabama happened to still have the same payment error rate it did in the 2023 fiscal year, the state would be charged over $80 million.

Gundlach also pointed out to me that the Senate version of the bill would make it harder for veterans, homeless people, and people aging out of foster care to receive SNAP benefits.

Under both existing law and the House proposal, those groups are exempt from the stricter work requirements placed on “able-bodied adults without dependents,” or ABAWDs. But the Senate proposal removes all three from the list of excused groups, in addition to increasing the upper age limit for ABAWD status by ten years and requiring dependents be under 10 years old.

If the Senate’s budget is signed into law, the state of Alabama will still be stuck with the bill. And veterans across the country will be more likely to go hungry.

Tuberville’s campaign did not respond to an email I sent yesterday asking how he’d work to replace lost federal funding for SNAP if elected governor. But if the Senate’s proposal for SNAP is what happens when Tuberville actually tries to deliver for the people of Alabama, I’m sure not optimistic about the decisions he’d make in Montgomery.