There is a problem with the United States Supreme Court.

A big problem.

A problem that goes far, far beyond its conservative slant and its penchant for setting aside decades of precedent (including this current court’s own precedent) to bend to the whims of today’s conservative wants. A problem that should trouble every single American, particularly the lawyers among us, regardless of political ideology.

America’s highest court is not issuing opinions.

To put that another way: It is not justifying its decisions on paper and providing the country, and the legal world, its reasoning – no matter how sound or flimsy it might be – for the monumental (in some cases) decisions that it is making.

Perhaps the biggest and most consequential example of this came Monday, when the Roberts court lifted a lower court’s stay and allowed the Trump administration to move forward with the dismantling of the U.S. Department of Education.

Justice Sotomayor, writing a dissenting opinion for the three liberal justices, briefly explained their reasons for dissenting.

No one from the conservative majority offered a word of explanation.

Let’s put that in perspective for a moment, and forget the partisan back and forth that goes with basically any SCOTUS decision these days. This is an issue of function, not of ideology.

The U.S. Department of Education was created by an Act of Congress in 1979 and properly signed into law by then-President Jimmy Carter. Each year, Congress appropriates the funding of the department and its various initiatives and programs.

Congress can, at any time, abolish that act, rewrite it, change it or modify it. It can fire every employee at the department. It can completely defund the entire department or change completely the way the money is spent by the department.

But you know who can’t do any of that?

The President of the United States.

According to the “Take Care” clause of the Constitution, it is the president’s duty – DUTY – to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” That means it is the president’s responsibility to ensure the wishes of Congress are done.

Donald Trump has done the opposite. And his efforts to abolish the DOE quite clearly run afoul of the “Take Care” clause.

But even if you believe, due to some technicalities or your interpretation of the laws and his actions, that he has not run afoul of that clause, I believe that we can at least agree that there is a strong argument that he has. An argument that can be made in good faith. An argument that should be heard and considered by a court of law. An argument that must be weighed in the context of the guidance of the Constitution.

Well, two lower courts heard that argument and agreed that Trump’s actions in seeking to fire some 1,400 DOE employees – along with his public statements in which he flatly claimed that it was his intent to abolish the DOE – constituted an illegal act unless he first received approval from Congress.

Such approval would never come, not even with Republicans in control of both houses. Because those lawmakers know what we know – the federal government’s management of schools, and its guarantee of federal programs that aid underprivileged children, are the only things allowing many rural schools in red states to function. And those lawmakers know that should that funding go away – as it likely will – and those schools falter, there will be a steep, steep political price – not to mention an ethical one – to pay with voters at home.

But even if you’re willing to dismiss or overlook all of that, the one thing we should absolutely agree on is that a court either allowing or denying a president the right to do all that Trump is doing should offer an explanation. It should be parsed. The opinion of the court should be clear.

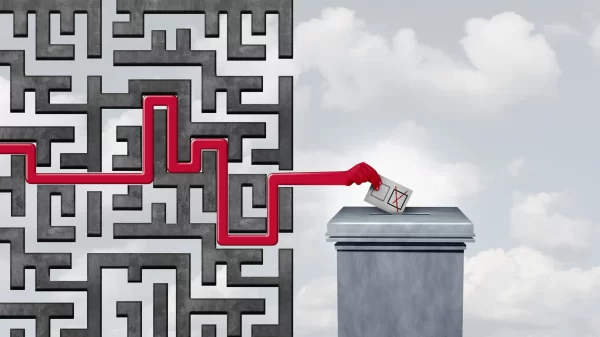

It should not come from the “shadow docket,” where emergency petitions are decided. The highest court should not arbitrarily lift stays and allow questionable acts to continue without explanation, particularly when reversing a lower court that sought to delay what it deemed harmful or potentially illegal actions.

We don’t have kings around here. And it’s the judiciary’s responsibility to ensure that the one position in our government that comes closest – the president – remains firmly within the confines of our constitutional laws.

So, if you’re going to shirk that duty, you should at least explain yourself.